With Love Yourself: Answer, the curtain finally falls on BTS’ two-year-long Love Yourself series. We’ve reviewed each of the MVs and albums, so it’s time to take a step back to mull over the series as a whole. What did it promise, how was it executed, and did it deliver on its promises? It’s an ambitious project, with an unconventional angle on the familiar theme of love. Adopting the common narrative structure of exposition, conflict, and resolution, it sought to express the idea that in order to love someone else, you have to learn to love yourself.

With Love Yourself: Answer, the curtain finally falls on BTS’ two-year-long Love Yourself series. We’ve reviewed each of the MVs and albums, so it’s time to take a step back to mull over the series as a whole. What did it promise, how was it executed, and did it deliver on its promises? It’s an ambitious project, with an unconventional angle on the familiar theme of love. Adopting the common narrative structure of exposition, conflict, and resolution, it sought to express the idea that in order to love someone else, you have to learn to love yourself.

Each comeback is tied to a part of this structure. Love Yourself: Her, the exposition helmed by “DNA”, focuses on different experiences of first love. Tear and “Fake Love” develops the conflict: the darker sides of love. Finally, Answer and “Idol” portray the outcome of the struggles explored in Tear. Romantic love has been the subject of countless songs and MVs, making Her familiar ground. But Love Yourself’s true potential lies in Tear and Answer’s themes of self-love and self-discovery, and in the idea of reconciling the different identities we construct or hide, to earn the affection and respect of others.

Despite its rich potential, however, Love Yourself ultimately fails to deliver the emotional payoff latent in its premise. The problem lies not in the plan, but the execution. K-pop releases sometimes suffer from a lack of inspiration, but Love Yourself is plagued by the opposite. It is filled with too many ideas and swings between different artistic approaches. As a result, it lacks stylistic and thematic coherence. Paired with the fatal choice to link the series back to the storyworld of The Most Beautiful Moment in Life (HYYH), Love Yourself never got the chance to fully flesh out its message or story the way previous comebacks did.

Despite its rich potential, however, Love Yourself ultimately fails to deliver the emotional payoff latent in its premise. The problem lies not in the plan, but the execution. K-pop releases sometimes suffer from a lack of inspiration, but Love Yourself is plagued by the opposite. It is filled with too many ideas and swings between different artistic approaches. As a result, it lacks stylistic and thematic coherence. Paired with the fatal choice to link the series back to the storyworld of The Most Beautiful Moment in Life (HYYH), Love Yourself never got the chance to fully flesh out its message or story the way previous comebacks did.

To be sure, diversity of form and content does not always lead to a lack of coherence in BTS’ material. The Wings short films had different looks and elements, chosen to bring out a story specific to each member. They were also aesthetically different from the “Blood Sweat & Tears” MV. Yet the videos are identifiable as part of the same series. They are tied together by a dramatic atmosphere and an undercurrent, or overtones, of darkness, whether visual or emotional.

BTS’ creative team are no strangers to a nuanced layering of artistic approaches or thematic ideas either. HYYH owed its artistic excellence in part to how narrative elements melded organically with symbolic touches, which I’ve discussed in a previous article. The Wings videos deftly wove together the central idea of a boy encountering temptation with themes of artistic growth, and the personal struggles of each member.

BTS’ creative team are no strangers to a nuanced layering of artistic approaches or thematic ideas either. HYYH owed its artistic excellence in part to how narrative elements melded organically with symbolic touches, which I’ve discussed in a previous article. The Wings videos deftly wove together the central idea of a boy encountering temptation with themes of artistic growth, and the personal struggles of each member.

Love Yourself, however, splays frustratingly in too many directions. Each of these directions are intriguing on their own. But put together, they emphasise the creative team’s failure to commit to one artistic vision that would unite the separate threads of the series. The problem is twofold. In the execution of the theme, there is an awkward mix between a universal narrative and a specific one. Stylistically, Love Yourself is an odd chimera of aesthetics, symbolism, a lot of choreography shots, and most disappointingly, mere glimpses of an incompletely developed narrative.

Thematically, the creative team was unable to decide if Love Yourself’s story should be a fictional narrative arc more relatable to different audiences, or anchored in a biographical angle, portraying BTS’ struggle with the gap between their identities as an idol and artist, and their other selves. Their choice to keep both approaches is understandable. HYYH’s fictional story had a universal appeal but wasn’t specific to the BTS’ own experiences. Wings’ stories were solidly rooted in their experiences but weren’t necessarily relatable to their audience and fans. Love Yourself offered the perfect opportunity to balance both.

The problem, however, is that Love Yourself doesn’t weave the two narrative threads together and develop them throughout the series. It keeps them separate and doesn’t expand properly on either. The resulting fragments don’t fit together to tell the story in a continuous way. “Highlight Reel” goes in for a fictional story arc, recalling HYYH’s approach. It is rich in possibilities for the theme. “I was afraid. I had no confidence that I could be loved for who I am,” Jin narrates poignantly, and we see hints of the broken friendships and romances caused by this lack of self-love. There are also intriguing glimpses into psychosocial reasons for such a complex. This is especially evident in the possible backstory for J-Hope’s character, who was abandoned by his mother at an amusement park. It’s a traumatic circumstance that could cause a child to develop a lifelong struggle with his sense of self-worth.

It’s baffling, then, that Love Yourself cast aside such a compelling setup in subsequent comebacks. Perhaps the reception to the trailer was unfavourable, or there was simply a push towards a more universal approach. No traces of the “Highlight Reel” story and characters can be found in “DNA”, which opted for an abstract representation of the experience of falling in love. It works fine as a very well-styled, big-budget dance MV, but it was anticlimactic after the expectations set up by “Highlight Reel”. Without specific links to the theme of Love Yourself, it could easily be a standalone MV about the thrills of falling in love, rather than a distinct part of the series.

It’s baffling, then, that Love Yourself cast aside such a compelling setup in subsequent comebacks. Perhaps the reception to the trailer was unfavourable, or there was simply a push towards a more universal approach. No traces of the “Highlight Reel” story and characters can be found in “DNA”, which opted for an abstract representation of the experience of falling in love. It works fine as a very well-styled, big-budget dance MV, but it was anticlimactic after the expectations set up by “Highlight Reel”. Without specific links to the theme of Love Yourself, it could easily be a standalone MV about the thrills of falling in love, rather than a distinct part of the series.

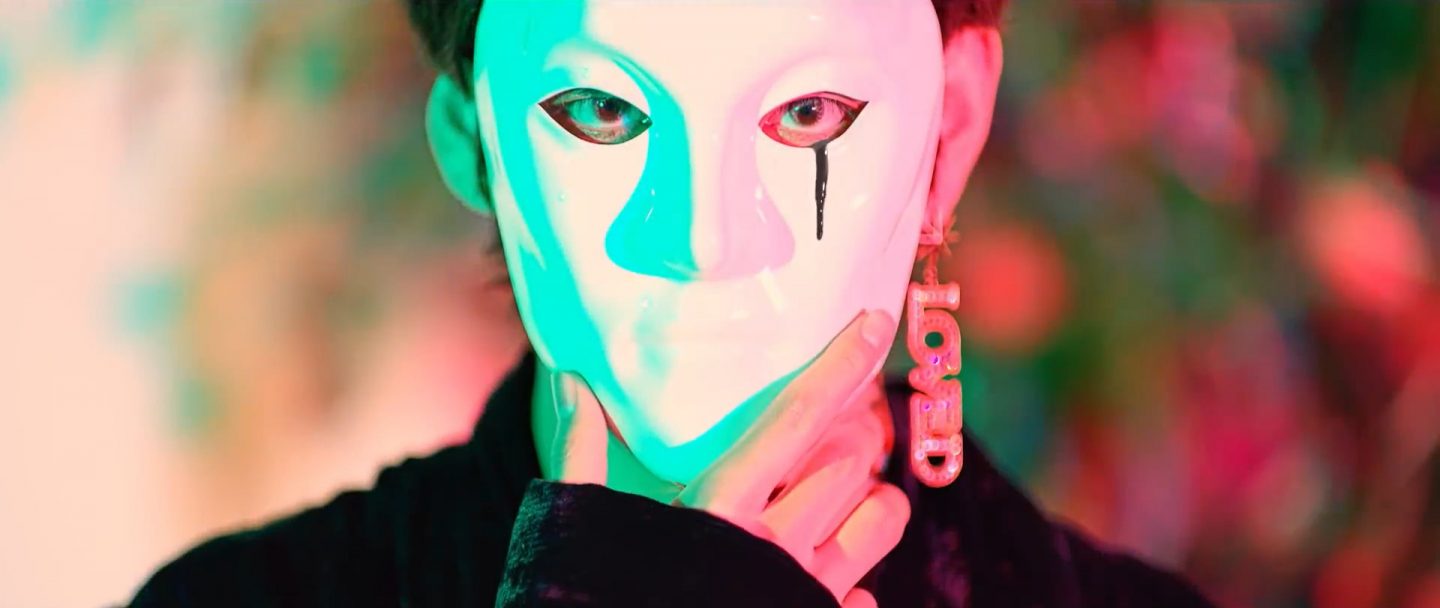

The weakest link, though, is really in “Fake Love”. It suffers from promising ideas that were never fleshed out. In the teaser, the process of working through a psychological struggle is externalised, portrayed as the act of trading an item at a magic shop. It also introduced the motif of masks, which symbolises a false identity used to cover one’s true self. But neither of these ideas were expanded on in the actual MV; the mask motif was tacked on at the very end of the extended version of the MV.

The bulk of the MV draws instead from references to motifs in past comebacks. It’s one thing for references to be Easter eggs for fans, allowing them a deeper understanding of the meaning of the MV. But it’s another thing to rely completely on these references to give meaning to the MV. To the viewer unfamiliar with HYYH and Wings, the members’ individual sets make no sense, and “Fake Love” would just be a very grandiose dance MV. If the deliberate shift away from specificity in “Highlight Reel” to abstraction in “DNA” and “Fake Love” indicates a desire to increase the relatability of the series, this artistic decision makes very little sense. Viewers can’t relate to something they don’t understand.

Each of the past eras had distinct images. HYYH had cherry blossoms and lilies, fire, water, running; Wings had apples, chocolate, paintings and sculptures, and mirrors. Even “Spring Day”, which wasn’t strictly part of either series, had recognisable symbols chosen specifically for it: washing machines, laundry piles, a pair of white canvas shoes, a carousel. The rehashing of visual elements from these past eras deprives Love Yourself of the chance to properly develop its own set of motifs. It is never given the room to focus on its unique symbols, such as masks or the smeraldo flower, because the meaning of the borrowed imagery is already assumed to be understood.

Each of the past eras had distinct images. HYYH had cherry blossoms and lilies, fire, water, running; Wings had apples, chocolate, paintings and sculptures, and mirrors. Even “Spring Day”, which wasn’t strictly part of either series, had recognisable symbols chosen specifically for it: washing machines, laundry piles, a pair of white canvas shoes, a carousel. The rehashing of visual elements from these past eras deprives Love Yourself of the chance to properly develop its own set of motifs. It is never given the room to focus on its unique symbols, such as masks or the smeraldo flower, because the meaning of the borrowed imagery is already assumed to be understood.

Like “DNA”, then, “Fake Love” is visually dense, but conceptually spare. As the “conflict” stage in the narrative structure, it is even more pivotal to the story arc than “DNA”. No amount of aesthetic grandeur can mask its lack of substance and emotional punch. Consequently, “Idol” arrives as a very jarring resolution. It’s not just a very loud, explosive conclusion to a poorly developed struggle. It’s not even an answer that matches the vague narrative of “DNA” and “Fake Love”.

“Idol” resolves a struggle that’s very specific to BTS, one in which they confront the tension between their public image and their more vulnerable, imperfect selves. In “Idol”, BTS present their answer: they don’t have to choose between their multiple identities; they can just learn to embrace all of them. But in an attempt to keep things universally relatable, neither “DNA” nor “Fake Love” had details related to this specific struggle. When considered together with “Highlight Reel”, the split in approach becomes even more stark.

“Idol” resolves a struggle that’s very specific to BTS, one in which they confront the tension between their public image and their more vulnerable, imperfect selves. In “Idol”, BTS present their answer: they don’t have to choose between their multiple identities; they can just learn to embrace all of them. But in an attempt to keep things universally relatable, neither “DNA” nor “Fake Love” had details related to this specific struggle. When considered together with “Highlight Reel”, the split in approach becomes even more stark.

The greatest pity about the way Love Yourself panned out is that it actually has everything it needed to excel. You don’t need to look further than “Highlight Reel” and the comeback trailers to see two possible directions that could’ve worked coherently, with a greater emotional payoff. One option would have been to commit to the fictional narrative in “Euphoria” and “Highlight Reel”. The main MVs could have focused on developing the story, instead of flitting between choreography shots and other scenes that bring in a host of under-developed ideas. The narrative doesn’t have to be conveyed straight up either. The treatment of the narrative could take a leaf out of “I Need U”, “Run” or “Spring Day”, incorporating interesting film techniques or subtle symbolism.

“Serendipity”, “Singularity”, and “Epiphany” share a symbolic, mood-focused approach. Though short, each trailer clearly expressed a core emotion: the wonder of falling in love (“Serendipity”), haunting self-doubt (“Singularity”), and the feeling of entrapment accompanied by dim hope (“Epiphany”). It’s also evident from these trailers that the series doesn’t need a literal narrative, or links back to HYYH, to achieve emotional depth. The title track MVs could have consistently adopted this style, bringing out the emotional nuances of the narrative through more stylised ways.

Considered in isolation, each of the three MVs are decent efforts, especially “Idol” with its imaginative infusion of traditional cultural elements with a campy, safari-on-drugs look. But considered in the context of the Love Yourself series, they fall short. The mishmash of styles and thematic foci ultimately exposes the hasty planning process, with new details and directions being thrown in along the way.

Considered in isolation, each of the three MVs are decent efforts, especially “Idol” with its imaginative infusion of traditional cultural elements with a campy, safari-on-drugs look. But considered in the context of the Love Yourself series, they fall short. The mishmash of styles and thematic foci ultimately exposes the hasty planning process, with new details and directions being thrown in along the way.

The decision to force links to other series also makes the process of working out the narrative exhausting. The open-endedness of HYYH was rewarding to mull over because the uncertainty created was central to the theme of youth and growing pains. The same complexity does not, however, map well onto Love Yourself. Because Love Yourself never quite figured out what it wanted to be, this complexity only obscures its message further, rather than driving it home.

There’s no doubt that Love Yourself coincides with the most commercially successful period of BTS’ career thus far. But it’s increasingly difficult to ignore signs that what Big Hit and BTS have worked so hard to earn is also stretching them thin artistically. It’s a dangerous place to be, especially considering how these current successes were built on the artistic excellence of earlier projects. Moving forward, it seems that what Big Hit and BTS need is to slow down to reflect on the shortcomings of their more recent efforts. They need to learn how to extrapolate from past approaches, but also make a clean break from earlier material, rather than attempt to build up an increasingly inaccessible BTS universe that prioritises form over content.

(YouTube [1] [2]. Billboard, Joy News 24. Images via Big Hit Entertainment.)