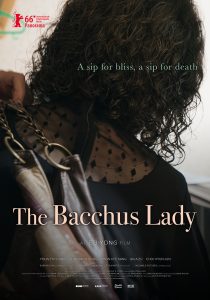

A world of Bacchus drinks, assisted euthanasia, and the unforgivable reality of old age, is what director E J-young creates with his latest film project “The Bacchus Lady.” Released in 2016, this comparatively low budget film encompasses hard truths that deal with the elderly population in South Korea and their struggle to be seen and recognized as worthy members of society from a country they once helped flourish. Focusing in on just one story of many, The Bacchus Lady shows the grim but realistic life of one elderly woman who survives by selling sex daily to the elderly men that wander around Seoul’s Jongno Park.

A world of Bacchus drinks, assisted euthanasia, and the unforgivable reality of old age, is what director E J-young creates with his latest film project “The Bacchus Lady.” Released in 2016, this comparatively low budget film encompasses hard truths that deal with the elderly population in South Korea and their struggle to be seen and recognized as worthy members of society from a country they once helped flourish. Focusing in on just one story of many, The Bacchus Lady shows the grim but realistic life of one elderly woman who survives by selling sex daily to the elderly men that wander around Seoul’s Jongno Park.

Once a friendly family spot, Jongno Park is now the main job location of more than 400 prostitute grandmothers nicknamed ‘Bacchus Ladies.’ The term ‘Bacchus Lady’ has become the staple name in defining prostitute grandmothers from Korea. Although once known exclusively as an energy drink, the bottled refreshment has taken up a secondary meaning that ensnares the shame and contempt for the women’s work, but their greater need for survival eclipses the guilt.

In her boldest role yet, veteran actress Youn Yuh-jung plays the feisty female protagonist, So-young. Having come to terms with the way her life has turned out, So-young proudly strides the park with a bottle of Bacchus in her purse to offer men as an innuendo for sex. Despite having the the world’s 11th largest economy, South Korea has 65% of its elderly citizens living below the poverty line, the biggest among all OECD countries. And being one of the 65% Korean elders, So-young and many other women have had no choice but to sell themselves for a living.

One Bacchus lady can make as much as 30,000 won ($17) for any given day, occasionally giving discounts to their regular customers. And although most are weary about the police, patrol cops who routinely make their rounds around public parks are rarely able to make an arrest; privately stating that the prostitution problem will never be solved by spontaneous crackdowns, that senior citizens need an outlet for their sexual desire and comfort from loneliness and ultimately it is the policy that needs to change.

Nicknamed “The forgotten generation” Korea’s elder population are seen as victims of their own country’s success. Similar to the main character, many elders drifting past retirement have invested their youth and their earnings into generating the economic powerhouse Korea is today, but most — if not all — were compensated back with empty hands.

So-young’s now withered youth — before she became a Bacchus Lady — represents a time in Korean history where there was no need to worry about the fate of the aging population. In a country where Confucius ideals once reigned, children in Korea traditionally had the responsibility of taking care of their aging parents. But as So-young slowly reconnects with past companions, she bares witness to their children’s neglect and apathy towards their debilitating parents, whose lonely existence is no less sorrowing and empty than her own. Once a family obligated tradition, this custom has now been forgotten as Korea’s strict social structure seeks change.

The consequence of Korea turning into a fast and highly competitive society has resulted in a limbo state where young people barely have enough resources to take care of themselves, let alone their parents. Leaving them to often to fend for themselves. In So-young’s case, even though she never had a chance to raise a family of her own, she finds comfort in her stand-in family of friends and neighbors that often shares the same emotions of loneliness as So-young. Though this family is represented as her saving net, So-young constantly wavers in indulging them with her past life secrets. Which often involve stories of her time as an American solider escort and the arduous decision to giver her baby son away for adoption.

As more tribulations of So-young’s life come to light, her snappy attitude begins to subdue as she cares for a young boy, Min-ho (Choi Hyun-jun), who is labeled as a “Kapino”: abandoned children of single mothers left behind in the Philippines by Korean men. Along with her transgender landlady Tina (An A-zu) and her amputee neighbor Do-hoon (Yoon Kye-sang), all four try to come to terms with being the outcasts of modern society, leaning on the surrogate family they have created to alleviate their abundant pain and loneliness. But as So-young goes about her daily life — having no desire to change her career — she is suddenly thrown into uneasiness when she contracts a sexually transmitted disease that puts a jarring hold to her routine.

The alarming truth is that Bacchus Ladies don’t just carry around drinks to lure in customers. They hoist a new epidemic that is a source of a major problem. Bacchus Ladies carry around a special Alprostadil suppository injection that helps elderly men perform better during sex. But those needles are hardly disposed of after just one use. And now a study finds that up to 40% of elderly Korean men test positive for an STD, which can lead to massive spreads and an incline in premature deaths. When So-young herself contracts an STD and can no longer offer herself for money, she enters an uncertain future, until she is visited by an old customer of her past that turns So-young towards a more ominous and dire lifestyle.

At a crossroad without a secure flow of income and struggling to keep her health in check, So-young is suddenly placed into a moral dilemma involving death and existence. The narrative moves forward, focusing on several of her past customers who forwardly ask her for assistance in dying. A rich business man now bedridden, a friend whose dementia is rapidly stealing away his memories and a recently widowed companion Jae-woo (Chon Moon-song), all seeking to die by their own terms. Many of the friends who come asking for aid are just a part of the 65% of elders that live below the poverty line in South Korea and those who are more likely to go into intense states of isolation and depression.

As So-young contemplates their daunting proposals for assisted euthanasia, she sees first hand the inescapable troubles that come naturally as one ages. And all the pain, loneliness and regret that stumbles closely behind. As she ultimately agrees to their proposals, she staggers in her own thinking about what death will be like for her as she nears its inescapable hooks. Will she be alone? Will it be a dignified death? Or is she meant for a miserable demise as a consequence of the path that she was forced upon? In many cases, So-young doesn’t face this path alone, most Korean elders have already imagined their deaths and more than anything wish it to come sooner, as in death no one is forced to clean up garbage off the streets for profit or stray the park looking for men to sell Bacchus drinks too.

The Bacchus Lady as both a cinematic film and as a social commentary on just one of Korea’s social issues, forces the viewer to dwell over the ideas of age and death. It brings to the surface the pain of those that are often pushed aside in society while still painting them as their own individuals. The difficulty that many elders of Korea face presently is the uncertainty for a better tomorrow. As the government pushes the epidemic aside to aid more urgent manners and as Korea’s low birthrate and youth unemployment, Korean elders will make a living taking up odd jobs. Most will collect cardboard on city streets or sell food in town markets. But many elderly Korean women, tilting towards desperation and hunger, are quick to settle for becoming Bacchus ladies. Calling places like Jongno Park their workplace.

Director E J-young has used his power as a writer and a producer to reflect on a major social issue that has been pushed aside beneath the mainstream flow of media. It is a film that captures divine and fresh characters that are hardly given any screen time in South Korean films but were not merely placed there for comedic relief. For the main protagonist So-young, her journey of being a Bacchus Lady transcends the line of film and is a direct reflection on the real life Bacchus Ladies of South Korea.

As the government — too leisurely — works on providing a better pension system for its aging citizens, the elderly population has no choice but to wait. It is estimated that by 2060, 90% of the population over the age of 64 will need some kind of pension. Meanwhile, Korean grandmothers will pack up their Bacchus drinks and make rounds throughout Jongno Park, searching for elderly men who are searching for them.

(CNN Money, Channel News Asia, BBC, CNN, The Korean Herald [1][2], The Korean Bizwire, Chosun Ilbo, NPR, Images via Media Asia Film Distribution.)