When it comes to talks of how sexuality is perceived in a particular place, it’s never a good thing to base one’s judgement solely on how the media depicts it. That’s because if there’s anything that the media has misrepresented the most in the course of its development over the years, it is that of human sexuality. One good example of this would be how the South Korean entertainment industry — K-pop in particular — portrays sexuality.

On the outside, one might applaud K-pop for finally creating ‘sex positive’ spaces that embrace alternative forms of femininity and masculinity. From the hyper-feminine ‘flower boys’ to the more sexually liberated and/or empowered female imagery, K-pop is supposedly more or less breaking barriers about what it means to be an Asian man or an Asian woman in the world of mainstream pop music and pop culture. However, as mentioned, these depictions are far from the reality of things.

In case some of you might have missed it, a fairly recent prostitution scandal broke out in the K-entertainment world with some rather unsettling revelations. The scandal was said to have involved some Korean female celebrities who have been characterized as either rising or waning stars that have struggled over the years with earning a decent income in the industry. The news reports and investigations have revealed that it was through the notion of “sponsorships” that these celebrities were being forced to engage in such activities.

Talking about the South Korean sex industry is in a way akin to discussing the infamous slave contracts of the K-pop world: everybody is aware of its highly questionable existence, yet it has been around for so long and has become sort of integral to the system that it’s mostly ignored. This is no surprise when young people (and even some working adults) in South Korea are very much unable to engage in sexual relations of various kinds because of how a majority of them still live with their families. In addition, the South Korean sex industry accounts for a significant percentage of the country’s total GDP, hence the reason why South Korea has been hailed as one of Asia’s prime destinations for sex tourism.

Talking about the South Korean sex industry is in a way akin to discussing the infamous slave contracts of the K-pop world: everybody is aware of its highly questionable existence, yet it has been around for so long and has become sort of integral to the system that it’s mostly ignored. This is no surprise when young people (and even some working adults) in South Korea are very much unable to engage in sexual relations of various kinds because of how a majority of them still live with their families. In addition, the South Korean sex industry accounts for a significant percentage of the country’s total GDP, hence the reason why South Korea has been hailed as one of Asia’s prime destinations for sex tourism.

However, apart from being a significant money-maker, the sex industry has bred an unnervingly remarkable culture of ignorance for the issues that plague it. This particular sense of ignorance is what’s driving the state to simply create laws that outrightly illegitimatizes the entire industry, and the fact that the South Korean society turns a blind eye to the nuances of the sex trade issue has led to a sincere lack of public discussion about what the sex trade means to those involved, namely the sex workers.

In short, it was a black or white situation for the citizenry: the sex industry is absolutely wrong; sex work is not honest work. Nothing more, nothing less. Tragically, this has then led to an unconscious sense of unaccountability among South Koreans in which active denial on the complex matters of sexual exploitation — and probably even sex in general for that matter — is a general trend.

As a Neo-Confucianist society, South Koreans have constantly upheld sexual purity especially among women and is a trait deemed integral to their individual worth. The historical roots of South Korea’s modern, Neo-Confucianist way of living has always depicted the chaste and virginal woman as desirable; hence her abstinence from sex or at the very least, her utmost intolerance for the vaguest sense of her sexuality was considered to be more valuable than her life. However, there were some women who departed from these strict rules of the Confucianist lifestyle and these were the kisaengs — free-spirited and sexually liberated women of the lower class. These women were in a way similar to the Japanese geisha: intelligent, educated, and highly-trained in the art of entertainment and pleasure.

As a Neo-Confucianist society, South Koreans have constantly upheld sexual purity especially among women and is a trait deemed integral to their individual worth. The historical roots of South Korea’s modern, Neo-Confucianist way of living has always depicted the chaste and virginal woman as desirable; hence her abstinence from sex or at the very least, her utmost intolerance for the vaguest sense of her sexuality was considered to be more valuable than her life. However, there were some women who departed from these strict rules of the Confucianist lifestyle and these were the kisaengs — free-spirited and sexually liberated women of the lower class. These women were in a way similar to the Japanese geisha: intelligent, educated, and highly-trained in the art of entertainment and pleasure.

The stark contrast between the ideally pure and submissive Confucianist woman and the seemingly liberated kisaeng eventually became South Korea’s own version of the Freudian madonna-whore complex, and just like that complex, the shaming of the female sexuality has become an intrinsic attitude among South Koreans, an attitude that stems from a culture that has a deep aversion from anything sex-related. By subscribing to these sexually conservative perceptions and opinions, the public is hindered from really bringing issues about sex (i.e. contraception, STDs, etc.) into public discourse.

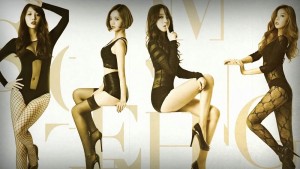

K-pop as an industry is rooted in this conservative way of thinking. The divide that exists between ‘sexy girl group concepts’ and ‘pure and innocent concepts’ is clear, and while such marketing ploys might seem harmless, the deeply rooted sentiment for this divide is slut-shaming. K-pop’s portrayal of the madonna-whore dichotomy in the industry reinforces the ‘general consensus’ that the pure and innocent girl is the more socially acceptable and morally upright one while the sexually liberated female is ‘tainted’ and seen as the ‘less respectable’ one of the two.

K-pop as an industry is rooted in this conservative way of thinking. The divide that exists between ‘sexy girl group concepts’ and ‘pure and innocent concepts’ is clear, and while such marketing ploys might seem harmless, the deeply rooted sentiment for this divide is slut-shaming. K-pop’s portrayal of the madonna-whore dichotomy in the industry reinforces the ‘general consensus’ that the pure and innocent girl is the more socially acceptable and morally upright one while the sexually liberated female is ‘tainted’ and seen as the ‘less respectable’ one of the two.

HyunA of Cube Entertainment’s 4Minute is a clear example of the ruthlessness of slut-shaming in K-pop. When HyunA broke out as a solo artist and was marketed with sexy concepts, K-pop fans were quick to criticize and judge her without even a hint of consideration on the fact that these marketing decisions might have not been entirely her own. The way her company conceptualized her solo idol persona and the way fans would shame HyunA by commenting on how her new sexy image took away from who she is as a person and as an idol dancer is once again a manifestation of South Korea’s narrow perception of female sexuality and once again, sex as a whole.

It is for this reason that slut-shaming makes a horrible contributor to the issue of sexual exploitation in South Korea. It is the judgement that because these sex workers ‘chose’ this life, they have been illustrated as undeserving of genuine help and sympathy. As Korean-American brothers and filmmakers Jason and Edward Lee so explored in their documentary Save My Seoul (which is about the rampant underground South Korean sex trade), something is ‘broken’ in South Korean culture that somehow makes it acceptable to condone the industry, and it is mostly because of how society sees and treats the girls involved in the the sex trade business.

As mentioned, although law enforcement against prostitution has been strict in South Korea, there’s no denying that with the continuous existence of the outright sponsorship practice in the entertainment industry (and the severe lack of regulation of South Korea’s sex industry), the root of the problem has not been directly and properly addressed. Rather, instead of campaigning for the genuine protection of those who are being exploited by such a system, it seems that these laws and policies were merely made in an attempt to guarantee South Korea’s consistent global competitiveness in being a model country that so-called condemns illegal sexual activities such as prostitution.

As mentioned, although law enforcement against prostitution has been strict in South Korea, there’s no denying that with the continuous existence of the outright sponsorship practice in the entertainment industry (and the severe lack of regulation of South Korea’s sex industry), the root of the problem has not been directly and properly addressed. Rather, instead of campaigning for the genuine protection of those who are being exploited by such a system, it seems that these laws and policies were merely made in an attempt to guarantee South Korea’s consistent global competitiveness in being a model country that so-called condemns illegal sexual activities such as prostitution.

However, due to how the culture continues to shy away from talks about the complexities of sex — especially that of the female sexuality — it very well appears that these policies were made in vain. In the end, unless South Korea as a society starts engaging in meaningful and substantial discourse about not just the sex industry, but sex — particularly that of female sexuality — as a whole, then the problem of sexual exploitation will continue to remain as one of their most heartbreaking secrets.

(NYU, Fromheretokorea, Netizenbuzz, Korea Times, International Business Times, Prague Post, Vice, Opendemocracy, Peninsularity, ChosonKorea.com, Scholarworks, The Grand Narrative, Moonrok, Thelearnedfangirl, Korea Times US. Images via New Daily, Dream Tea Entertainment, Cube Entertainment, rok-on.net, Koogle.tv, static.squarespace.com)