Note: This post is a summary and analysis of ethnographic work primarily done by Swee-Lin Ho, in “Fuel for South Korea’s ‘”Global Dreams Factory”‘: The Desires of Parents Whose Children Dream of Becoming K-pop Stars.”

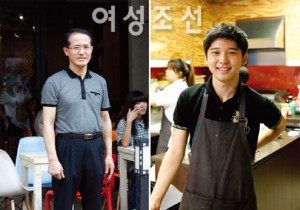

A pharmacist, a museum curator, and an idol trainee. Ten years ago, a Korean parent might have mentioned the last of these with less pride, if at all. Now the father of Kwon Jae-wook, a 17 year old K-pop hopeful, talks with equal excitement about all his children. He and his wife are participants in anthropologist Ho Swee-Lin’s ethnography of early-idol preparatory schools, basically hagwons for acquiring the skills necessary for later K-pop success. What’s becoming clear from this research is just how quickly a K-pop career, once a fringe aspiration, has reached mainstream acceptance. Furthermore, parents like Kwon’s are now willing to pay high costs to invest in their children’s dreams, even as the chances for success dwindle.

Much like parental eagerness for idol training, idol prep schools are a decidedly recent phenomenon. Traditionally, a large management company signs children as young as 12, many without performance experience. After signing 10-15 year contracts, these children attend rigorous training to one day vie for the small number of slots available in a debuting group. While employed, trainees receive monthly salaries, but most have no claim to royalties or musical licenses. Heavily influenced by the Japanese jimusho system, K-pop management companies take great risk to train fresh idols, without any guarantee of future dividends.

In contrast, idol prep schools are private institutions, separate from agencies and funded 100% by the parents of the children attending. The goal of these institutions is not to debut talent, but to impart upon idol hopefuls the skills necessary to one day sign as a trainee. While this decentralized, parent-influenced system is more similar to American idol training, it lacks the promise of big rewards upon attainment of success. If selected for an agency, the young artist will still be a salaried employee, and thus not necessarily entitled to earnings that commensurate with sales. The best long term reward that a parent can hope for is a filial idol, a grateful son or daughter who uses his earnings to repay his parents with expensive gifts.

Korean TV shows are quick to flaunt famous filial acts, particularly Super Junior’s Yesung’s purchase of an apartment and cafe for his family and 2AM’s Jo Kwon’s fulfillment of his promise to purchase a family home. As part of a contest to determine the most filial idol, hosts on Noreowa recited long lists of so-called filial acts to listeners at home. Parental honor even claims space in song lyrics. miss A’s recent hit “I don’t need a man” includes lines about members giving allowance to their parents. However, traits like these don’t just represent altruistic behavior, but carefully constructed aspects of an idol’s personality. Paying tribute to parents (and to agency and country) is one of many behavioral traits expected of successful idols, a character complex collectively known as inseong gyoyuk.

Korean TV shows are quick to flaunt famous filial acts, particularly Super Junior’s Yesung’s purchase of an apartment and cafe for his family and 2AM’s Jo Kwon’s fulfillment of his promise to purchase a family home. As part of a contest to determine the most filial idol, hosts on Noreowa recited long lists of so-called filial acts to listeners at home. Parental honor even claims space in song lyrics. miss A’s recent hit “I don’t need a man” includes lines about members giving allowance to their parents. However, traits like these don’t just represent altruistic behavior, but carefully constructed aspects of an idol’s personality. Paying tribute to parents (and to agency and country) is one of many behavioral traits expected of successful idols, a character complex collectively known as inseong gyoyuk.

This suite of personality traits is so important that idol prep schools teach it along with singing, dancing and body management. It’s components — politeness, respect, humility, gratitude, filial piety, kindness, compassion, selflessness and self-sacrifice — would not feel out of place in a Confucian treatise on family values. Demonstration of inseong gyoyuk primarily requires submission to the guidance of the head of the family — or agency, as this is a metaphor that many talent management companies have readily adopted. While it’s easy to see the benefits of having docile and obedient trainees, parents also seem happy to have these values instilled in their children. As the father of trainee Yoo-Seok Lim says “If success has not turned some popular idols into selfish or ungrateful people, I can hope that my son could also be filial.” The desires of agencies and families converge in the desire of a child who publically acts with inseong gyoyuk.

Of course, the short-term reward of an obedient child seems small in the wake of the huge investment required for students to attend these programs, especially given the small chance of a successful return. Of all the students in idol prep school, only a few will become trainees of the big entertainment conglomerates, and even fewer will manage to debut as an artist. Thus, the monetary investments made by parents –sometimes totaling more than 40% of their monthly household income– represents a huge gamble with few tangible dividends. Furthermore, since these prep schools are so new, families are investing money into this system without knowing if it will increase the chance of their child becoming an official trainee.

Yet, parents are willing to move to smaller houses, take on part time jobs, and debilitating debt, to fund their child’s progress. While families have always been willing to make financial sacrifices for academic pursuits, the trend in spending the annual US$12,000 charged by a top idol prep schools reflects changes in fundamental societal values. Based on Ho’s data, parental pride from a child fulfilling their idol dreams now resembles pride once generated only from academic success.

Yet, parents are willing to move to smaller houses, take on part time jobs, and debilitating debt, to fund their child’s progress. While families have always been willing to make financial sacrifices for academic pursuits, the trend in spending the annual US$12,000 charged by a top idol prep schools reflects changes in fundamental societal values. Based on Ho’s data, parental pride from a child fulfilling their idol dreams now resembles pride once generated only from academic success.

This is particularly evident in mothers of K-pop trainees, many of whom spent years receiving blame for their child’s academic failures, and who now feel relieved at the prospect of success though alternative methods. Hye-jin Park’s mother attests that in two years, her daughter has attended Z Academy, an idol prep school, she has grown from a petulant child who struggled with schoolwork into a budding star with vocals “as powerful as Whitney Houston’s” and the looks and confidence to “marry someone rich and famous.” Enthused by her daughter’s success, Hye-jin’s mother has taken to managing her career more closely, noting her plastic surgery options and monitoring her daily diet. Similarly Jae-wook Kwon’s mother, who for years was blamed for his lack of ambition, has gained acceptance within the family for her son’s success at Z Academy. She admits to Swee-Lin “I don’t know what they did to him at Z Academy, but I am so relieved I can now hold my head high when I meet my friends and relatives.” The stories of these mothers suggest that, rather than a localized process, the acceptance of K-pop as a worthwhile career is a national phenomenon.

This re-branding of K-pop is a testament to an aggressive government campaign, aimed at legitimizing K-pop careers nationally to increase the chance of success internationally. Like Korean dramas before it, K-pop represents a form of soft cultural power, or the ability for worldwide acceptance generated by non-aggressive means to influence international politics. K-pop has inundated the international market with marked — if not perfect — success, and this has caught the attention of the country’s leaders. After the accomplishments of K-pop tours worldwide, particularly in Paris in May 2011, the government invested 794 million dollars in 2011 towards various idol endeavors. Subsequently, however, these investments have come under criticism for being unfocused, contradictory, and excessive.

Perhaps even more successful has been alignment idol culture with long-held cultural values represented by inseong gyoyuk. This has involved equating K-pop stars with national heroes, a logical step given the shared goals of government and talent agencies. Notably, rather than the government intentionally driving the shift towards broad K-pop acceptance, it appears to have emerged organically from the wave of enthusiasm generated by its global success and subsequent media coverage. Parents feel that the government’s willingness to spend money lends acceptability to the pursuit of an idol career, and the government sees the growing pool of new idols as justification for spending more money. Everyone is awash in nationalistic pride, but the instability of this tautological system is readily apparent.

Perhaps even more successful has been alignment idol culture with long-held cultural values represented by inseong gyoyuk. This has involved equating K-pop stars with national heroes, a logical step given the shared goals of government and talent agencies. Notably, rather than the government intentionally driving the shift towards broad K-pop acceptance, it appears to have emerged organically from the wave of enthusiasm generated by its global success and subsequent media coverage. Parents feel that the government’s willingness to spend money lends acceptability to the pursuit of an idol career, and the government sees the growing pool of new idols as justification for spending more money. Everyone is awash in nationalistic pride, but the instability of this tautological system is readily apparent.

Reading Swee-Lin’s work, a similar sense of transience emerges. Parents, idol agencies and the government all hope to instill inseong gyoyuk in idol trainees, but the motives driving the shared goal are so radically divergent that they necessarily produce conflict. Parents want to raise obedient, successful children, agencies hope to instill docility in their trainees, and the Korean government wants to mobilize K-pop as a form of soft power. Like a family, all parties make sacrifices for the trainees. However, only for individual mothers and fathers are the monetary investments so huge that a child’s success or failure has immediate ramifications for the family’s quality of life.

There are consequence for agencies too. The decentralization of idol training away from the three big agencies necessarily detracts from their power, granting them instead to the mothers and fathers footing the bills. Family is a powerful metaphor, both for these agencies and for the government’s attempts to link K-pop with traditional Korean values, but giving decision making power to individual idols’ families in fact detracts from their goal. Rather, these institutions want parents to be passive receivers of gifts and gratitude.

Idol prep schools are perhaps best thought of as an unintended side effect of swelling national sentiment. In years to come, the fundamental tension may radically alter the fate of these schools. If agencies see idol prep schools consistently producing the next generation of K-pop stars, there might be more direct early involvement on the part of the agency. Alternatively, if there is no relationship between early investment and future success, parents might decide that their investment is better spent elsewhere.

Idol prep schools are perhaps best thought of as an unintended side effect of swelling national sentiment. In years to come, the fundamental tension may radically alter the fate of these schools. If agencies see idol prep schools consistently producing the next generation of K-pop stars, there might be more direct early involvement on the part of the agency. Alternatively, if there is no relationship between early investment and future success, parents might decide that their investment is better spent elsewhere.

For now, parents soldier on, attending student performances and assuring themselves that their children have the vocal, dance and personality traits required to debut as a global K-pop star. With the new esteemed place held by K-pop artists in Korean society, many feel that the boost in social status justifies the immense investment in a hopeful child’s future in entertainment. If students like Jae-wook and Hye-jin are successful, the social, but not financial, reward will be even larger. If they aren’t, at least they have become better idols — or at least better citizens.

(Ho (2012), Jung (2012), Lie (2012), Woman Chosun, KoreaDaily, DM SKOOL)