Hello everyone, and welcome back to another SB Exchange! This week we look to the east–more specifically, Japan.

Hello everyone, and welcome back to another SB Exchange! This week we look to the east–more specifically, Japan.

Despite a complicated history existing between the two countries, which continues to create conflict, Hallyu has been able to spread relatively unhindered in the last decade, notably starting with the runaway success of Winter Sonata. K-pop began its Japan campaign with the debut of a teenage BoA in 2001. The positive reception she received paved the way for more K-pop acts to try their luck, from a trickle of groups to the veritable flood of every nugu and their mum that we see today, in 2012. With this move has also come a change in how fans also consume K-pop: we are watching PVs, trying to stream Music Station and even analysing sales figures.

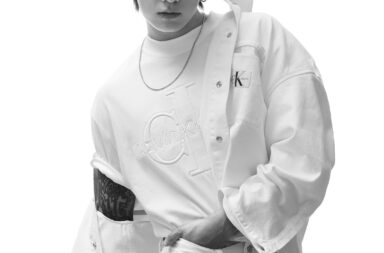

My first brush with K-pop’s Japanese efforts came in the form of SNSD‘s “Genie” PV. I thought I was going to watch the same MV I had watched the previous day, with the lit-up heart backdrop and the rather creepy first-person viewpoint–instead I saw an attic, giant confectionary, dog tags and gingham. It was wondrous, yet also a bit disconcerting, even for someone used to seeing artists moving between languages frequently (in India). Many K-pop fans came to the genre from J-pop and/or Anime, but there are also fans for whom Japan and Japanese music is a new experience: and so, I’ve called upon Nicholas Jasper and Amy to lend their expertise and give an overview of K-pop in Japan.

1. How have K-pop groups adapted to the Japanese market? Are they presented any differently in Japan than they are in Korea?

Nichloas: Generally most K-pop groups tend to export their most well known songs, because the first thing in Japan was to forge their identity, no matter how trite the export is. However, with time, most of these acts did forge their own identity with unique songs that proved that it was not just a money grab.

I feel that in Japan, most groups tend to go with songs with more traditional composition styles and far better use of vocal layering, compared to Korea where they work more on the hook.

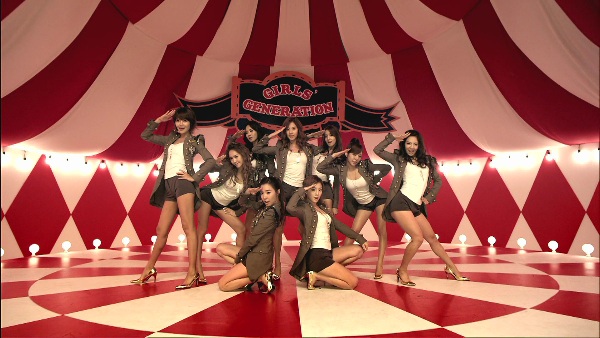

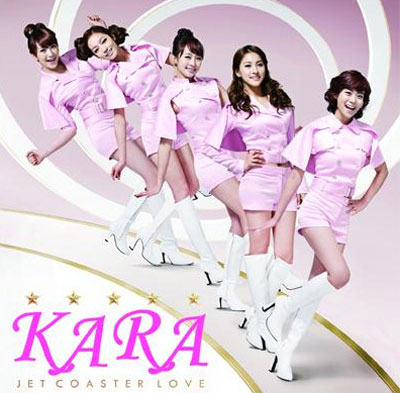

Jasper: A group wants their debut to be representative of their past, yet telling of their direction in the future, allowing them to eventually adapt.And what better way to show these things than remakes. While remakes are definitely get on plenty international fans’ annoyance, they are a pretty great way to gain security. And security is essential for a group planning to crossover to a different market. I’d consider Shoujo Jidai’s (SNSD) “Genie” and Kara‘s “Mister” to be very successful debuts, basically showing what the groups embodied back at home and also setting the tone for all of their future releases.

Jasper: A group wants their debut to be representative of their past, yet telling of their direction in the future, allowing them to eventually adapt.And what better way to show these things than remakes. While remakes are definitely get on plenty international fans’ annoyance, they are a pretty great way to gain security. And security is essential for a group planning to crossover to a different market. I’d consider Shoujo Jidai’s (SNSD) “Genie” and Kara‘s “Mister” to be very successful debuts, basically showing what the groups embodied back at home and also setting the tone for all of their future releases.

As to how these idols are presented differently in Japan rather than Korea, I’d honestly like to say they’re painted more as artists rather than idols. Back in Korea, the term “idol” is so rigidly defined, and these groups were most likely some of the more triumphant examples, keeping them from breaking this mold. Japan’s more diverse pool of music tastes allows these idols to explore a bit more in foreign soil, temporarily shedding their idol label to a degree. Also, while Japan has its own idol market, there are vast differences between the two genres. Don’t get me wrong, the two parties are still major competitors. They share similar demographics and traits, but in Japan, there are groups with more members in them, groups more willing to be cute or sexy then their counterparts, groups more willing to push the envelope a bit more. So it would be slightly redundant for K-pop groups to try to outdo their counterparts, since it’s a whole new ballgame with new competitors and new rules.

Consequently, these groups are rather painted as exotic and desirable, and as such take relatively more mature and less concept-driven routes. They rely less on hooks and gimmicks, and more on actual musical production, actually allowing these “artists” to grow.

Amy: I think groups have adapted less their image than they have with their music. I think it’s safe to say that all the groups that do extremely heavy promotion in Japan — not the throwaway here and there — have better Japanese discographies than they do Korean ones. Their music is tailored to the Japanese market before their images are and I think there’s a tendency to have to up the ante when artists go over to Japan, mostly after groups have already remade their Korean singles.

When groups start to pump out original Japanese material, it’s often stronger than their Korean singles and albums. This might be because the Japanese market is hard to win over, especially given the two countries’ unease with each other and there’s a certain need to impress and to assert legitimacy, but Korean artists’ original Japanese material often feels much fresher, less stagnant.

2. Leaving aside BoA, Tohoshinki, Kara and SNSD, who do you think has made a successful splash in their Japan venture, and who hasn’t?

Nicholas: Acts who have been recognised overseas tend to be those who have made an attempt to assimilate and work from the ground up. A good example would have been DGNA (The Boss), who before the Open World Entertainment incident, were known for their speaking of Japanese without translators, as well as getting the basics right (quality vocals and live performances).

On the flipside, far more groups have bombed or failed to make an impact. Chalk it down to having overly generic tunes (After School), weak grasp of the Japanese language (2NE1) or even just not really trying (Secret).

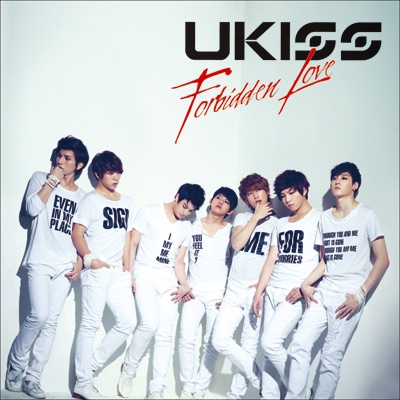

Jasper: Surprisingly (or maybe not surprisingly), Korea’s boy groups have managed to make bigger splashes rather than their female counterparts (barring Shoujo Jidai and Kara of course). Big Bang and 2PM are doing quite decently in Japan from what I remember, and U-Kiss and Supernova are arguably more popular in Japan rather than in Korea. IU‘s also been doing quite well last time I remembered.

Jasper: Surprisingly (or maybe not surprisingly), Korea’s boy groups have managed to make bigger splashes rather than their female counterparts (barring Shoujo Jidai and Kara of course). Big Bang and 2PM are doing quite decently in Japan from what I remember, and U-Kiss and Supernova are arguably more popular in Japan rather than in Korea. IU‘s also been doing quite well last time I remembered.

But I have to agree with Nicholas in that most other groups are failing quite pitifully. And it’s sad, since I thought most of these groups actually had some potential in the market. If only they didn’t make it so obvious they were only in it for the money…

Amy: I think groups like U-Kiss and T-ara are starting to make somewhat of a splash. It helps that the groups are continuously putting out singles, even if they’re not as frequent as SM’s roster of Japan-active groups. Surprisingly, groups like Big Bang and 2NE1 are doing less explosively than a lot of people anticipated. I think people assumed that YG‘s brand of music — which definitely has a stronger Western appeal than other K-pop’s music — would automatically translate to extreme popularity in Japan, but it really hasn’t.

3. The general consensus among K-pop fans (at least international ones) is that a group’s Japanese material is of a higher quality than their Korean material. Why do you think that is?

Nicholas: I think it is the whole point of being overseas. While promoting in a foreign country there is a lack of a local fanbase, unless there are fans who are more than willing to export albums to help push sales. So in that case, they really do have to appeal to locals. Another factor would also be wanting to achieve musical legitimacy overseas, so by putting in more effort in the foreign works, they are seen as succeeding not because of the novelty factor but because through quality music, they have made it.

Then again, it could just be the fact that they worked with the right producers who know how to find the right type of songs that worked for them.

Jasper: I really think this consensus only applies to the groups that are actively trying in the market. The original songs (if they have any, T-ara) of groups just breezing through their foreign promotions are quite forgettable, and it’s only really those that actively try (so Kara, THSK, U-Kiss) that see this considerable increase of quality.

Jasper: I really think this consensus only applies to the groups that are actively trying in the market. The original songs (if they have any, T-ara) of groups just breezing through their foreign promotions are quite forgettable, and it’s only really those that actively try (so Kara, THSK, U-Kiss) that see this considerable increase of quality.

But why are these releases considered to be of better quality? Well, I’d kind of attribute that to the idol vs. artist mentality I mentioned earlier. Since these idols are escaping their restricting idol label, they’re able to grow a bit more in this new market. Furthermore, the diversity in the Japanese music industry might influence experimentation compared to the highly saturated nature of the K-pop market.

More than that however, is that in this new foreign market, top idols have to compete for their name again, establish their brand practically from ground-up all over again. These groups, most likely among the best and most revered back home, can no longer just rely solely on their fame to achieve success. They can no longer release lazy, hook reliant releases that rack in sales simply because the group is top-tier. Now, they need to actually rely on their music once again to establish their name, increasing the quality of the songs and performances. This drive promotes growth and quality in the group, growth not necessary back home in Korea where these groups can just breeze through everything.

Amy: I touched on this for the first question, but I do think that a lot of groups get complacent with releasing for their Korean fanbases. Once you reach a certain level of popularity, there’s no need to try, which is not even an insult at this point, it’s truth. Groups like Super Junior are the best example of this: the last three years of releases from Super Junior have been complete and utter trash and they know that they don’t need to exhaust resources to come up with something great when they can clearly coast on garbage.

But the Japanese market is a different beast. It’s something that groups need to strive for, much like the American market. You have to come up with something that does well in a market that has very wide-ranging tastes and has a lot of money to spend on quality goods, so K-pop has to reinvent itself a little whenever groups cross over.

4. Are there lessons from Japan that K-pop can bring back home?

Nicholas: As mentioned earlier, the quality of music production. From how they layer the sounds to make a tune, to how vocals are mixed such that even mediocre singers can sound competent, Japanese producers offer many lessons worth learning. Their skills far surpass many Korean producers, who largely tend to depend on hooks or lack variations in sounds used.

Nicholas: As mentioned earlier, the quality of music production. From how they layer the sounds to make a tune, to how vocals are mixed such that even mediocre singers can sound competent, Japanese producers offer many lessons worth learning. Their skills far surpass many Korean producers, who largely tend to depend on hooks or lack variations in sounds used.

Another thing interesting is how J-Pop comes across as far more diverse, partly because they seem to acknowledge that popular music can come in many forms beyond the idol group. They know the other genres, and the music comes across as far richer for it.

Finally, stage performances and charisma levels. Japanese acts always make for fun watching, if because they do lay off the lip sync (hence what is heard is usually the artiste’s performance level), as well as what they put into a performance. You get the feeling they are really there because they love the stage, rather than due to the need to fulfill a broadcast schedule.

Jasper: Diversity. Japan’s music market is full of diversity, the market able to sustain all the different genres quite laudably. No one genre dominates the Japanese popular music scene, with genres such as J-rock and J-indie having their own commendable followings. In comparison, Korea’s popular music scene is insanely idol based, and the idols themselves are lacking in diversity as well. Granted, Japan does have a much bigger market compared to Korea, and thus, they’d be able to better manage all these genres and keep them popular. But a little more diversity in Korea’s music scene would definitely do it good.

Amy: Other than learning to not be complacent, it’s that live performances really, really matter. DBSK started promoting in Japan hardcore at a time when live performances in Korea were non-existent and they had to deal with the consequences of not having done a lot of lives until then. And it was around that period that live performances became a mainstay on Korean music shows. There are a ton of groups that debut now that don’t even have any intention of going overseas but can’t even handle something as simple and as much a prerequisite as performing properly live.

5. And for Japan and its music industry, what do you think it can learn from K-pop and the Hallyu wave?

Nicholas: For all the things that J-Pop does well, one thing they really cry out for is some sharp marketing. Surely being the original creator (and semi-successful exporter) of popular culture has got to count for something, as well as the years of added experience. My feeling is that J-pop right now is quite like the Galapagos of popular culture, evolved and self sustaining, with a little bit of inaccessible cool air about it. How about taking that, and spinning it into something that is an acquired taste, yet enjoyable once you get the hang of it? Judging from online buzz, there are many acts that have had a devoted following purely on word-of-mouth, so why not play on that slightly “underground” vibe.

Nicholas: For all the things that J-Pop does well, one thing they really cry out for is some sharp marketing. Surely being the original creator (and semi-successful exporter) of popular culture has got to count for something, as well as the years of added experience. My feeling is that J-pop right now is quite like the Galapagos of popular culture, evolved and self sustaining, with a little bit of inaccessible cool air about it. How about taking that, and spinning it into something that is an acquired taste, yet enjoyable once you get the hang of it? Judging from online buzz, there are many acts that have had a devoted following purely on word-of-mouth, so why not play on that slightly “underground” vibe.

Another thing that makes J-pop that little bit inaccessible is how so much online content gets walled off due to copyright or translation issues. Granted, there is the issue of getting paid and accurate translations (something which K-pop still works on half the time), but hey, open the gates and watch the fans come.

Jasper: As for what Japan can get out of Korea, I’d definitely agree with Nicholas and say marketing. While there’s no real need to since Japan’s large music industry can surely sustain itself, reaching out to foreign fans could potentially really help the genre. The effective ways K-pop management markets the genre allows their fans to feel more involved despite being so far away, and Japan could benefit from this as well.

Amy: Japan is completely miserable at spreading their music products outside of Japan. Like Jasper and Nicholas have mentioned, Japan has no need to do this, given that its own market can sustain its music industry extremely comfortably without outside help, but at a certain point, it starts to read like arrogance. This is a global age. It’s close-minded for Japanese music companies to shut out YouTube as aggressively as they have. It’s just unthinkable and extremely irritating for fans trying to get a better sense of Japan’s pop cultural products to be unable to find leads anywhere. It doesn’t help that merchandise coming out of Japan is ridiculously overpriced either, so it’s like Japan is actively trying to discourage anyone from gaining access to their pop culture, which is short-sighted.

——————————

As accurate a term “Galapagos of popular culture” is, I think Japan is slowly starting to put itself out there on the international music scene. Warner Music Japan, for instance, now shows the full PVs on their official YouTube channel, meaning that I can now watch Kyary Pamyu Pamyu dance around in pink vomit as much as I want. Another more prominent example would be that of electropop trio Perfume. A household name in Japan, they did not even know the extent of their fame until they were invited to the U.S. premiere of Cars 2 (their song “Polyrythym was featured on the soundtrack) and met their American fans for the first time. Seeing this prompted their agency Amuse Entertainment (whose Korean arm manages Cross Gene) to switch labels from Tokuma Japan to Universal J, and the trio is now in the midst of a world tour.

As accurate a term “Galapagos of popular culture” is, I think Japan is slowly starting to put itself out there on the international music scene. Warner Music Japan, for instance, now shows the full PVs on their official YouTube channel, meaning that I can now watch Kyary Pamyu Pamyu dance around in pink vomit as much as I want. Another more prominent example would be that of electropop trio Perfume. A household name in Japan, they did not even know the extent of their fame until they were invited to the U.S. premiere of Cars 2 (their song “Polyrythym was featured on the soundtrack) and met their American fans for the first time. Seeing this prompted their agency Amuse Entertainment (whose Korean arm manages Cross Gene) to switch labels from Tokuma Japan to Universal J, and the trio is now in the midst of a world tour.

The points brought up by Amy, Nicholas and Jasper in response to my last question have also been noted by Japanese artists, it seems. Perfume’s A-chan said in an interview with The Japan Times:

“The Korean language sounds really cool, and K-pop artists do that thing where they repeat one word over and over, which is really appealing…When a Korean artist comes to Japan they often speak (to fans and media) in Japanese, which is wonderful…”

While these Kyary and Perfume are not representative of the whole of the J-pop industry, I hope that they are like pioneers of sorts, and that other artists will follow suit in being more open to international interest like K-pop has. So, there is some information exchange happening, with Japan learning from Korea and I would love to see this go the other way as well. Getting rid of hand-syncing would really help bands better perform their songs on music shows, for instance. Idols have become a cultural export and tourist attraction for Korea, but diversifying their music industry will be important for the growth and continuity of the Korean music industry.

What do you think about the two industries? What are your favourite Japanese releases by K-pop acts? Share your thoughts with us below?

(SM Entertainment, DSP Media, Cor Contents Media, EMI Japan, Warner Music Japan, Universal Music Group, The Japan Times, Ayominho)