There are two constant music loves in my life: K-pop and hip-hop. Unfortunately I oscillate back and forth between them like a terribly finicky girlfriend when either of them starts to get on my nerves. I’m sure many of you have gone through phases when you have to take a break from something for a while so you can get back to it later with better appreciation. I’ve grown up with hip-hop and watched its evolution from political and social commentary, to gangsta rap, on to conscious lyrics, and then to party music. Hip-hop has gone through changes that its pioneers never dreamed possible. It’s become global. Which is why, when my ears first perked up to mainstream K-pop, it didn’t surprise me that most of their songs added in rap lyrics.

There are two constant music loves in my life: K-pop and hip-hop. Unfortunately I oscillate back and forth between them like a terribly finicky girlfriend when either of them starts to get on my nerves. I’m sure many of you have gone through phases when you have to take a break from something for a while so you can get back to it later with better appreciation. I’ve grown up with hip-hop and watched its evolution from political and social commentary, to gangsta rap, on to conscious lyrics, and then to party music. Hip-hop has gone through changes that its pioneers never dreamed possible. It’s become global. Which is why, when my ears first perked up to mainstream K-pop, it didn’t surprise me that most of their songs added in rap lyrics.

Ok, I’m lying. It did surprise me.

Not at first though. In fact, I didn’t consider the “rap sections” in K-Pop songs to be actual raps. Just talky lyrics sprinkled with random, strange, and repetitive English lyrics (seriously, I don’t know how many times I’ve heard the phrases “So high, touch the sky” and “Your love, sent from above”). It wasn’t until I started noticing a trend of K-pop music mistaking rap, hip-hop culture, and black culture for synonyms of each other that I started to think a bit more critically about the use of raps and the “rap image” in K-pop music.

For example, B.A.P. recently released their track “No Mercy,” which is slowly solidifying itself as one of the coolest summer comebacks. I like it too. Even with Bang Yong-guk sporting a Tupac-esque bandana and some cornrows. The first thought I had upon seeing his styling was: “People still wear cornrows? What is this, 1998?” My following thought was: “Wait, is he trying to be black? Is it because he’s rapping?” Before I make the assertion that cornrows are an inherently black thing and everyone else sporting them are posers, I want to take a step back and stop talking about cornrows for a second to explore what K-pop thinks hip-hop actually is. Since hip-hop (or is it just rap?) has and is being embedded into K-pop music, I’d like to look at the kinds of images K-pop uses to express that something is hip-hop and how hip-hop culture–and even black culture–is perceived by the K-pop industry.

For example, B.A.P. recently released their track “No Mercy,” which is slowly solidifying itself as one of the coolest summer comebacks. I like it too. Even with Bang Yong-guk sporting a Tupac-esque bandana and some cornrows. The first thought I had upon seeing his styling was: “People still wear cornrows? What is this, 1998?” My following thought was: “Wait, is he trying to be black? Is it because he’s rapping?” Before I make the assertion that cornrows are an inherently black thing and everyone else sporting them are posers, I want to take a step back and stop talking about cornrows for a second to explore what K-pop thinks hip-hop actually is. Since hip-hop (or is it just rap?) has and is being embedded into K-pop music, I’d like to look at the kinds of images K-pop uses to express that something is hip-hop and how hip-hop culture–and even black culture–is perceived by the K-pop industry.

First of all, where does K-pop learn about hip-hop and black culture? South Korea doesn’t have a particularly large African American population. Nor is hip-hop indigenous to South Korea. So where do some of the images and perceptions come from? Well, I’d venture a guess that it’s the same place a lot of people learn about hip-hop: television, music videos, movies, and radio. Images of rappers in the club popping bottles of Hennesy, old 90s flicks of gangs in Los Angeles with rap music as their backtrack and explicit radio content boasting money and bravado.

They’re the kind of images that lead a group like Big Bang to dress up like West Coast gang bangers and perform in front of a Korean audience:

After writing about this issue in the past, many of our readers adamantly claimed that Big Bang’s styling had nothing to do with the gangster image. The all-red clothing that they were wearing had nothing to do with the infamous bloods gang, recognized for their red attire. How could Big Bang possibly know about American gangs when they live allll the way in Korea?

Pfft. Yeah right.

You’d be surprised how familiar G-Dragon is with American culture, specifically hip-hop. That boy can comfortably quote Tupac’s All Eyez on Me, is not afraid to tell an English-speaking crowd to get their “motherf***in hands up!” and dances with T.O.P. like a madman to 50 Cent’s Candy Shop. I’m quite sure G-Dragon and the rest of Big Bang know a thing or two about hip-hop and black culture. Or, as I’ve said before, Big Bang didn’t learn about hip-hop from watching Taylor Swift videos.

You’d be surprised how familiar G-Dragon is with American culture, specifically hip-hop. That boy can comfortably quote Tupac’s All Eyez on Me, is not afraid to tell an English-speaking crowd to get their “motherf***in hands up!” and dances with T.O.P. like a madman to 50 Cent’s Candy Shop. I’m quite sure G-Dragon and the rest of Big Bang know a thing or two about hip-hop and black culture. Or, as I’ve said before, Big Bang didn’t learn about hip-hop from watching Taylor Swift videos.

However, just because Big Bang really likes and is influenced by hip-hop doesn’t mean that they knew exactly what those red outfits symbolized. Otherwise, they probably wouldn’t have been performing with heaps of mascara on and smiling faces while taking on the role of violent gangsters who, in real life, sell drugs, kill people, and ruin communities. The problem seems to be that K-pop groups are quite familiar with the surface of rap and hip-hop culture, but don’t understand the implications of certain images. Rather, they consume the culture without comprehending it, then regurgitate the incomplete leftovers. What this essentially does is produce a caricature of hip-hop that’s reflected by cornrows, bandanas, and lyrics delivered in aggressive tones. But where is the context? As one blogger from the New Organizing Project explained when expressing her feelings about K-pop’s use of hip-hop elements,

There [doesn’t] seem to be any acknowledgment of the originators and pioneers of hip-hop nor an understanding of the ways in which hip-hop grew out of a state of oppression and its use in engaging multiple social movements.

The context of hip-hop is lost in mainstream K-pop in favor of the “cool-factor.” Hip-hop signifies “cool” and more importantly, “black” or “black-ness” signifies cool. Without getting too in-depth about the historical relationship between blackness and cool, it’s fueled by African Americans’ pioneering of jazz, rock and roll, rhythm and blues, and of course, hip-hop–all of which acted as rebellious antitheses to standard American music of the era.

As an example of how many K-pop artists associate black with cool, I’d like to call out C.N. Blue‘s Yonghwa for how he transformed into a thug-life incarnate during an interview with a young African American girl.

To this day, I’m still wondering why Yonghwa turned into Ice Cube all of a sudden. Was it because he was being interviewed by a black girl? His more forceful manner of speaking mixed in with a couple of “yo-s” here and there were probably his way of showing that he’s cool and hip. He’s down with the lingo if you will. Newsflash, Yonghwa, you don’t need to act like Snoop Dogg to show that you’re cool. Flashing your incredibly toned arms will suffice.

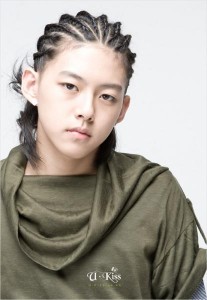

K-pop’s stunted conception of hip-hop is evidenced by all of the above. But what about one of the hugest elements of hip-hop? Rap. One of the biggest misconceptions the mainstream idol industry has about rap is that it’s easy. Just throw in a laughably ill thought-out rap right before the bridge of a song and that should do it. In fact, the K-pop idol rapper is often times the group member who has limited vocal talent. The rap is regarded as the afterthought. Take, for instance, this U-Kiss interview, where the members were asked what their roles were in the group:

Dongho: Uhh, I’m the cute one.

Soohyun: …And?

Dongho: Yes, that’s all.

Soohyun: And rap?

Dongho: Oh yeah. And rap.

Other than the fact I find this conversation utterly hilarious, I still find it quite telling that the K-pop industry’s understanding of rap is limited, and even pejorative. It’s almost as if the rapper of the group is considered the most useless one, right below the visual. The notion that rap is actually supposed to mean something and that raps actually have to be finessed and fleshed out, is non-existent in mainstream K-pop.

Other than the fact I find this conversation utterly hilarious, I still find it quite telling that the K-pop industry’s understanding of rap is limited, and even pejorative. It’s almost as if the rapper of the group is considered the most useless one, right below the visual. The notion that rap is actually supposed to mean something and that raps actually have to be finessed and fleshed out, is non-existent in mainstream K-pop.

But quite frankly, well thought-out lyrics are almost non-existent in mainstream American hip-hop, too. I can’t express how many times I’ve had to turn off my radio because of embarrassingly basic rhyme patterns and really, really stupid wordplay. Since Seoulbeats is not a hip-hop blog, I won’t go into the deep and dark pitfalls of the genre (and how it too has used stereotypical images of Asian culture). But it’s important that rappers–specifically American rappers–understand that hip-hop has long been global. The images that are portrayed in hip-hop videos (and even film/television portraying black culture) are no longer situated just in small communities but also across the globe from France, to India, to South Korea. So while the majority of hip-hop music is littered with aggression, misogyny, and all-around disfunction, everyone everywhere is now watching.

I say all that, however, to emphasize that I love the blending of cultures and the merging of genres. I squeal every time I hear a K-pop artist use a line from an American rap song. And I also blew a gasket when Nicki Minaj used Hangul to caption her entire “Check it Out” video. Epik High and Tasha are two of the most talented acts in hip-hop, period, and have proven that they understand it better than most. And despite my criticisms of Bang Yong-guk, G-Dragon, and T.O.P. (all written out of love, folks), I sincerely believe that they can all legitimately rap. I’ve managed to, thus far, avoid using the words “cultural appropriation” only because it sounds so sinister. So I’ll end by simply saying that hip-hop shouldn’t be blatantly used as a marketing tool to make groups seem cool and edgy, nor should it act as an excuse for K-pop artists to caricature both black culture and hip-hop culture.

I say all that, however, to emphasize that I love the blending of cultures and the merging of genres. I squeal every time I hear a K-pop artist use a line from an American rap song. And I also blew a gasket when Nicki Minaj used Hangul to caption her entire “Check it Out” video. Epik High and Tasha are two of the most talented acts in hip-hop, period, and have proven that they understand it better than most. And despite my criticisms of Bang Yong-guk, G-Dragon, and T.O.P. (all written out of love, folks), I sincerely believe that they can all legitimately rap. I’ve managed to, thus far, avoid using the words “cultural appropriation” only because it sounds so sinister. So I’ll end by simply saying that hip-hop shouldn’t be blatantly used as a marketing tool to make groups seem cool and edgy, nor should it act as an excuse for K-pop artists to caricature both black culture and hip-hop culture.

(Girls Like Giants, NAKASEC, voice6888, kfm9638, YGE)