While Japan and Korea have never gotten along very well, the latter’s annexation by the former in 1910 made relations between them down-right nasty. At the end of the occupation in 1945, South Korea actually banned all Japanese cultural imports from entering into the country, and remained embittered when Japan refused to fully apologize for what they’d done. Japan, in turn, found Koreans (like every other non-Japanese group) to be a lowly bunch, and wished they’d just shove off.

While Japan and Korea have never gotten along very well, the latter’s annexation by the former in 1910 made relations between them down-right nasty. At the end of the occupation in 1945, South Korea actually banned all Japanese cultural imports from entering into the country, and remained embittered when Japan refused to fully apologize for what they’d done. Japan, in turn, found Koreans (like every other non-Japanese group) to be a lowly bunch, and wished they’d just shove off.

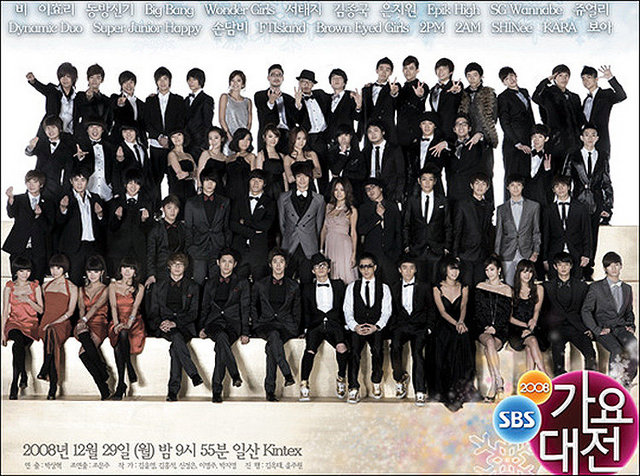

So when the ban was finally lifted between 1998 and 2004, the Korean media was shocked to learn about Japan’s rising interest in their drama programs. And thanks to the internet, curious Winter Sonata fans were discovering Korea’s new, increasingly popular export, K-pop. Korean culture was turning heads.

The first Korean artist to actually break into Japan and top the Oricon charts was BoA. Her Korean album debuted in 2000. The following year she began introducing her music to Japan, and by 2002 she had released her first full Japanese album. Putting her country on the backburner for a while, she devoted all of her energy to perfecting her Japanese and making her place in the Japanese music market. Over the years, she has had three albums selling more than one million copies in Japan (the only non-Japanese Asian to do so), and is one of two artists to have six consecutive number-one albums on the Oricon charts since her debut.

BoA is now considered to be both a Korean and a Japanese artist. The latter is attributed to not just her proficiency in the language, but to her having lived in the country for years learning about the culture so she might create music geared specifically toward her Japanese listeners. While some of her fellow Koreans feel she abandoned them and “sold out,” her Japanese fans recognize and appreciate her devotion. Boy group DBSK became similarly popular for the same reasons—by making a real effort to identify and communicate with the Japanese people.

Since BoA, multitudes of K-pop acts have flocked to Japan to make their own debuts.

The reason is simple: money. Japan has the second largest music industry in the world, and is a hop, skip, and a jump away from the homeland. Korea began pushing their cultural exports back in ’97 for the sole purpose of increasing national revenue, so incorporating Japan into the mix was perfectly logical. The K-pop acts tend get a decent reception (some more than others), but many Japanese stress that their popularity in here has been wildly exaggerated by the Korean media. Makes sense: more hype means more interest, and subsequently more profit. Forums reveal many K-pop/J-pop fans feel that presently, there are way too many K-pop acts debuting in Japan. It’s as if Korea is merely using Japan as a “side gig” to earn extra cash. These groups are usually sent over speaking exceptionally poor Japanese (if any at all) and know nothing of the culture. Many see this as a complete lack of respect for the Japanese people and can find no reason for these K-pop bands to even to be here. In their eyes, if Korean acts aren’t going to make an effort like BoA or DBSK, they should just go home. For critics, the only saving grace is the belief that this K-pop craze is no more than a passing fad that will disappear just as quickly as it came.

Still, despite the anti-K-pop sentiments, many of these diligently trained acts do have a Japanese following. On July 14th, Mnet Japan aired a show called “Boom the K-pop,” which focused on girl group SNSD’s popularity and cultural influence in Japan. Females on the streets of Tokyo were the bulk of interviewees, ranging from pre-teens to housewives. The most telling interviews were those explaining why they liked SNSD. The group’s allure—as stated by men and women of varying ages—stemmed from their beauty, slimness, long legs, expressive faces, style, and dancing/singing ability. They were skinny, pretty—the new “in” thing—and fans in their teens and 20s longed to be just like them.

And this longing has stimulated interest in other Korean products as well, such as food, clothing, cosmetics, and even technology. K-pop stars selling either Japanese or Korean products can have a real impact on consumer purchasing choices. In a recent article entitled “K-Pop stars lure Japanese consumers,” 53-year-old factory worker Yuko Ishii said it best: “I used to rule out Korean products, but now I have no problem with them. If my favorite star was advertising a South Korean TV, I would definitely buy it. I want to feel closer to them by buying the same products they use.” James Chung, a spokesman for Samsung in Seoul, said, “Most of Samsung’s customers in Japan are young people in their 20s and 30s. Their interest in Korean stars seems to be reflected in their purchases of our products.” Walk down the Korean strip in Tokyo, and you’ll see more of the same thing.

So, we can see the K-pop phenomenon is about fashion, beauty, and style, none of which is new to Japan. It can all be found in virtually every Japanese music genre. People commonly say that Japanese youth are most interested in what is cool, new, hip, and trendy; it’s not what the idols say, but how stylish they are when they say it. And the Korean music industry has been working very hard to market its talent toward this kind of crowd. K-pop producers train new talent for years; they select eager candidates based on looks and abilities, perfect their singing and dance performances, and then carefully control their careers. They may be even more “manufactured” than J-pop acts, and they are adored for it.

In the end, both the Japanese and Korean music industries are in it for the money (though what industry isn’t?). They focus on fashion and entertainment in the hopes of commercializing their product. With the aid of television, radio, and the internet, pop culture has been able to spread like wildfire, crossing language and cultural barriers to unite and excite countless fans around the globe.

Sure, the Hallyu Wave has triggered an anti-Korean response among some Japanese groups; and a few others simply resent the hoards of K-pop acts presently debuting in their country. But the discourse that’s begun between the two countries is certainly not regrettable. Artists like BoA and DBSK have shown Koreans and Japanese alike that amicability between the two cultures is indeed possible. While they may never become BFFs, it appears that they are, at the very least, hating on each other a little less.