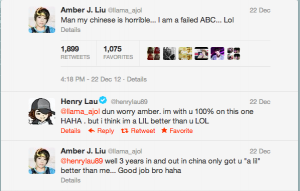

Back in September, Super Junior-M‘s Henry and f(x)‘s Amber created accounts on Weibo and became the newest addition to the handful of K-pop stars currently using the prominent Chinese microblogging service. Prior to showing up on the Weibo scene, both Amber and Henry used Twitter to communicate with their English-speaking fans. Though neither Henry nor Amber are fluent in written Chinese, the two of them have joined Weibo in an effort to connect with their Chinese-speaking fans in the same way that they’ve managed to connect with their English-speaking fans through Twitter. Henry and Amber use Weibo with the same, if not greater frequency that they do Twitter, despite the fact that 1) Weibo’s primary audience lies almost exclusively within China and other Chinese-speaking regions, while Twitter reaches a more global audience, and 2) Henry and Amber write in Chinese on Weibo even though they would probably be more comfortable using English on Twitter. For the record, Henry has 822,002 followers on Weibo and 999,214 followers on Twitter, while Amber has 812,818 followers on Weibo and 304,445 followers on Twitter.

Back in September, Super Junior-M‘s Henry and f(x)‘s Amber created accounts on Weibo and became the newest addition to the handful of K-pop stars currently using the prominent Chinese microblogging service. Prior to showing up on the Weibo scene, both Amber and Henry used Twitter to communicate with their English-speaking fans. Though neither Henry nor Amber are fluent in written Chinese, the two of them have joined Weibo in an effort to connect with their Chinese-speaking fans in the same way that they’ve managed to connect with their English-speaking fans through Twitter. Henry and Amber use Weibo with the same, if not greater frequency that they do Twitter, despite the fact that 1) Weibo’s primary audience lies almost exclusively within China and other Chinese-speaking regions, while Twitter reaches a more global audience, and 2) Henry and Amber write in Chinese on Weibo even though they would probably be more comfortable using English on Twitter. For the record, Henry has 822,002 followers on Weibo and 999,214 followers on Twitter, while Amber has 812,818 followers on Weibo and 304,445 followers on Twitter.

Henry and Amber are two of the few Chinese-Americans/Canadians (for ease of reference, the term “Chinese-American” will be used in this article to refer to second-generation Chinese-Americans and Canadians, though it is acknowledged that there are distinctions between the Chinese-American and Chinese-Canadian experiences) that are signed on as idols under Korean entertainment companies and are fairly well-known in both China and Korea. Even though the trajectories of Henry and Amber’s careers differ slightly from each other, it’s interesting to see how Chinese audiences have responded to these two young huaqiao and the complexity of their identities as Chinese-American K-pop stars. On the one hand, Henry and Amber are ethnically Chinese and grew up with Taiwanese and Teochew immigrant parents who bestowed their language and culture upon their children. At the same time, Henry and Amber spent the majority of their childhood and adolescence in North America; they speak English as their primary language and have adopted Western cultural and social practices as their own. Add to the mix the fact that both Henry and Amber are prominent faces within Hallyu — a phenomenon that has been widely embraced throughout the Chinese-speaking world but is still regarded as something distinctly Korean, and thus, foreign — and you’ve got an interesting dilemma for both Chinese K-pop fans and Chinese-American idol stars alike: what country or culture do Chinese-American stars like Henry and Amber belong to? Who gets to “claim” them as their own?

The advent of “Linsanity” opened up a milieu of discussion regarding Chinese-American identity in both the United States and China. Jeremy Lin’s parents emigrated from Taiwan to the United States in the 1970s, but the controversy that continues to brew within both Chinese and Taiwanese discussion circles is in regards to Lin’s ancestral connections to mainland China. Taiwan’s Han Chinese population is split primarily into two groups: benshengren, or Han Chinese who trace their ancestry to Fujianese migrants that settled in Taiwan during the 18th and 19th century; and waishengren, or Han Chinese who fled from mainland China to Taiwan with Chiang Kai-shek upon the Communist overthrow of the KMT in 1949. As many know, the dispute between China and Taiwan over the political sovereignty of Taiwan and the existence of a distinct Taiwanese cultural identity remains a topic of heated debate today, and the conflict over the “true” national identity of waishengren is one component of this debate. While Jeremy Lin’s father is a benshengren and can trace his lineage to the wave of Fujianese settlers from the 18th century, his mother is a waishengren whose grandmother emigrated from mainland China to Taiwan in the 1940s. Lin’s maternal waishengren lineage has sparked considerable debate between China and Taiwan over who gets to claim Jeremy Lin and “Linsanity” as their own.

The advent of “Linsanity” opened up a milieu of discussion regarding Chinese-American identity in both the United States and China. Jeremy Lin’s parents emigrated from Taiwan to the United States in the 1970s, but the controversy that continues to brew within both Chinese and Taiwanese discussion circles is in regards to Lin’s ancestral connections to mainland China. Taiwan’s Han Chinese population is split primarily into two groups: benshengren, or Han Chinese who trace their ancestry to Fujianese migrants that settled in Taiwan during the 18th and 19th century; and waishengren, or Han Chinese who fled from mainland China to Taiwan with Chiang Kai-shek upon the Communist overthrow of the KMT in 1949. As many know, the dispute between China and Taiwan over the political sovereignty of Taiwan and the existence of a distinct Taiwanese cultural identity remains a topic of heated debate today, and the conflict over the “true” national identity of waishengren is one component of this debate. While Jeremy Lin’s father is a benshengren and can trace his lineage to the wave of Fujianese settlers from the 18th century, his mother is a waishengren whose grandmother emigrated from mainland China to Taiwan in the 1940s. Lin’s maternal waishengren lineage has sparked considerable debate between China and Taiwan over who gets to claim Jeremy Lin and “Linsanity” as their own.

The conflict is understandable: it’s not often one sees a Chinese face gain worldwide recognition and fame, particularly in a field that isn’t stereotypically attached to Asian faces and reputations. The exact political, economic, nationalistic, and cultural reasons prompting Taiwan and China to fervently chase down Jeremy Lin and paint their respective flags on the back of his jersey are debatable. But at the very least, the Linsanity debate has sparked discussion amongst Chinese and Taiwanese audiences about the issues surrounding Chinese-American identity. In the past, many Chinese regarded Chinese-Americans simply as no different than those Chinese living in China, working under the assumption that overseas Chinese would band together in their new homes abroad and retain their culture and language in the same way that they would have back in China. However, the rising number of second-generation Chinese-Americans returning to the country of their parents for work or school is raising greater awareness in China in regards to what the Chinese-American experience is actually all about. Stark differences in language ability, social customs, and even physical appearance has prompted some to recognize the Chinese-American identity as distinct. But now, it seems as if neither Chinese people in China nor Chinese-Americans are really sure how to address the issue; all we’re really left with are variety show gags that poke fun at the way ABCs (American-born Chinese) speak Mandarin and occasional talk-show panels that superficially gloss over the “culture shock” that Chinese-Americans undergo in China or Taiwan.

But even though Amber and Henry are two of the most prominent Chinese-Americans working in the Mandarin-speaking entertainment market right now, there’s very little acknowledgement of their identities as Americans and Canadians, period. Variety show hosts in Taiwan introduce Henry as being “Taiwan’s Pride” despite the fact that he’s actually only half-Taiwanese. It’s not as if the subject of cross-cultural exchange is too intense for your typical episode of 100% Entertainment; in fact, it almost seems too easy for variety show hosts in Taiwan or China to make Amber or Henry’s “Americanness” a running gag of sorts. But it seems that China and Taiwan are more comfortable with emphasizing the “Chinese” side of Amber and Henry’s identity as Chinese-Americans while forgoing the fact that, in terms of culture and language, Henry and Amber are as American as it gets.

However, this probably isn’t a result of China and Taiwan’s unwillingness to address Chinese-American issues as much as it is a matter of acting out of habit. Rochester-born Wang Lee-hom is one of the hottest stars in the Mandopop market, and even though he is just as “American” as Henry or Amber, his near-native fluency in Mandarin as well as his familiarity with Chinese social customs and values assimilates him perfectly into the Chinese entertainment scene as some that is “just as Chinese” as his target audience in China and Taiwan. EXO-M‘s Kris is regarded in a similar manner; it’s almost as if every variety show host in China has completely forgotten the fact that Kris spent a considerable amount of his youth in Vancouver and simply identifies him as the boy from Guangzhou — a task that is made easy by his perfect Mandarin and awareness of Chinese culture and society. But while this treatment may work just fine for Wang Lee-hom and Kris, it’s not a one-size-fits-all deal. The Chinese-American experience is incredibly varied, and Wang Lee-hom’s identity as a Chinese-American takes a drastically different form than that of Kris’ than that of Henry’s than that of Amber’s, and so on.

However, this probably isn’t a result of China and Taiwan’s unwillingness to address Chinese-American issues as much as it is a matter of acting out of habit. Rochester-born Wang Lee-hom is one of the hottest stars in the Mandopop market, and even though he is just as “American” as Henry or Amber, his near-native fluency in Mandarin as well as his familiarity with Chinese social customs and values assimilates him perfectly into the Chinese entertainment scene as some that is “just as Chinese” as his target audience in China and Taiwan. EXO-M‘s Kris is regarded in a similar manner; it’s almost as if every variety show host in China has completely forgotten the fact that Kris spent a considerable amount of his youth in Vancouver and simply identifies him as the boy from Guangzhou — a task that is made easy by his perfect Mandarin and awareness of Chinese culture and society. But while this treatment may work just fine for Wang Lee-hom and Kris, it’s not a one-size-fits-all deal. The Chinese-American experience is incredibly varied, and Wang Lee-hom’s identity as a Chinese-American takes a drastically different form than that of Kris’ than that of Henry’s than that of Amber’s, and so on.

But as far as marketing goes, it’s not a bad idea to play off Chinese-American stars as being “fully Chinese” even if their Mandarin is imperfect and they lack knowledge on Chinese social customs. After all, there’s a good chance that Henry’s popularity in Taiwan is due to the fact that Henry is marketed as the “Taiwanese” member. On the other hand, Zhou Mi is consistently introduced on Taiwanese variety shows as “the friend from the mainland” and has notably less popularity in Taiwan despite being the only other member in Super Junior-M who can speak Mandarin. Almost all of Super Junior-M and f(x)’s overseas promotions are concentrated in Asia, and while there is virtually no viable Chinese-American market demographic in Asia, there certainly is a Chinese market demographic. Thus, it would make sense to market Chinese-American stars as being as relatable to the local target demographic as possible; that is, as Chinese and as un-American as possible. But at the same time, one wonders how Chinese-American idols like Henry and Amber cope with the fact that their national and cultural identity is entirely contingent upon which country they’re promoting in.

This especially holds true for Amber, who spends far more time promoting in Korea than she does in China and is presently the only Chinese-American doing work full-time in Korea as a mainstream K-pop idol. If anything, it seems as if the K-pop variety scene isn’t really sure what to make of Amber apart from the fact that she can speak English. Because Amber’s identity is so difficult to define, it’s almost as if she needs to be “as Korean as possible” in order for her career in Korea to survive. To an extent, the same could be said of any other non-Korean K-pop star, but idols like Victoria, Hangeng (during his time in Super Junior), and the entirety of EXO-M still have the privilege of holding legitimate promotions on their own home turf. Similarly, Korean-American K-pop stars like Tiffany, Jessica, and Krystal are practically regarded as “native” Koreans instead of Korean-Americans by sheer merit of their common Korean ethnicity. Even Jay Park — who, unlike most Korean-American K-pop stars, is a third-generation Korean-American who didn’t speak any Korean growing up in the States and has the burden of the whole “Korea is gay” Myspace debacle to his name — is now seen as being just as Korean as any Kim Chul-soo living down the block in Seoul. Chinese-Americans, then, are the only group of “foreigners” in K-pop who are unable to work anywhere that they can call home, and, as a result, must adopt an identity that is not fully theirs in order to fit in and be accepted by their consumer market.

This especially holds true for Amber, who spends far more time promoting in Korea than she does in China and is presently the only Chinese-American doing work full-time in Korea as a mainstream K-pop idol. If anything, it seems as if the K-pop variety scene isn’t really sure what to make of Amber apart from the fact that she can speak English. Because Amber’s identity is so difficult to define, it’s almost as if she needs to be “as Korean as possible” in order for her career in Korea to survive. To an extent, the same could be said of any other non-Korean K-pop star, but idols like Victoria, Hangeng (during his time in Super Junior), and the entirety of EXO-M still have the privilege of holding legitimate promotions on their own home turf. Similarly, Korean-American K-pop stars like Tiffany, Jessica, and Krystal are practically regarded as “native” Koreans instead of Korean-Americans by sheer merit of their common Korean ethnicity. Even Jay Park — who, unlike most Korean-American K-pop stars, is a third-generation Korean-American who didn’t speak any Korean growing up in the States and has the burden of the whole “Korea is gay” Myspace debacle to his name — is now seen as being just as Korean as any Kim Chul-soo living down the block in Seoul. Chinese-Americans, then, are the only group of “foreigners” in K-pop who are unable to work anywhere that they can call home, and, as a result, must adopt an identity that is not fully theirs in order to fit in and be accepted by their consumer market.

A while ago, I wrote a piece on Asian-American K-pop stars and the way in which debuting in Korea is becoming another way for Asian-American pop star-hopefuls to gain the fame and recognition that, as a result of racism and negative stereotyping, has become nearly impossible for East Asians to achieve in Western entertainment spheres. For the most part, Korean-American K-pop stars like G.NA and Ailee have been well-received by Korean audiences as “one of their own,” and their images in Korea have been inextricably tied to their identities as Korean rather than American. However, this doesn’t mean that entertainment companies value Korean-American recruits above any other Asian-American recruit. Chinese-American trainees are particularly valuable due to their potential marketability amongst Mandarin-speaking audiences, and it’s not unreasonable to think that entertainment companies with a serious intent on pursuing the Chinese or Taiwanese market will begin to make greater investments in Chinese-American trainees. At the same time, K-pop’s continuing popularity in Asian-American social circles aids in fostering pop star dreams in the form of K-pop idoldom within young Asian-Americans — a phenomenon that is easily illustrated by the immense amount of Asian-Americans that show up to global auditions held in the United States and Canada.

Then again, Henry and Amber are probably too busy with their own careers to angst over the lack of acknowledgement of their Chinese-American identities — and to be perfectly honest, they’re probably better off that way. At the same time, however, it’s impotant to note that there is a growing level of awareness in China and Taiwan in regards to Chinese-American issues, and Chinese-American celebrities such as Henry and Amber are living examples of an issue that is still fairly abstract and conceptual for many Chinese and Taiwanese who lack knowledge about multiculturalism or the social effects of ethnic diaspora. As Super Junior-M embarks on full-time promotions in China and Taiwan for their new album and f(x) continues with domestic and overseas promotions throughout the year, it’ll be interesting to see how the evolving views of Chinese-Americans in Chinese society will be reflected in Henry and Amber’s activities as idols.

(New York Times, CIA World Factbook; images via GQ, Men’s Uno, Sina, 3rdwavemusic@twitter)