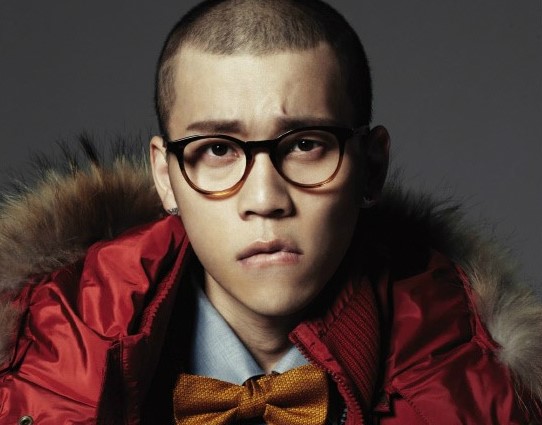

Ulala Session, the contestants of Superstar K3, never made a big secret out of Yun-taek’s health problems, having revealed he suffers from stomach cancer. They progressed on the show, got to the final and won the big prize, with their victory being naturally succeeded by official promotions. So what’s with the old news? Well, it seems that some fans doubt the truth of his illness, claiming Yun-taek has shown to be too joyful during performances and accusing him of falsehood.

Following the restless netizens’ rumble, Yun-taek has publicly brought his doctor on SBS’ One Night in TV Entertainment to persuade his audience he is indeed suffering from a terminal illness. To which people were still skeptical. The only sane phrase that was said in this “scandal” is Yun-taek’s statement:

I think it’s strange that I have to explain it is true that I’m sick.

It’s hard to keep a straight face while writing this. It’s also hard to define the behavior of these… people(?). No word goes low enough. Despicable? Ridiculous? Out of their mind? They appear to be stripped of any sense of humanity: everything is just a show. According to them, Yun-taek should faint constantly on stage, never smile and feel miserably just for their entertainment, with maybe a dramatic hospitalization to top it off. At first, I just tossed them in the psycho section; at a second thought, they provide an interesting analysis basis. When do these unique individuals stray from the average K-pop fan into serious contenders for a mental facility’s clientele?

The contemptible part of the story lies in their refuse to acknowledge a basic sound judgement: they talk about a person’s existence. Instead, they focus on the idol’s life. While I wouldn’t include Ulala Session in the idol category, it’s exactly how they treat him. We usually forget what connotations this term holds: it’s not associated with other words like “hero” or “god” for no reason. The media outlets feed us with personae, a mishmash of someone’s personality and the mask they’re putting on as public figures.  The spectator interprets one’s gestures, sayings, attitude just as he or she does when establishing a normal social relationship, skipping the reciprocity of bonding. The result is the dual role of para-social interaction: on one side, like any kind of human interaction, a person receives and decodes signals while experiencing a positive/negative feeling towards another person; on the other hand, the one-sided nature of the relationship and the utter absence of the “idol” from the other participant’s reality leads to its conversion into an intangible, human-surrogate product. This interplay causes numerous contradictions: it is both personal and impersonal, both real and fake, both human and dehumanized.

The spectator interprets one’s gestures, sayings, attitude just as he or she does when establishing a normal social relationship, skipping the reciprocity of bonding. The result is the dual role of para-social interaction: on one side, like any kind of human interaction, a person receives and decodes signals while experiencing a positive/negative feeling towards another person; on the other hand, the one-sided nature of the relationship and the utter absence of the “idol” from the other participant’s reality leads to its conversion into an intangible, human-surrogate product. This interplay causes numerous contradictions: it is both personal and impersonal, both real and fake, both human and dehumanized.

You can add the strategy Mnet used to speculate Yun-taek’s case to its fullest. Their songs choice or any chance the leader got to communicate with his audience had to bring up his condition. Probably sadder than the netizens’ comments was their strategy to transform one’s personal turmoil and maybe tragic situation into a selling point. When Ulala Session won, news publications focused more on the astonishing victory of a person with terminal disease, and less on the role the musicians could play on the Korean music scene. The reason behind it is the same: the viewers don’t fully distinguish where the artist ends and the person begins. If the actor has the benefit of quitting a role once he leaves the theater, the idoldom doesn’t offer this privilege. Anything professional and — even better — personal is subject to public interest. The entertainment industry jumps on every occasion to profit a bit more and couldn’t care less for ethics.

But does the public care more? The average media consumers, integrating a big chunk of us too, is completely desensitized: nothing surprises them and something as horrendous as Yun-taek’s case has to happen to make some of us tick. Whenever our life gets boring or grey-ish, we turn to news and gossip to increase our low blood pressure. Next to literature, cinematography or more generally, art, the tabloids’ universe has become the new source of fiction. We grab our popcorn, watch the drama unfold and review it as we do with movies.

An additional layer K-pop overlaps consists in the influence of netizens. Yun-taek felt the need to address these rumors, while it would have been maybe better for him to ignore them and let his so-called fans go on with their chit-chat. The latter option though rarely happens. Controversies are quickly answered and more than often, the entertainers’ superiors, their companies — which have the power, more than anyone, to regulate the dimension of scandals — force them to do so. Abiding to their customers’ will and warranting them concessions when it comes to idols’ private lives or personalities pushes the para-social relations into a dangerous zone, where the rule-setter is no longer the initiator (the celebrity), but the one on the receiving end (the aggregate of fans who indulge in the illusion of intimacy). Yun-taek, after being asked several times about his disease, was surprised how viewers were determined to pity him, despite his optimism:

My doctor thinks it’s sad that people think I am so sick when I am actually really healthy.

The overaggressive reaction proves voters had expectations: they invested their mercy into making Ulala Session the winner and when they found the foundation for their acts was dubious, they asked for a clarification just about the same way you ask for a refund. Dealing with a sensitive issue, respect for people’s privacy and the reevaluation of their function or status never reached their conscience. Yun-taek has a debt, a role to perform and he better do it right.

Of course, there are levels and it’s impossible for celebrities to avoid this kind of communication. While there is no universal cure or a possible remedy for the way things go, a doze of sanity would be welcome. Being a public person comes with the social ordeal, but limits, as blurry as they might get, exist. If we were quick to jump at the thought of people playing with the notion of cancer, is because we’re aware when anyone pushes the unspoken barriers. If this served to anything, it was probably a bitter lesson for fans in general to take a step back from time to time and sweeten their tone. What are your thoughts on this one, guys? What would you like to add or change?

(Horton, Donald and Richard Wohl – Observations of Intimacy at a Distance, Watkins, Daffyd – Horton and Wohl’s Concept of Para-social Interaction, Yahoo, Reuters, Nate, Korea Times, Sports Seoul, Tistory, Nemesys)