Anyone familiar with Kpop is familiar with aegyo. Hard to define but easy to spot, most fans have a love/hate relationship with this childlike attribute (characteristic/action/attitude/behavior).

So, what’s this aegyo all about? And why are Koreans so hot for it?

Korea’s general obsession with cuteness stems from Japan’s Kawaii craze that spread across Asia like wildfire back in the ‘90s. In fact, aegyo girls are reminiscent of anime/manga characters (as are aegyo boys), and have the same kind of appeal. Yet, Koreans have made this “cute” concept their own, and the main difference might lie in their focus on the “oppa.”

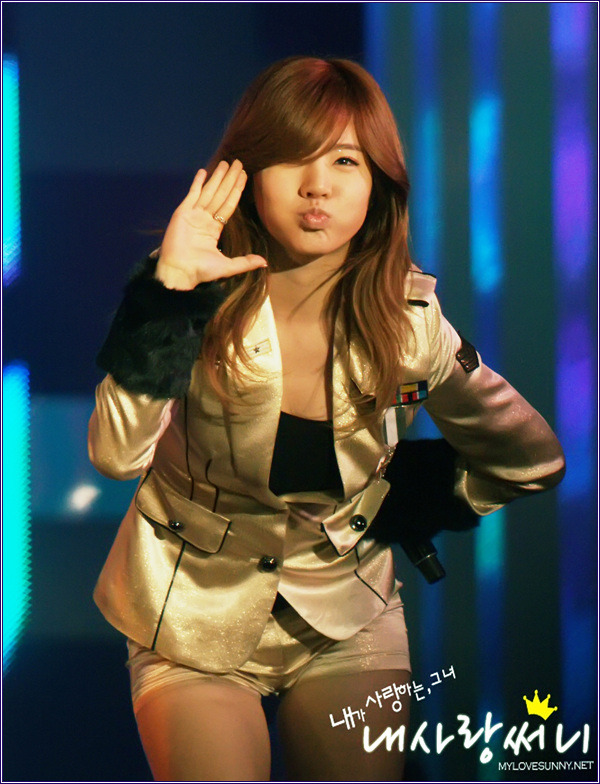

Kang In-kyu examines the “rise of the oppa” as expressed through Kpop’s girl groups (a translation of which can be found here), for aegyo is ultimately intended for the oppa—to both attract and to please the oppa (see a clip of SNSD’s Sunny’s aegyo to see it’s “power”). Kang attempts to explain why this phenomenon appeared in Kpop ( relating it to the rise of the Lolicon characters in Japan) and how this “oppa craze” has halted any advancement in gender equality in Korean society. Essentially, in Kang’s view, aegyo and its service to the oppa has made women easily conquerable: aegyo—while adorable (at times)—makes girls dependent, submissive, childlike.

And powerless, since a girl being/using aegyo cannot also express assertiveness or independence. While aegyo may help a woman sway the men in her life, she cannot then proceed without their approval. She may say “Oppa, please!” but if he denies her, she can plead and throw a tantrum but she cannot defy him. For like a child, it is the adult who has the last word.

Yet, for most critics their issue with aegyo and its association with the oppa has greater implications than just power struggles in a relationship. For, while ajosshi may say their interest in girl groups is based solely on paternal and avuncular feelings, anyone who has seen SNSD knows that they don’t wear what they do for nothing.

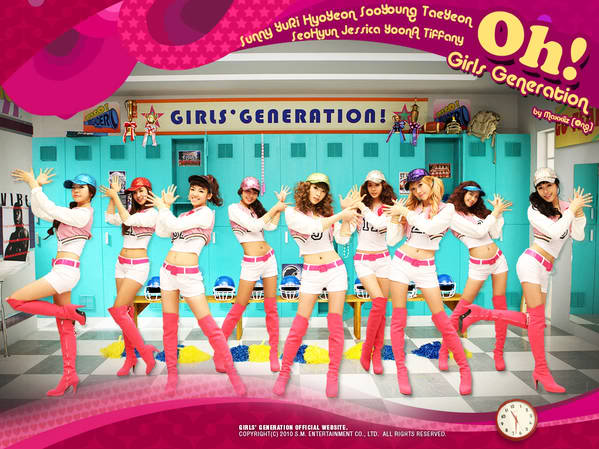

Female acts are increasingly filled with members who appear adolescent in nature, and don revealing (yet childish) outfits, all which is blatantly intended to stir sexual arousal in men. The MV for SNSD’s Oh! is a great example of this, where their excessive aegyo, and skimpy yet “cute” high school-spirit wardrobe, is directed towards their oppa (read: their ajooshi fans).

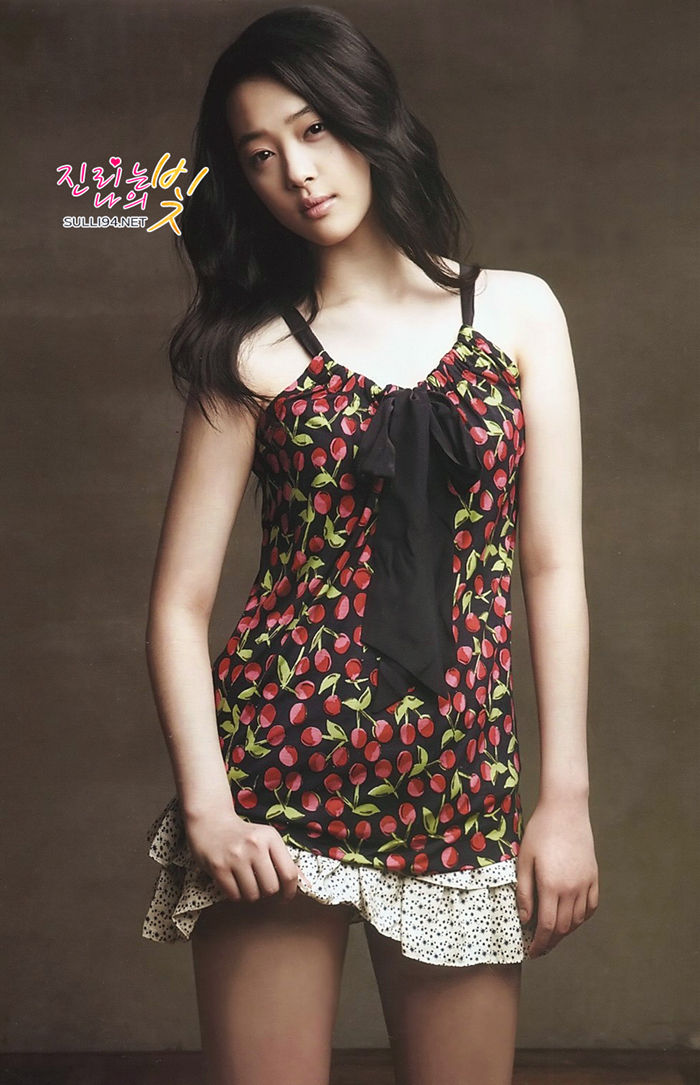

This may not seem controversial or problematic when the idols are older girls, but it can be a bit unnerving when they are much younger. For instance, check out the Oh Boy! Magazine photoshoot for f(x)’s youngest member, then-15-year-old Sulli, who, as of 2010 was said to have the most ajooshi fans of the group. The lack of makeup enhances her youthful innocence while the amount of leg shown (plus the skirt-lift) seems quite suggestive, perhaps verging on pedophilia.

The use of aegyo, and the image of youth in the media, is in the hands of men. Men control the industry. Men choose the idols, assemble the groups, and decide at what age to put these children in the public eye, wearing clothing that may or may not match the girls’ (sexual, emotional, or psychological) maturity levels. Some may argue that this sexualization isn’t an issue. So what if men ogle young teens? So what if older men are sexually aroused by children?

It’s complicated.

We’ll ignore Korea’s teen prostitution problem for now, and the fact that sex is so taboo that there’s a terrible lack of sex education in Korean schools. This repression is obvious, as any Kpop and Kdrama fan can tell you, because god forbid anything overtly sexual be presented on public television. Basically, they pretend that sexual desire doesn’t exist.

Which just screws up society’s mental state even more.

This is why ajooshi must claim that their attraction to girl groups is purely familial in nature. If older men were to admit they really liked watching SNSD dance to Gee in their short-shorts because they secretly wanted to screw each and every member, they’d be called perverts and seen as disturbed sexual deviants.

Korean music columnist Kim Bong-hyeon sums this up beautifully in his article entitled, “Is it a Sin to Like Girls’ Generation Because They’re Sexy? (or The Confession of an Average Korean Man)” (read the full translated article here):

…It was with their song Gee that Girls’ Generation really started appearing sexy to me; before that, they were merely like little sisters. But then they started wearing tight, clinging croptops and jeans, and the girls had changed to women.

…The important point here is not how sexy they are…Rather, that despite their innocent expressions, Girls’ Generation’s clothes, accessories and lyrics are all designed to provoke men into having sexual fantasies about them. But this leaves me feeling a little perturbed and guilty: how can I think like that when I see those angelic faces? Am I a pervert?

…While deliberately being sexy, Girls’ Generation pretend that they aren’t. Which proves to be even sexier than if they just admitted it, for every man’s instinct is to have a woman who is a wise mother and good, virtuous wife by day, but a shameless hussy at night.

…The first thing to worry about is the question of if desire is a bad thing. Or to be more precise, is getting sexually stimulated bad when that is the deliberate and expected reaction? Does the fact that it is done indirectly and stealthily mean that we have to pretend that we don’t feel aroused? Isn’t that being dishonest and deceiving yourself? We all know that as long as it doesn’t cause harm to others, honesty is a virtue. And surely it is worse to so insidiously arouse men than to feel aroused. Why on Earth was I feeling guilty about this? This is not a problem with myself, but more a systematic thing.

…So although I admit to the fact that Girls’ Generation arouses me, at the same time I worry that I am just being manipulated by their company. Or in other words, while I am unceasingly aroused by them at the same time I think seriously about if both that and what the company is doing is correct and appropriate.

As a result, I realize there are many problems to Girls’ Generation being sexy while pretending not to. First, while it is undoubtedly a very effective strategy for the company to make money, to society it reaffirms that there is a public and private face to put on sex. For while the group is designed to stimulate men’s sexual fantasies, they can not admit to this. Rather than expressions of sexual liberation, they must instead have guilt about how differently they feel inside and what they must actually say. This is why you have men like me saying that sexiness is something else entirely.

This confession, while daring in its honesty, reveals a part of Korean society that the government and media leaders try desperately to keep hidden. It gives us a clearer picture of the culture that created the Kpop machine, and the perceptions of those who control, work within it, and consume it. While we may never fully grasp these complex social issues on a personal level, being aware of these contradictions and how they came about can help Western fans and critics alike better understand and appreciate the nuance and struggle that exists in the Korean entertainment industry, and how this both reflects and influences Korean society today.