Education is a serious business in Korea. The Suneung (College Scholastic Ability Test (CSAT)) takes place yearly, with 2021’s round happening just a month ago. Each time, it leaves us wondering: why is there a serious fixation on tests and grades in Korea? How do youths really feel about this notoriously exhausting yet critical examination? And more interestingly, how does K-pop reflect this issue?

University is a big deal. The Suneung is treated as a determiner of one’s life at the ripe age of 18. As many exam takers have admitted, it is not uncommon to hear that this one day will determine one’s entire life and if they fail their Suneung, they are doomed for life. Naturally, there is a lot of pressure to do well to not only enter university but the highly prestigious SKY universities. Similarly, as Asian Boss confirms, “In Korea, the university you attend is regarded by society as one of the most important factors for determining your success in life” as a bright future is promised upon entering any of the country’s top three universities.

But why so? Digging deeper, academic success is important as it is the main driver of social mobility. In having to revolve their life around academia, the whole family invests heavily in their children’s education, with some parents turning to rituals like hiking to the mountains to pray for good results. As one can tell, Suneung is not only a serious business — it is often also a family business. Parents invest and even over-invest in their children to send them to the best hagwon (cram school) all for a shot at a better future. Unfortunately, good results are not always yielded. Those who fail retake the exam for years on end until they achieve their desired results. At other times, being a college graduate does not guarantee a job.

Needless to say, this cutthroat competition has some long term effects on the country’s youth. For one, it further deepens its ongoing youth unemployment crisis, where a record high of 27% of youths aged 15 to 29 remains unemployed. This severe problem of overeducation and underemployment is broadly due to Korea’s hyper-fixation on grades, honouring only the SKY universities, and its “overprotection of top-tier jobs and education fervour that produced a flood of people wanting only that small number of top jobs”. In other words, the imbalance between supply and demand in the market creates a serious bottleneck situation.

An equally severe consequence of Suneung is the reliance on rote memorization where Suneung prepares students to be test-takers rather than creative or critical thinkers. The most prevalent example of this is Korea’s notoriously difficult English exam, where even native speakers struggle with. Many have regarded this exam as impractical and simply too difficult for non-native speakers. In teaching students to “solve” questions and pick the right answer instead of understanding the questions, learning English then becomes counterproductive.

At the end of the day, what do students get out of this? Admittedly, though there is some good that emerges from this intense competition, the cons far outweigh the pros. The cons were notoriously reflected in SKY Castle, where it touched the rawest of nerves in its representation of the rigorous nature of Korea’s education system. But what about K-pop’s reaction to this? As people in the same age bracket, many artists do address the elephant in the room: the societal pressure to succeed, for only success, is recognised. What then emerges out of this are songs about running away, rebellion, and entrapment, all while criticizing the strenuous education system.

In a short amount of time, not only have TXT proven their abilities as forerunners of the fourth generation, their music resonates heavily with the younger half of youths. Notably, while the whimsical “9 and Three Quarters” speaks of friendship and imagination, it also addresses the pressure of education and its mind-numbing effects. Unfortunately for many, this is their reality where they long to run away to another world void of these worries.

In “9 and Three Quarters”, despite TXT dressed in their school uniform, they are anywhere but studying. There’s Yeonjun cutting up a book, Soobin aimlessly drawing on the blackboard, Taehyun and Huening Kai in a daze, and Beomgyu finds himself in the field. What seems like a simple characterisation of the members tells a more complex narrative about the repressive nature of schools. That is, unlike the world of Harry Potter, TXT’s school is not one where they can freely express themselves.

Of course, the track is a clear reference to Harry Potter. But a closer inspection reveals TXT’s clever use of this fictional reference to show the contrast between the fictional yet creative world of Hogwarts and their reality, which is quite the opposite. That being said, through referencing Harry Potter, TXT criticizes the rigid nature of Korea’s education system where creativity and imagination are discouraged while rote learning and obedience are encouraged. In fact, it is no secret that schools place more emphasis on subjects that are taught through rote learning, while placing less emphasis on creative subjects such as the arts.

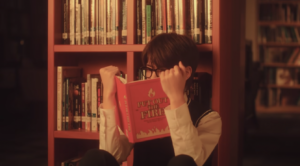

Reflecting their desperation to rebel against the system, one recurring motif throughout is TXT’s symbolic use of fire. Upon nightfall, TXT secretly reads in the library, a place of imagination and fantasy, while a fire is burning nearby. The act of reading outside of what is necessary is then portrayed as corrupted and catastrophic. Though they are aware of its destructiveness, they remain unbothered as they seem to enjoy being able to dive into their imagination through reading.

Yet, even reading cannot save them from growing restless. To feed their boredom, school, the same source of youths’ stress, becomes a playground when they turn to magic to run away into their imagination, wanting their “dreams [to] become reality”. While this paints a brighter picture of youths where they can have fun anywhere, it still reveals a grim truth: young Koreans can never break free from the chains of the cutthroat education system.

Throughout the MV, TXT are confined within the bounds of their school. Though they explore the school to enter a new dimension, their secret hideout still remains within the school compounds. After all, imagination is all but a temporary relief as “9 and Three Quarters” leaves an open ending with what looks like TXT walking back to reality.

Needless to say, TXT echoes what their seniors, BTS, stand for in “N.O”. “N.O” is a powerful and even daresay, a revolutionary song that still resonates with many eight years after its release. Yet, while relatable, it simultaneously exposes the unchanging nature of an education system led by unhealthy competition.

In “N.O”, BTS address the problems of education and the disconnect between what youths want and what adults force upon them. There is simply no room for failure, as Suga explains, “It’s either number one or a failure”. Students are not only expected to be achievers but overachievers and they have no choice but to partake in the rat race.

BTS go on to critique the grade-conscious society where society pins the definition of ‘success’ entirely on the CSAT. Or in Suga’s words, youths are made to be “study machines” to meet their parents’ expectations of matriculating into the SKY universities to be able to succeed later in life, defined by having “a good house” and “a good car”. In turn, students feel trapped as education is suffocating. And parental pressure increases it twofold as they become “puppets” of their parents.

Moreover, Korea’s fixation on ‘specs’ (meaning qualifications or experiences that will bulk up one’s resume) leaves students with no time to even dream. As Jungkook laments, “Dream is gone, no time to breathe. School, house and PC room is all we have”. And as J-hope echos, “I want to eat and have fun, I want to tear my uniform”.

Both Jungkook and J-hope don’t have the time, or more accurately, aren’t allowed time to dream and play as normal teenagers should. J-hope proceeds to compare the act of studying to a “factory” of “continuous cycles”, with only one way in and one way out, which is academic success. In other words, bright-eyed youths are trapped in an endless cycle of competition and parental expectations, where it even encourages teens to turn their backs on one another. As Suga critiques, “Who do you think is the one who makes us step on even our close friends to climb up?”.

Visually, BTS find themselves in a white classroom where the only colours present are white, black, and red. They move in unison like mechanized robots, void of thoughts and individuality. Sans the only red in the room, the red rectangle painted on the headmaster’s face, the room is essentially black and white. Like “9 and Three Quarters”, this reflects society’s stifling of creativity and freedom, further adding on to their unhappiness. Tired of this endless cycle of stress, BTS rebel against the system through “N.O”. And in turn, they encourage other young people to break the cycle in their own ways.

Everybody say NO!

It’s not going to work anymore

Don’t be captured in others dreams

Though arguably, BTS popularized the concept of youth rebellion, it is not entirely new. As evergreen as it is, its existence traces back as far as to Seo Taiji and Boys’ “Come Back Home” and “Classroom Idea”. Naturally, BTS’s “N.O” share the same sentiments as “Classroom Idea”. Seo Taiji and Boys use “Classroom Idea” not only to criticize Korea’s hyperfocus on education, but also a system that leaves no room for creativity and individuality. As Thompson suggests in The Strengths and Weaknesses of the Korean Education System: An Insider’s Perspective,

It seems that many parents understand and agree that public schools must sacrifice creativity and skills-based education in order to focus on test-taking skills and the rote learning that produces better test scores.

In the same vein, Seo Taiji and Boys comment on the suffocating nature of the education system:

Completely stuck, stuck in all directions, you are stuck and suddenly, we all accept it

It’s such a shame that I have to spend my youth only in this dark classroom

Though education is believed to open one’s mind by improving life through social mobility, it produces the opposite effect here. The trio speaks of the mind-numbing and close-minded effects of education, where students sit dreadfully, hours on end, in a “dark classroom”. In a wider scheme of things, unfortunately, young Koreans have no choice but to spend their fleeting moments studying, only in faint hopes of improving their socioeconomic status. In doing so, Korea’s creation of test-ready students fosters “production, performance and obedience”, while equally important traits such as critical thinking and creativity remain underdeveloped.

With a system that fuels stressful competition, there is no happy ending for everyone. As the band points out what Suga reiterates in “N.O”, “Everybody steps on each others’ heads and climbs up to be able to become superior”. Education then becomes brutal where social skills are secondary while achieving academic success is primary.

In light of Korea’s education fever, it is equal parts reassuring and worrying that K-pop addresses these serious consequences that youths continue to face. With these problems finding their roots back to the 90s with “Classroom Idea”, it pains to say that not much has changed over time. Though youths are rebelling in their own ways, it goes beyond the power of youths to change the system.

What then remains of the future of many Korean youths? With the education craze only getting worse as unemployment numbers rise, students have no choice but to participate in this endless cycle. With little to no alternatives left to survive, one aspiring accountant confesses, “All these tests, and memorizing the right answers,[…] I sometimes wonder if this is really the only way to succeed”.

(Bloomberg. Social Science Space. Reuters. Tim Thompson. The Atlantic. The New York Times[1][2]. The Korean Herald[1][2][3]. The Straits Times. NPR. Your University Guide. YouTube[1][2][3]. Images via Big Hit Entertainment, Los Angeles Times, The Straits Times. Lyrics via Genius[1][2], Readable.)