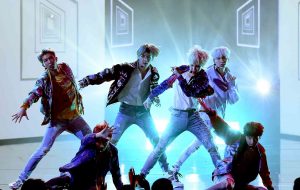

When BTS took to the stage at the American Music Awards for their US television debut, they set a precedent not only as a Korean boyband making waves in mainstream American media, but showcased South Korea’s growing hip hop scene to international audiences. And although RM’s rapping or Jimin’s sparkly jacket may have caught your attention, as the chorus of “DNA” ended and the beat kicked-in, J-Hope and Jungkook dropped to the floor to simultaneously execute a simple knee slide and kick out – performing breakdance moves at an awards show largely dedicated to mainstream pop.

When BTS took to the stage at the American Music Awards for their US television debut, they set a precedent not only as a Korean boyband making waves in mainstream American media, but showcased South Korea’s growing hip hop scene to international audiences. And although RM’s rapping or Jimin’s sparkly jacket may have caught your attention, as the chorus of “DNA” ended and the beat kicked-in, J-Hope and Jungkook dropped to the floor to simultaneously execute a simple knee slide and kick out – performing breakdance moves at an awards show largely dedicated to mainstream pop.

This is significant, as it demonstrates the way breakdance has become so ingrained in South Korean hip hop culture that it has converged with K-pop. Suga, J-Hope and Jungkook are just three of the many idols who trained as b-boys on their way to making it in the K-pop industry. And as BTS’ popularity grows, the roots of their hip hop influenced performances reveal the way Seoul’s burgeoning breakdance scene has impacted Korean pop culture. Like K-pop, this dance movement has been co-opted by commercial and governmental interests to boost the nation’s economy, and the success of Korean b-boys in the high-stakes world of international breakdance battles echoes the way K-pop has become ubiquitous through the drive of its performers.

Breaking, more commonly known as breakdance, was first founded in the 1970s by young African-American and Puerto Rican dancers at the Bronx parties held by DJ Kool Herc, one of hip hop’s founding fathers. As DJs lengthened the break beats on records, dancers began to experiment, drawing influence in equal part from James Brown, martial arts movies and acrobatics. The Zulu Kings are credited as the original first generation breakdance crew, founded by Afrika Bambaataa, as a way for street gangs to face-off through dance battles rather than fights. Members of the Zulu Kings went on to form Rock Steady, the crew that captured the attention of mainstream media and performed in movies such as Wild Style, Flashdance and Beat Street in the early 1980s.

Breaking, more commonly known as breakdance, was first founded in the 1970s by young African-American and Puerto Rican dancers at the Bronx parties held by DJ Kool Herc, one of hip hop’s founding fathers. As DJs lengthened the break beats on records, dancers began to experiment, drawing influence in equal part from James Brown, martial arts movies and acrobatics. The Zulu Kings are credited as the original first generation breakdance crew, founded by Afrika Bambaataa, as a way for street gangs to face-off through dance battles rather than fights. Members of the Zulu Kings went on to form Rock Steady, the crew that captured the attention of mainstream media and performed in movies such as Wild Style, Flashdance and Beat Street in the early 1980s.

Through these films and word-of-mouth spread by American soldiers stationed in Itaewon, breakdance travelled from the streets of New York to South Korea’s club scene. But the movement didn’t truly begin until 1997, when Korean-American hip hop enthusiast Justin Jay Chon gave a VHS recording of the LA Radiotron breakdance battle to the budding Expression Crew in Seoul. The tape was copied multiple times and passed from dancer to dancer, inspiring the foundation for breakdance in South Korea. Just five years later, the Expression Crew won two of the most prestigious international breakdance competitions: Battle of the Year and the UK B-Boy Championships.

Since then, Korean b-boys have become a force to be reckoned with on the global breakdance scene. Some of the top crews in the world hail from Seoul, including Rivers, Jinjo, Drifterz and Morning of Owl, and have claimed multiple titles at top global battles such as Red Bull BC One, Freestyle Session, and the R-16 Korea World Final. As a mark of respect acknowledging South Korea’s impact on the development of breakdance, three members of the Rivers crew have become affiliates of the original Zulu Kings.

Yet no Korean b-boy has built a greater legacy than Hong 10. A member of the Expression Crew, who claimed Korea’s first breakdance title, Hong 10 has also represented the Drifterz and Jinjo, achieving multiple wins at six of the nine most prestigious international breakdance competitions. He is credited with several signature moves including switching halos, chair flares and is known as the king of halo freezes, for the multiple variations he has created. His legacy is such that he was even named-checked in Epik High’s track “Rock Steady”.

https://youtu.be/BsjYKnU_yNc

The success of Korean breakdancers has been largely attributed to two key factors. First, Korean dancers are known for executing daring, dynamic power moves to pull off technically impressive performances. Breakdance can be approached from two distinct angles — one is to focus on footwork, the original moves that allow a dancer to showcase their unique style and innovation by demonstrating different variations. Alternatively, b-boys and b-girls can prove their physical strength, stamina and athletic ability by performing acrobatic power moves such as headspins and windmills. These are the moves Korean b-boys have, by and large, taken to the next level and dedicated their focus to perfecting. This has enabled them to arguably become technically better than many American b-boys who have the ability to execute basic power moves, like the majority of dancers at the pro level, but generally prefer to demonstrate their flair through footwork and style. It is a common point of contention at international battles over which aspect a b-boy should primarily be judged on. However, the Korean dedication to reaching higher levels of prowess in power has in part contributed to the success of many crews, who are subsequently capable of more dynamic performances, simply pulling off moves nobody else can.

The success of Korean breakdancers has been largely attributed to two key factors. First, Korean dancers are known for executing daring, dynamic power moves to pull off technically impressive performances. Breakdance can be approached from two distinct angles — one is to focus on footwork, the original moves that allow a dancer to showcase their unique style and innovation by demonstrating different variations. Alternatively, b-boys and b-girls can prove their physical strength, stamina and athletic ability by performing acrobatic power moves such as headspins and windmills. These are the moves Korean b-boys have, by and large, taken to the next level and dedicated their focus to perfecting. This has enabled them to arguably become technically better than many American b-boys who have the ability to execute basic power moves, like the majority of dancers at the pro level, but generally prefer to demonstrate their flair through footwork and style. It is a common point of contention at international battles over which aspect a b-boy should primarily be judged on. However, the Korean dedication to reaching higher levels of prowess in power has in part contributed to the success of many crews, who are subsequently capable of more dynamic performances, simply pulling off moves nobody else can.

Furthermore, Korean breakdance crews are renowned for their strict training regimes, commonly dedicating up to eight hours of practice every day to improve their skills. This forms an interesting parallel with the tough training K-pop idols undertake before making their debut. While the practice of prepping performers for commercial success has been established the world over, from the Motown Era to the Disney Channel, the fact that young hip hop heads in Seoul’s breakdance crews should practice a similar dedication to their art as the trainees at SM Entertainment at first seems unexpected. There is a precedence for the pre-packaged sheen to pop stars, but the hip hop movement is hallmarked by ideas of freedom and independence.

Furthermore, Korean breakdance crews are renowned for their strict training regimes, commonly dedicating up to eight hours of practice every day to improve their skills. This forms an interesting parallel with the tough training K-pop idols undertake before making their debut. While the practice of prepping performers for commercial success has been established the world over, from the Motown Era to the Disney Channel, the fact that young hip hop heads in Seoul’s breakdance crews should practice a similar dedication to their art as the trainees at SM Entertainment at first seems unexpected. There is a precedence for the pre-packaged sheen to pop stars, but the hip hop movement is hallmarked by ideas of freedom and independence.

Yet talented breakdance crews such as the Drifterz are co-opted by the Korean government to become official ambassadors of culture and tourism, in what may be simply a smart way to increase financial gain for both parties, or inherently typical of Korea’s Confucian society, in which office workers cleave to chaebol conglomerates and young starlets to entertainment behemoths such as YG and SM. This means these b-boys have the financial backing to choose to spend the majority of their time training for competitions. One prime example of this government sponsorship would be the creation of R-16 Korea, now known as Respect Culture, a top level breakdance championship and hip hop festival established by the Korean Tourism Organization and the Korean Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, as a means to attract more visitors to Seoul, and so boost the nation’s economy.

Furthermore, the success of Korean breakdance crews has not gone unnoticed. Like many K-pop visuals, Hong 10, alongside fellow members of the Drifterz crew, has appeared in commercials for sports brands such as Nike and Puma. The Drifterz have featured in music videos for K-pop stars including Jay Park, Master Woo and Epik High, in addition to performing at concerts for Big Bang and Psy. In a similar way to K-pop idols spreading Korean soft power through overseas concerts and their legions of international fans, Korean companies have utilised the high energy performance elements of breakdance to market their brands to young audiences.

And breakdance has become increasingly prevalent beyond the hip hop heads, gaining ground in mainstream youth culture via its connection with K-pop. As idol rappers cut their teeth in underground rap crews, many dancers have similarly picked up some breakdance moves as part of their skillset. Going back to the first generation, Seo Taiji and the Boys can be seen showing off their footwork in performances of “Hayeoga” and “Class Idea”. More recently, idols such as Big Bang’s Seungri, Got7’s JB and BamBam, Wanna One’s Daniel, and B.A.P’s Jongup showcase their moves to win variety show dance battles and as part of their choreography in MVs. Take a look at Got7’s “A”, B.A.P’s “Warrior” or even the more the storyline-orientated MV for “Beautiful”, in which Highlight’s Junghyung and Yoseob demonstrate their b-boying talent.

Among these b-boys turned idols, the most prevalent is Jay Park. Since leaving 2PM and forging his own solo career and label AOMG, Jay Park acted as the official ambassador for R-16 from 2011-2013, bridging the worlds of mainstream entertainment and hip hop culture. He also hosted Red Bull BC One when it was held in Seoul in 2013. Jay Park’s role is unique among idols, at an interesting intersection of Korean pop, hip hop and breakdance, as he has established himself as a respected figure in all three worlds and serves to demonstrate the way K-pop and breakdance, despite coming from opposing ends of the entertainment spectrum, can converge to create a new kind of hip hop culture, one which is adopted and accepted by the mainstream, and benefits from this with the financial backing to make it possible for b-boys to continue practicing their art.

The debate over the legitimacy of idol rappers runs deep, as the generic fluffiness of many K-pop groups jars too harshly with the authenticity of hip hop. But while idols such as RM and Bobby must strive to prove their credibility, breakdance has seamlessly slipped into mainstream consciousness, and many Korean b-boys are acknowledged as innovators and masters of the dance while using it to promote everything from Seoul city to Nike sneakers. How has this difference evolved? There is an inherent difference in the opposing forms of these two elements of hip hop culture — where rap originated as a way for MCs to boast of their individual status, while breakdance established itself as a means to keep the peace between gangs and create unity.

The debate over the legitimacy of idol rappers runs deep, as the generic fluffiness of many K-pop groups jars too harshly with the authenticity of hip hop. But while idols such as RM and Bobby must strive to prove their credibility, breakdance has seamlessly slipped into mainstream consciousness, and many Korean b-boys are acknowledged as innovators and masters of the dance while using it to promote everything from Seoul city to Nike sneakers. How has this difference evolved? There is an inherent difference in the opposing forms of these two elements of hip hop culture — where rap originated as a way for MCs to boast of their individual status, while breakdance established itself as a means to keep the peace between gangs and create unity.

One things remains clear, South Korea has made a name for itself in recent years at the forefront of youth culture, the place for cool electronics, must-have beauty products and some of the hottest pop acts on the planet. Meanwhile, leading the professional breakdance scene, Seoul’s b-boys promote the nation’s image and influence in a realm that was once opposed to corporate control and mainstream entertainment. I use the catch-all term ‘breakdance’ for this article in place of more commonly used terms such as b-boying or breaking, yet this is a word originally coined by the media in the 1980s when Flashdance caught the public interest, that subsequently became derided by dancers who felt their identity had been trivialized by pop culture.

In South Korea, breakdance runs parallel to K-pop in many ways; in the dedicated training regimes of performers, the sponsorship deals from advertisers as a primary source of income and the government’s stamp of approval. As K-pop took elements of Western pop music and arguably rehashed them to produce a much slicker model, it has transformed the underground movement of breakdance into an art form that can function independently and as part of pop culture.

In South Korea, breakdance runs parallel to K-pop in many ways; in the dedicated training regimes of performers, the sponsorship deals from advertisers as a primary source of income and the government’s stamp of approval. As K-pop took elements of Western pop music and arguably rehashed them to produce a much slicker model, it has transformed the underground movement of breakdance into an art form that can function independently and as part of pop culture.

The result is global recognition. A mere couple of weeks after BTS showcased elements of breakdance on the AMAs, Vero, a Korean b-boy from the Jinjo crew, won Taipei B-Boy City, cementing his status among the very top dancers in the global breakdance scene. As MYK states on Epik High’s [e]nergy, “Barriers are built for breaking,” and Korea continues to bridge borders, melding elements of Eastern and Western culture to produce some of the best music and dance today.

(hiphoparea, globaldarkness, Drifterz Crew: [1] [2] [3] [4], cantstopwontstop, Red Bull BC One, World Bboy Series, Morning of Owl , Facebook, New York Times, Reuters, Genius Lyrics, YouTube: [1][2][3][4], Images via Big Hit Entertainment, JYP Entertainment, TS Entertainment, AOMG, Red Bull BC One, Floorwars, Hi-Bit Mag, Kidon Bae)