This review contains spoilers.

How far would you go for a second chance at life? For Squid Game‘s despairing contestants, no price is too great — whether it’s risking their lives or taking another’s. In this colourful thriller, 456 contestants compete in childhood games with their lives at stake, all to win the grand prize of 45.6 billion won.

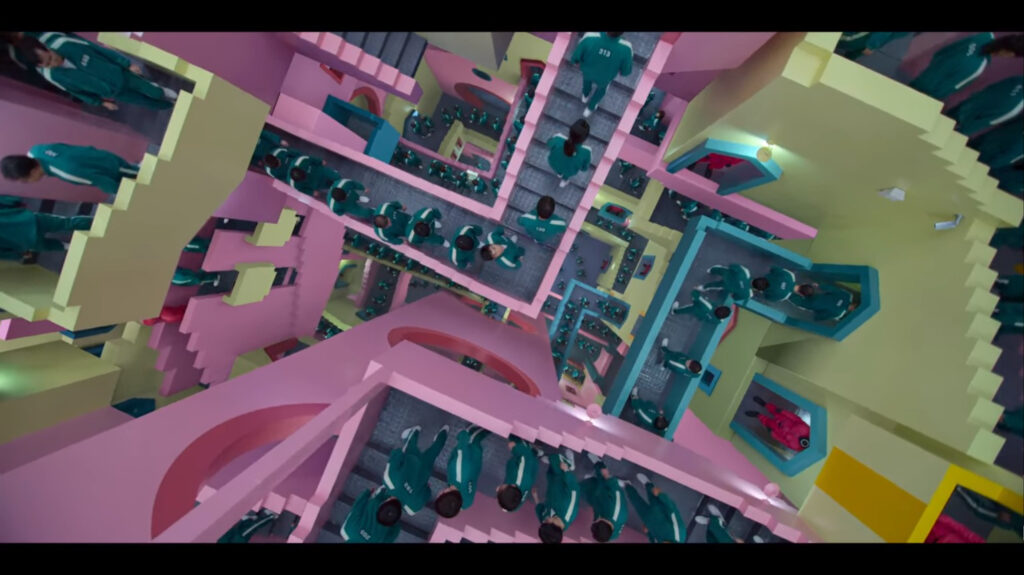

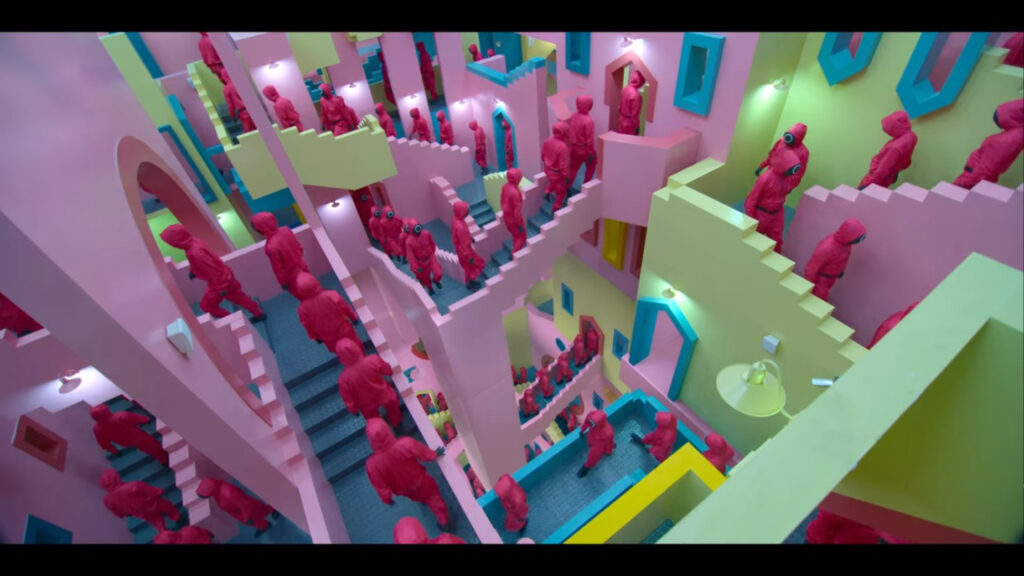

From the get-go, the drama captivates with its ironically cheery visuals, creative set design, and unique choice of characters. Instead of an assemble of righteous heroes, it boldly shines the spotlight on society’s outcasts; many debtors, a gambling addict, an ex-criminal (and SNU graduate criminal), a gangster, a racial minority, and even a North Korean defector.

The first thing we know about our main character, Seong Gi-hoon (Lee Jung-jae), is that he steals and gambles away his elderly mother’s hard-earned cash. Yet despite knowing how pathetic he is, we can’t help but root for him. This is, after all, a man who has hit rock bottom and just can’t get a break; who, against all odds, wins the lottery and against all odds, has it stolen from him. We despise his gambling addiction but admire his desire to give his daughter the best. We would later sympathise with his past when it is revealed that Gi-hoon’s unemployment and divorce stem mainly from a place of trauma: he witnessed the death of a colleague at a workers’ union protest.

Like Gi-hoon, the main cast of characters is fully fleshed out with hopes, dreams, backstories, motivations, weaknesses and character growth. The series expertly paces each character’s backstory across its nine episodes, lending strong emotional beats after every round’s thrilling highs. Furthermore, the backstories are mostly revealed in conversations, creating powerful moments of human-to-human understanding.

Take for example North Korean defector, Kang Sae-byeok (Jung Ho-yeon) and ex-convict, Ji-yeong’s (Lee You-mi) heartfelt conversation in episode 6’s marble game, all while gunshots go off in the background. Their vulnerable exchange not only gives us as viewers insights into their past, but also allows Sae-byeok to form a connection with another person for once. For the first time, Sae-byeok shares her real name with Ji-yeong, a sign of trust that she has withheld throughout the previous episodes (of course, the show just has to twist its emotional dagger further with Ji-yeong’s sacrificial death. Ah, the pain, but also what powerful writing!).

Another key difference between Squid Game and other series of the deadly survivor game genre is its incorporation of choice. Think consent forms, democratic voting and the contestants re-entering the game on their own two feet. However, with choice comes responsibility. The fact that the pot of prize money increases with every player killed only means that anyone who participates is complicit in their deaths. Worse still, sabotage is the norm — contestants use others as a literal shield in the first game, Gi-hoon cheats a dementia-stricken elderly man, and Sang Woo (Park Hae-soo) chillingly slices Sae-byeok’s throat with zero qualms.

At the same time, the drama withholds from overtly condemning the contestants. More than a testament to their selfishness, the game speaks of the extent of their desperation. After all, how desperate does one have to be that playing a deadly game becomes the better alternative?

Equality. Everyone is equal while they play this game. Here, the players get to play a fair game under the same conditions. Those people suffered from inequality and discrimination out in the world, and we’re giving them the last chance to fight fair and win.

As the frontman explains in the quote above, the game offers what the outside world cannot give: a second chance and equality. Yet, by drawing attention to the equality between players, the game masters divert attention from the true inequality between themselves and the players. In a Parasite-like fashion, the lower class fights it out in morbid brutality, while the upper class watches on from a place of comfort, completely unaffected.

The contestants are in no way innocent, but at the same time, they are presented as victims oppressed by the upper class and the system (be it the game’s or society’s). Squid Game holds these two arguments in tandem, never diminishing one for the sake of the other.

In fact, the drama even goes one step further by showing that on the game organisers’ side, the henchmen themselves who instil order and fear are trapped in the system. The parallels between the game’s structure and a company are uncanny, especially when their titles are quite literally “workers,” “soldiers,” and “management”. Like the players, the henchmen’s names are replaced with numbers. Scenes of players and workers marching uniformly remind us that both are simply cogs of a machine, easily replaceable, which is quickly proven true when Hwang Jun-ho (Wi Ha-jun) easily acquires several staff members’ identities by donning their uniforms and masks.

Overall, Squid Game kills it on all levels. Its narrative is suspenseful, plot twists are purposeful and believable, and characters are humanised. Even the workers have personal goals — organ trafficking — which makes complete sense in a game that generates so many corpses. Other than making this fictional world extremely believable, the well-thought-out idiosyncrasies make us sympathise with characters even when they are pushed to hurt others.

It also provides biting social commentary through the range of perspectives it shows, from the contestants, workers, VIPs, and even the most powerful Host. Indubitably, this review has only begun to scratch the surface of social commentary that Squid Game gives. And if you have any insights to add, do comment below! For a drama series nine episodes long, Squid Game certainly delivers tremendous food for thought that lasts far beyond its duration.

(YouTube. Images via Netflix Korea.)