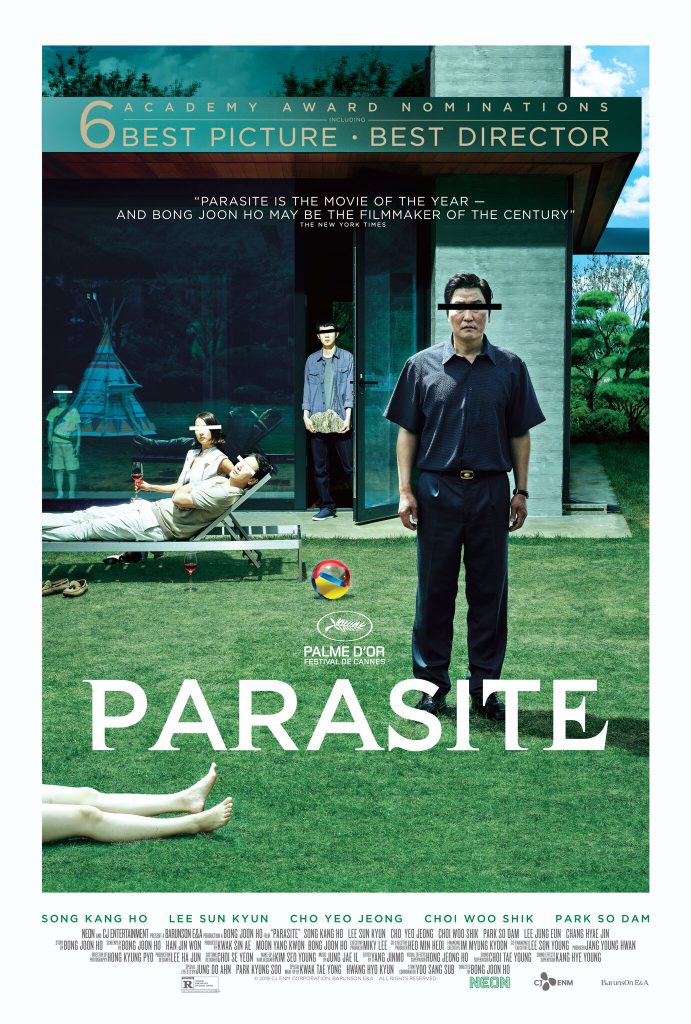

Earlier this month, Parasite made history by becoming not only the first Korean film to win Best International Feature (formerly Best Foreign Film) at the Oscars, but by also becoming the first non-English film in the Academy’s 92-year history to win Best Picture. Celebrated auteur Bong Joon-ho‘s seventh directorial venture also picked up awards for Best Original Screenplay and Best Director, capping off a successful awards season campaign for a much-beloved film.

As a phenomenon, Parasite has done a lot of wonderful, novel and unexpected things; as a film, though, its charm lies in its understated mastery of the art of filmmaking.

This review contains spoilers.

Parasite was originally envisioned as a play, with Bong planning to build the two main houses — the squalid semi-basement where the Kim family survives and the bespoke architectural design where the Park family resides — side-by-side on a single stage. This explains why the film primarily unfolds in these two locations; when the decision was made to transition into film instead, this divide was maintained with other scenes splitting the world into rich (luxury cars, sleek supermarkets) and poor (streetside groceries, school gyms-turned-flood shelters). The two abodes are treated like characters in their own right, carefully constructed to match the script (not unlike how the sets for fellow Best Picture contender 1917 were made):

Characters have to eavesdrop and spy on each other. So in terms of character blocking, all the structure was completed during the scriptwriting stage, and I had to basically force it on the production designer. So he felt a little frustrated, because the things I required aren’t things that actual architects would agree with.

Bong Joon-ho, The Atlantic

So while not necessarily realistic, Bong creates a unique world that deftly juxtaposes the classes. The vertical structure of the film further communicates this divide, with the poor languishing at the feet of the rich. The sets essentially become key characters in Parasite. Cinematographer Hyun Kyung-pyo also details how nature, in the form of light and scenery, is used to mark the land of the rich, while the poor are blocked from natural sunlight and have only weeds for company.

A key symbol of the film is the landscape rock, or scholar’s stone, gifted to the Kim family by their son Ki-woo’s suave friend Min-hyuk (a fitting cameo from Park Seo-joon). The rock is positioned as a harbinger of good fortune and ambition in Ki-woo, while actor Choi Woo-sik also felt it symbolised the pressure his character felt as the eldest son to raise his family up out of poverty. Like the rock, the tutoring offer is also a double-edged sword: Min-hyuk encourages Ki-woo to fudge his credentials, ostensibly because he trusts him to not make any moves on his tutee, a 16-year-old girl. But the reality is that if Ki-woo were to try anything (which he promptly does), he has a better chance of getting rid of him just by exposing their fraudulence.

Though he initially comes across as bumbling and naive, especially next to his savvy, self-possessed little sister Ki-jung (Park So-dam), Ki-woo’s cunning cleanly slices through this facade multiple times: intimidating the pizza shop employee, Byronically charming his tutee and her mother, orchestrating the firing of the original housekeeper (Lee Jung-eun), and smirking at his own gall just before launching the original tutoring con to a whole new level by recommending art tutor “Jessica”. Beneath that sweet exterior is a ruthless ambition to get to the top, seemingly brought forth and spurred on by this landscape rock.

The decisions Bong makes for the characters of Parasite, and the dedication of the SAG Award-winning cast in bringing them to life, allows for a display of greater nuance that blurs the line between hero and villain. Choi Woo-sik’s metaphor of the rock as filial pressure becomes more haunting when it unbelievably floats to the surface as the Kim’s semi-basement floods. On a lighter note, Ki-jung’s aloofness is grounded by moments like her unwittingly consuming expensive dog food. Their mother Chung-sook (Jang Hye-jin) is ruthless but has one of the best, softest, lines in the film in which she regards the rich as wrinkle-free, with no worries about the mundane things that could mean the difference between life and death for a family like the Kims.

Chung-sook’s words are brought to life perfectly in the car following the storm: Yeon-gyo (Jo Yeo-jeong) extols the virtues of the very rain that has left her driver destitute. All she sees are blues skies; the thought that people could be suffering doesn’t even cross her mind. Her only real worry, it seems, is the smell coming from Kim Ki-taek (Song Kang-ho); she plugs her nose while her feet rest on the passenger seat in front, barely a metre away from Ki-taek’s own nostrils. Her feet aren’t smelly or rude because she’s rich: it’s her car and her servant; she can do whatever she wants.

Bong has spoken a lot about the use of smell in Parasite; the Kim family’s shared scent almost gives the game away, but Park family patriarch Dong-ik (Lee Sun-kyun) brings Bong’s thoughts to the fore with his monologue about how Ki-taek’s smell “crosses the line”. As we have seen, the Parks can impose on the Kims all they want, but that is strictly a one-way street.

During the film’s climax, Dong-ik plugs his nose at the smell of interloper-cum-murderer (Park Myung-hoon), the last straw for Ki-taek. While much has been made of this motif, the asides about love and family also merit a mention. Even as he plays Yeon-gyo for a fool, Ki-taek appears displeased at Dong-ik’s dismissal of her. Ki-taek may be a parasite himself, but in his mind, Dong-ik appears to be positioned similarly to his own wife, let alone to society at large, as the film muses.

The most insidious parasitic relationship, though, comprises the epic twist that takes Parasite‘s plot to new levels. The Park family is so well off, and Yeon-gyo so blinded by her ignorance wrought in privilege, that no one except young son Da-song (Jung Hyeon-jun) has noticed a whole human being living in the house’s clandestine underground bunker. Many have highlighted the film’s intention to show us how the poor are left to fight among themselves for scraps, while the rich feed off their desperation.

Parasite has a clear message when it comes to class and wealth inequality — a prevailing theme in Bong’s oeuvre — but it does not always make this message easy to digest. The characters are all presented in shades of grey, justified in one frame and portrayed as hypocritical the next. The film revels in this tussle for money and, more perhaps importantly, control.

Bong’s dedication to visual literacy through thorough storyboarding has been much lauded: Film Exposure-affiliated Twitter account Head Exposure presented the outcome of this beautifully with this thread explaining how the camera shots signal the shifts in control over the conversation, and relationship, in each of the key car scenes. Basically, they who hold the power holds the camera’s gaze:

So in this 1st “car scene”, the Parks’ current driver drives Ki-jeong (Jessica) to the station. Bong opens with a master shot, establishing the geography of the scene. At first, the driver seems to have control of the scene, but the focal point switches to Ki-jeong as soon as… pic.twitter.com/stlpIRrzxM— One Perfect HEADshot (@HeadExposure) January 23, 2020

The film as a whole is beautifully shot without a wasted frame (Bong is famous for not shooting coverage — filming the same scene in multiple angles — and limiting master shots — which set the scene), but one scene that continues to haunt is the very last one. Right after Ki-woo finishes narrating his letter to the visual of him reuniting with Ki-taek in the Parks’ house that he now owns, the sunlight from the ceiling-to-floor windows becomes the few rays that manage to find their way into the semi-basement. The camera gently follows the light down, showing us Ki-woo inside writing the letter, before continuing to pan down.

Bong refers to this as the “surefire kill”, the bullet sent through a person’s head after they have already been gunned down. Its intention is to make absolutely clear that the reunion we just witnessed is never going to actually happen. Just like the landscape rock in the river, Ki-woo’s ambition also sinks as he realises the futility of reaching that higher level of society from his current station. All he has left is the love and pressure that are both not there and too much to bear.

Bong Joon-ho has received much love in Hollywood, from Quentin Tarantino‘s film recommendations to large-scale collaborations resulting in Hollwyood films Snowpiercer and Okja. While his profile has certainly helped, Parasite shows how a captivating story told well can circumvent just about any rule or more that we associate with Hollywood, awards campaigning and cultural hegemony.

Parasite is already being whitewashed; the backlash about subtitles and un-Americanism continues; and the lack of individual recognition for the original cast, both for awards and for literally just knowing their name (the two may be more closely linked than people are willing to admit) still enrages. However, winning Best Picture brought a moment of pure joy and happiness for so many people, something given to us by a film that won over so many with its dedication to perfecting the classic components of cinema. For an award celebrating accomplishment in film, I can’t think of a more perfect honoree.

(The Atlantic, The Hollywood Reporter, Indiewire, NME, Twitter, Vulture[1][2]. Images via: Neon)