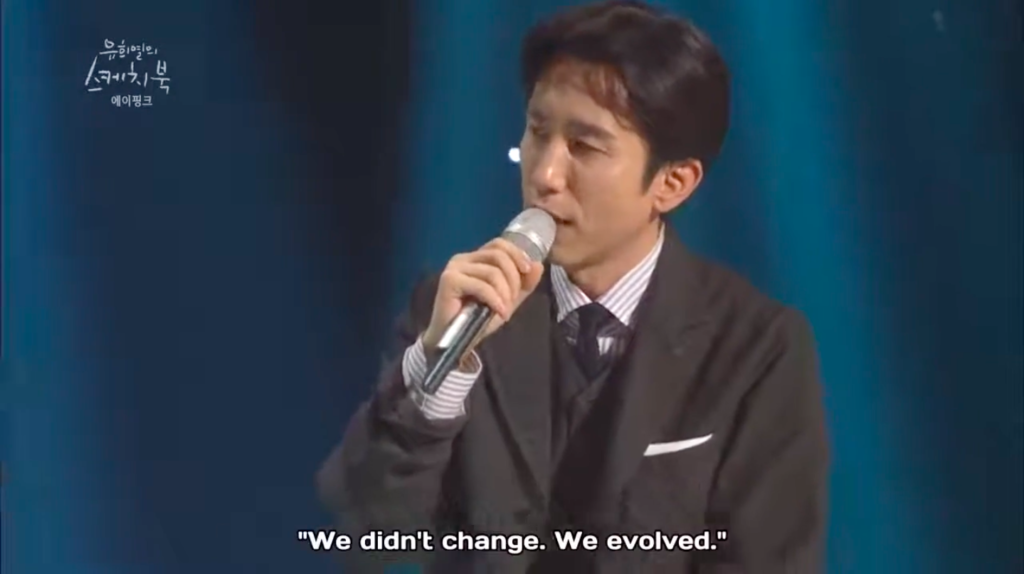

Growth seems to be the umbrella term for K-pop dynamics in the last decade as it moves with an unprecedented speed. In September 2019, I went with Twitter user @mbotorola, one of the admins of Apink Indonesia on Facebook, to the joint concert Super K-pop Festival 2019. His main motivation, of course, was to see Apink, and although I had my reservations due to not keeping up with them post-2016, I kept them to myself. Before the concert, I tried to catch up with the three years I missed, and boy did I miss a lot. The reason? In a 2016 Sketchbook appearance, they told host Yoo Hee-yeol, “[Apink] didn’t change. We evolved.”

Apink debuted in 2011, a time when the K-pop industry was driven mainly by entertainment companies focusing on traditional media. Today, the same industry must humor a disruption of this model that comes from newer companies operating more like IT-based media platforms, matching the expansion of giants like Spotify and TikTok. Where before, idols needed certain skills and networks to navigate national TV shows and radio talk shows, now they appear with more ease on specialized online platforms like Bubble and VLive.

First-generation K-pop group S.E.S’ Bada–whose hairstyle Eunji donned in Reply 1997 and whose stylistic vocal became the blueprint for SM vocalists after her–is now a mother. S.E.S.’s 20-year-old sales records (1997-2000) were recently topped by Black Pink’s The Album (2020). Back in that September 2019 concert, second-generation idols born in the 1980s shared the stage with fourth-generation artists born in the 2000s. Some of these episodes of growth weren’t imaginable to the younger me, who back in 2011 had to contend with watching Apink News in 144-pixel resolution, learn to use HJSplit, and circulate fansubbed ChaoticTM stuff in USB sticks.

Throughout their career, Apink make full use of their strengths. In Eunji, Apink find their sharpest ears, a main vocalist who—along with Super Junior’s Kyuhyun and Red Velvet’s Wendy—belongs to the exclusive K-pop Four Octaves Club, and their public face. Her approach to singing draws from that of idol singers with similar vocal coaching backgrounds, like EXID’s Solji and f(x)’s Luna, who make songs a vehicle to showcase their voice and unique vocal colours. This approach is distinct from that of vocal chameleons like Wendy who mould their voices in service of the song. As a singer, Eunji has a deep understanding of her own tessitura, as seen in how she adjusts the keys for her cover of “Into the Unknown.”

Eunji may be the face of Apink, but the other members play key roles as well. Naeun is still a CF magnet well into her 10th year as an idol, and Hayoung normalized the notion of girl groups having a savage maknae. Bomi‘s vivacious, easygoing personality and skill in working a TV audience have earned her a steady presence on variety shows and in Apink’s many subunits, including BnN, YOS (which started, in a true Bomi fashion, as an April Fool’s prank), and the concert-only Chorong and the Dolai Crew. Then there are the members whose contributions are less visible but still crucial. Chorong, the Captain America to Eunji’s Iron Man, offers support behind the scenes, helping to smooth out the negotiation of their contract renewals and monitoring her members’ solo work. Namjoo pushed for Apink’s reinvention even when Apink themselves were divided on the idea.

At 10, Apink seem to have achieved all the growth milestones not many groups can arrive at: standing tall after losing a member, surviving the seven-year “curse”, passing the test of reinventing themselves, and reaching their second peak. Shinsadong Tiger-produced “LUV”’s record of 17 music show wins remains unbeaten by other girl groups, and they’re the first girl group to hold seven domestic arena concerts in a row. Musically, their recent work for the “I’m So Sick” / “%%” / “Dumhdurum” reinvention trilogy strikes a balance between indie sensibility a la Eunji’s mini albums The Space and Hyehwa on the one end, and Namjoo’s hard-hitting EP Bird on the other unbudging end. The Apink fans whom I spoke to also highlight that Apink’s closeness is family-like, and warms the heart more than the dynamic of coworkers who get along well.

Yet in an industry that has proven repeatedly to be willing to eat its own children, I wondered if Apink’s strengths were enough. More often than not, it is us fans as a collective that gives K-pop groups, especially girl groups, an expiration date. We are often more receptive to defined concepts and take them at face value, as advocation. We want girl power, but only when it comes dressed with leather pants and bling. We campaign for diversity, but at the same time we lean toward musical uniformity by prizing beat-driven and EDM-influenced songs more. The table provided for girl groups by the industry executives is already small, and at times we fans contribute to making it smaller.

Apink’s first attempt at redirecting their musical trajectory wasn’t seen kindly by their own fans, Pink Pandas, who had been too used to Apink’s innocent, girly concept. After the lukewarm reception of the more age-appropriate, mature-sounding “Only One,” their then-label Plan A Entertainment backpedaled and rerouted Apink to the road previously traveled by “NoNoNo,” “Mr. Chu,” and “L.U.V,” never mind the fact that by that time Apink had had equally age-appropriate and mature-sounding B-sides like “Boom Pow Love” and “Kok Kok” or the Japanese tracks “Orion” and “Love Forever”. After “Only One,” it would be another two years before Black Eyed Pilseung worked with Apink again, this time with a much better reception that eventually gained Apink the second wind of their career, “I’m So Sick.”

During the tug of war of whether or not to go in a new musical direction, Apink struggled with a yearlong series of threats from an overseas Chorong fan who felt betrayed by her dating skit in Finding X Pink (2017). To Apink, obsessive fans weren’t new, and they did not shy away from drawing the line to protect themselves. Chorong and Naeun shared on Abnormal Summit that they often had to reject gifts from fans to avoid the risk of bugging devices or hidden cameras. When Eunji put out a strongly worded warning to the bomb threat sender, she too would’ve known what it’s like to obsess over an idol after playing one, Reply 1997’s diehard H.O.T. fangirl Shi-won. Fans often draw the line between a real fan (which can encompass a grey area) and a non-fan to police and gatekeep among themselves, but Eunji’s message, which has since been removed from Instagram, made it clear that there’s only one name for behaviour that endangers lives: a crime.

A decade-long run does not mean there are fewer challenges for Apink, as the Pandas I talked to admitted. While it’s hard to argue that there’s a tendency to equal “international” with “Anglophone-centric” in K-pop in general, it’s also hard to deny the importance of the Japanese and mainland Chinese markets to the industry. Apink lacks the campaign in both. Twitter user @hotjostuff, a fan translator and Panda Fanclub member, said, “If we’re talking global popularity, Apink doesn’t really have a large fanbase outside Korea,” to which @mbotorola agrees. @hotjostuff also added that even during the first and second peak of Apink’s career, there was a lack of international promotion from their label.

This year also saw Chorong go to court to settle underage drinking and teenage bullying allegations, and Naeun leaving Play M Entertainment for YG Entertainment. The allegations involving Chorong pose the biggest challenge to Apink’s clean reputation, even more so than Eunji’s violation of traffic laws by hanging oranges outside a moving car, Chorong’s spelling error during the 2015 Paris bomb attacks, and Bomi’s blackface in an SNL Korea skit. Past experiences with other girl group members in a situation similar to Naeun’s also do not leave me with solid confidence in her continued involvement in Apink’s activities.

Among the more supportive Pandas, there has been a call lately for Apink to pull a Shinhwa and found their own label. The party pooper in me can’t help but ask: Can the girls still access their back catalogue after leaving the label? Can they still use the name “Apink?” (No surprise: Eunji herself admits they can’t.) If Scooter Braun and his Ithaca Holdings could deal such a heavy blow to Taylor Swift, imagine what K-pop executives and labels could do to their idols, who have a much more limited legal backing. “At the core of it, the recording industry is very tight-knit,” says Twitter user @HeroaTin, an anthropologist who studies the workplace in East Asia. “The top brass all know each other, and as a result capitals center around only them. The rest are treated like outsourced contractors.” To illustrate the connections in the upper echelons of the industry, for instance, JYP Entertainment was the training ground for Simon Hong, who founded Cube Entertainment, and Hong later mentored executives like A Cube’s Choi Ji-hoon–Apink’s first boss–RBW Entertainment’s Kim Do-hoon, producer Shinsadong Tiger, and many more.

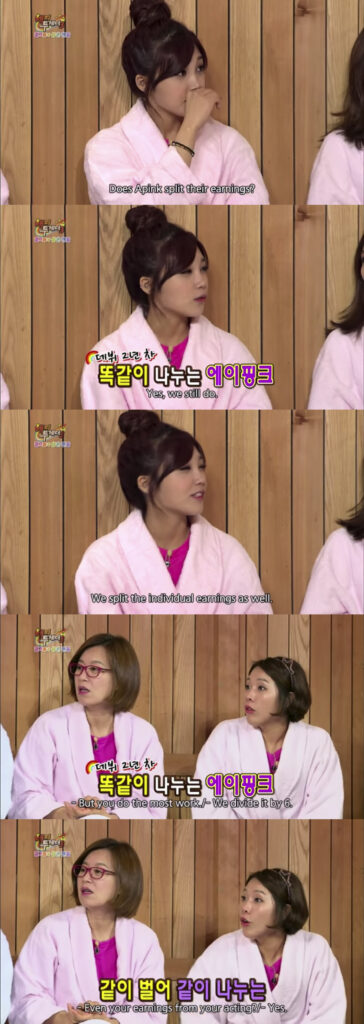

What’s left of the pie then must be shared by the production team, hired brains, and idols themselves. When Eunji chastised Hayoung for being imprudent with her solo debut production expenditure, she explained that it’s because they pay for their own staff. It’s unclear how far self-funding the staff goes, or what types of staff idols have to pay themselves, and whether this only applies to small-to-mid-sized labels, but it is indicative of how questionable wealth distribution, as well as fair pay, can be in K-pop.

Apink also will still need to figure out what they want with their musical direction. The “I’m So Sick” / “%%” / “Dumhdurum” trilogy, while impressive on its own, would have been much more thematically cohesive if put in one album instead of being stretched thin across three underproduced mini albums that leave all their jabs, crosses, hooks, and uppercuts to their title track and call it a day. Whether they should continue working with Black Eyed Pilseung–whose work has been showing a sense of Teddy Park-like fatigued redundancy since 2020–or whether they should involve the members more beyond the annual fan song remains a question.

What remains vividly, at the end of the day, is Apink’s legacy as a well-traversed girl group. In an industry like K-pop, where so much keeps evolving and refusing to be fossilized, Apink is exemplary in striking a balance between managing each member’s aspirations and the group’s focus, between building a healthy relationship with fans and calling them out for offenses, and most importantly, between what has shaped K-pop and what still needs to change in K-pop.

Theresia Pratiwi is a linguist and educator, and she can be reached on Twitter (@thranduilion). She thanks Twitter users @hotjostuff, @mbotorola, and @HeroaTin for their help with this article and wishes all Pandas happy belated 10th anniversary.

(YouTube. Images via Play M Entertainment, KBS, 1theK)