In the world of K-pop, different countries and cultures find their place in the landscape in different ways. When it comes to Western nations, these positions are pretty clear, and pretty dominated by the world’s biggest cultural force, America.

But what about Britain? Where does my homeland—my soggy little island—fit in? As much as Britain doesn’t have the (relative) proximity to Korea that Australia and New Zealand enjoy, or the sheer heft of America’s power, it has always had its own form of influence, Shakespeare and all that. In the sphere of Korean pop music, has it been influential?

You would think not, until you start to think about fashion. Whilst Britain may not produce idols, or a music style that has hit it big in Korea (alas, no faux-cockney indie pop for K-pop), there is a multitude of aesthetics that can be traced back to it.

British style has influenced some major cornerstones of fashion for hundreds of years. As rather an old nation, with a slight (i.e. absolutely huge) obsession with class, the country has a rich history of aristocratic clothing choices. In the 20th century, this history got a rude awakening as society changed along with class fortunes. Thus, Britain started to see some of the most exciting fashion movements, away from the classic and traditional and towards the anarchic and rebellious. If I had to sum up British fashion, the key terms would be: tradition and subversion.

So what has that got to do with K-pop? Bearing the above in mind, a lot of British fashion has influenced K-pop fabric choices, outfits, brands and even MVs. As common cyphers for the classic mixed with the modern and revolutionary, they add unique dimensions to K-pop aesthetics. Does this aesthetic show K-pop breaking rules, or conforming to them? Understanding the British aesthetic itself will give us a clearer idea.

Whilst British fashion is complex with a long history, there are certain styles and eras that became famous enough for a place in the global imagination. From the grandeur of the Tudors to the stuffiness of the Victorians, upper classes have long had distinct looks that illustrate their wealth and separation from society. But the most transformative period for the UK came later, in the 20th century.

Perhaps the most visually iconic decade for Britain, as for a lot of the world, was the 1960s. This was specifically because this was the moment that society truly started to break away from traditions, with London as an epicentre of the new, emerging culture. Key to this aesthetic were: bright colours; geometric shapes; graphic makeup and prints; long boots or socks, and of course, the miniskirt.

Made famous by London designer Mary Quant, this skirt was a clear visual breakaway from the conservative skirt lengths of women in years gone by, and a shorthand for the decade’s sexual freedom. Women were showing their legs for the first time, and it was a statement.

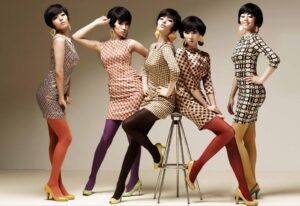

Many of these 60s aesthetics have made their mark on K-pop over the years. From bold-coloured, double-breasted mod-style suits worn by the likes of Shinee, to the block coloured tights and printed minidresses of Wonder Girls, the boldness of the fashion is distinctive and sharp whenever used. But it’s that invention of Mary’s, the miniskirt, that has the biggest role in K-pop fashion.

It would be futile to list every girl group who’s ever worn them, because it’s part of the female K-pop uniform at this point. Even if they wouldn’t nod as directly to the decade like Twice’s “Eyes Wide Open” album shoot, every girl group worth their salt will appear in a hemline significantly north of the knee.

A symbol of defiance against older generations in the 60s, the miniskirt in K-pop occupies a similar tradition today. A far cry from traditional full hanbok skirts, the miniskirt in K-pop is a direct opposition to the fashion that has come before in Korea. Short may not be as shocking today for some people—though it probably still is for many elder Koreans—but it still acts as a shorthand for the distinctly modern in K-pop outfits. For instance, when Black Pink wanted to modernise their hanboks for “How You Like That”, it was done by dramatically shortening them. This idea flourished first and foremost in 1960s London, and has become almost ubiquitous in K-pop today.

Another extremely common element of K-pop clothing that owes its origins to Britain is our most iconic fabric: tartan. Originating from the Highlands of Scotland and Ireland, this fabric is perhaps the clearest symbol of Britain’s fashion changing from the high-status to the anarchic.

The distinctive lined prints in varying bold colours were initially the preserve of the aristocracy and royalty; the Royal Family even have their own distinct tartan print, which you need royal permission to wear. Because of these lofty associations, tartan became the perfect fabric to be appropriated by the punks of the 1970s. A far cry from a Scottish nobleman, these punks took tartan and paired it with ripped clothing, leather, fetish gear and safety pins. Permission from the Queen? To hell with that, they’ll do what they like. Tartan and associated plaids became a symbol of rebellion in fashion.

How does this speak to the fabric’s use in K-pop? Again, like the miniskirt, tartan has made a firm home in K-pop outfits over the years. From the traditional distinctive red, black and green through to perhaps its most famous iteration in Burberry check, idols are never far away from a tartan moment.

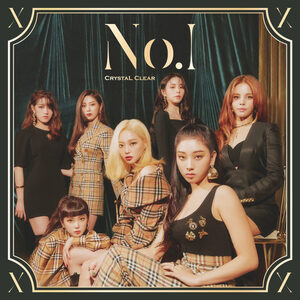

F(x) in “Rum Pum Pum”, Red Velvet in “Ice Cream Cake” (and Wendy in “Peek-A-Boo”), Sunmi in Dazed Korea, V in BTS’ “DNA”, CLC in their cover for No. 1: the list goes on. However, pairing the print with a simple notion of ‘the rebel’ doesn’t really hit the mark here. It wouldn’t be too simplistic to read this common fabric choice as one that is simply visually striking, because, as a print design, it is striking. The MV thumbnail for “Rum Pum Pum” is all the more vibrant because of the tartan pattern, and Wendy’s dress in “Peek-A-Boo” adds a texture to the rest of the group’s block colours, for example.

But this usage doesn’t have quite the same intention as in the 70s. The fabric’s use in K-pop has reached an interestingly detached point from both its aristocratic origins and its use in punk. In appreciating the fabric simply for its vibrancy and distinctiveness, K-pop fashion has forged beyond the polarised point tartan was at in Britain. The print is not a marker of class at all in this world, which, in itself, is a strong statement of the power K-pop aesthetics have to subvert existing ideas from cultures as different as this one.

Aside from the clothing and styles that the UK popularised, Britain has also created some of the world’s most famous designers, and the K-pop world has noticed. As mentioned above, Burberry is a brand that seems to hold a particular interest—NCT‘s and SuperM’s Lucas is even a Global Brand Ambassador. Stella McCartney‘s outfits and John Galliano’s work have also peeped onto the scene, and experimental designer Gareth Pugh even dressed 2NE1 for part of their “I Am The Best” video. But a conversation about British aesthetics can’t be had without mentioning perhaps the two most famous combiners of the punk and the traditional: Vivienne Westwood and Alexander McQueen.

These two designers are both iconic for shocking and revolutionising the fashion industry through truly bold design choices that no one else often dared. Vivienne connects directly to the punk movement, being one of the key designers of the actual clothes worn by actual punks in the period. Both are known for strong references to British history (including tartan), beautiful shapes, modern interpretations of those tastes, and elaborate drama. Whilst their clothes may not be quite as easy to spot in the K-pop scene as Chanel or Gucci, when they are present, they make a statement.

Black Pink are particularly strong examples of this. In “Kill This Love” , Rosé wears a yellow floor-length layered-ruffle McQueen gown that emphasises the drama of the song’s pre-chorus, while Lisa’s peplum biker jacket screams ‘bad-ass rapper’ perfectly.

Jisoo gets a similar dramatic moment through the red gothic lace McQueen she wears in “How You Like That”, whilst Rosé and Lisa highlight the ‘anarchic girl crush’ mode of “Lovesick Girls” with bright, tartan-esque two-pieces from Westwood. The choice to use these particular British enfant terribles sits well with Blackpink’s ‘fashionistas with a bite’ image. Who better to understand the demand that this image has for both classic feminine pieces and a modern, in-your-face visual, than British designers with the history they have to work from?

In the work of Westwood, McQueen and beyond, an encapsulation of Britain’s polarised visual aesthetics comes together beautifully. It is this opposition of rebellion and tradition, aristocracy and anarchy that symbolises the key moments of Britain’s fashion story, and it is these moments that K-pop has taken and used for its own expression.

From the miniskirt as a coda for personal freedom, through to the subversion of tartan as a vibrant pattern for everyone (not just the Queen), K-pop fashion has run with these key ideas that Britain has given the world.

Of course, Britain is not the only country whose society is polarised: Korea has similar struggles with differences between generations, genders and more. In borrowing from our fashions that most strongly play with notions of conservatism and progression, K-pop fashion is able to play with these ideas itself. From one old nation whose cultural shift influenced the world, to another whose culture is doing the same right now—the British fashion aesthetic in K-pop is the creativity of this shift, and the possibilities in the oppositions they present.

(YouTube. Korea Herald. Images via: SM Entertainment, HYBE Labels, JYP Entertainment, Cube Entertainment, and YG Entertainment.)