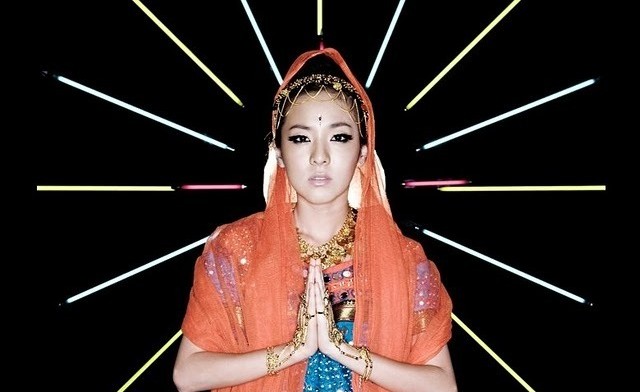

Queendom is the latest in a string of idol-based survival show from Mnet, pitting debuted girl groups and female idols for our entertainment. Cube Entertainment‘s (G)I-dle is competing, but have become a talking point for what many believe to be all the wrong reasons. From the “ethnic hip” concept to the imitation of racist whooping, there is definitely a lot to unpack. One detail that has captured the attention of many was the bindi Soyeon wore for the group’s performance of 2NE1’s “Fire.”

This isn’t the first time bindis have appeared, or appeared to be an issue, in K-pop. The community response from South Asians all around the world often varies. To help capture this variation, Gaya is joined by some of the participants from our Roundtable on the thoughts and experiences of South Asian K-pop fans: Zea, Rimi, Aastha and Anthea Isaac of Destination Kpop, The Kraze and Let’s K-pop India.

Gaya: To begin with, I think it would be a good idea to understand each person’s context and their relationship with bindis/pottus/whatever you call them.

Rimi: It goes without saying that the bindi carries much cultural meaning in India, especially given its location. The spot on the forehead between the eyes is considered to be the sixth chakra, or third eye, and the third eye represents enlightenment. It is often seen on images of the Gods, particularly Shiva, who is “The Destroyer” in the Hindu trinity.

Thus, my answer may surprise you: I do not give it much significance. For me, it is an accessory, a beauty item to be used as and when one desires. It may represent the third eye, but it is not the actual third eye itself, and ought not to be confused with the real thing.

Gaya: I consider bindis part of the “uniform.” If I’m wearing “Indian” clothes, I’m wearing a bindi. I actually have stashes of maroon, drop-shaped bindis in my wallet, car, dance outfit bag, so that I’m never caught out. Sometimes I don’t wear one in dance class and I end up feeling a little guilty, especially when even the non-Hindu girls are wearing them. Of course, I don’t think it’s necessary that non-Hindus wear bindis and it’s a bit sexist when you notice that boys don’t have to wear shit, but I still feel compelled to wear a bindi when I’m in my ethnic gear, as a Hindu woman.

I used to wear bindis to primary school and would be bullied for it (among other things) until one day my mother sadly said that I should stop wearing it to school. So I stopped until grade six, at which point I realised that I could wear bindis, that those bullying me for it were the ones in the wrong, It was such a liberating feeling, and wearing a bindi with my school uniform again felt like an act of defiance. Things went along smoothly until I was involved in a non-violent, but still scary, altercation on public transport, at which point Amma angrily insisted I stop.

Aastha: I grew up distancing myself from any physical items that outwardly pointed me out as an Indian, just so I could assimilate and blend in. I would westernise my Indian wear as much as I could: jeans with kurtis to the temple, no bindis, no bangles, no kajal. There were instances I would wear some bangles, since they pass off as bracelets, but I stayed far from bindis. My childhood stigmatisation of “Indian-ness” is embarrassing, but it was a product of my society. It was so much easier (and cooler) to be part of the norm. It’s kind of ironic, because I’m so obviously Indian from my skin-colour, but I truly believed that if I tried hard enough I could get rid of my Indian-ness; thus, getting rid of the bindi was a terrible, but significant, part of my growing up experience.

But I still saw many non-Indian friends wear bindis for aesthetics, and I think that’s where the issue lied. Society claimed that bindis were okay if they looked pretty, but if they started becoming more than that, then they were too much. If bindis established you were different, and that you had a part of you others were not willing to understand, you automatically became ostracised. Any Indian who wore a bindi would obviously be identified as other, and this internalised perception made me create a whole other non-Indian persona, which I’ve only recently started to shed.

I’ve stopped shying away from putting on a bindi, and I don’t think it’s embarrassing to wear my salwar-kameez out casually. It’s still a difficult process of unlearning, though, and sometimes I do get frustrated at myself for having been such a malleable child.

Anthea: I am a non-Hindu residing in Tamil Nadu but that doesn’t stop me from understanding the importance of bindis in others’ lives. I still remember playing games by wearing a self-made pottu with powder and chalk dust. My parents have always been strictly against such games but I was not sure why until I grew up. I soon learnt how important it is to people: it defines religion, rituals and even identity. Of course, we have different types of bindi to wear at different times.

In school, I was always asked to wear a bindi while performing a group dance. It never really bothered me much, as it has nothing to do with my inner self. At times as a child, I badly wanted my religion to have a practice of wearing bindis, since I found it pretty. My friends have different ideas as well: some become upset if they lose their bindi, their parents shout at the top of their lungs to make them wear one, while some just never bother. We can neither blame nor mock them, it is the tradition and auspicious rituals they prefer.

Sometimes, I feel that most people forget the difference between co-existing and ignorance. Many tend to be ignorant while calling themselves liberated. It is true that we must learn to adapt and appreciate any culture but we can’t just practice other’s holy rituals. When a particular person or community is not happy with an intervention, then we must step back.

For instance, many including me might have been comfortable with me wearing a bindi for a dance but I can’t be sure if my grandparents and relatives or my friends’ family would be ready to accept that. Every coin has two sides.

Zea: As a Pakistani-born Muslim woman, bindis didn’t necessarily always hold a lot of religious or cultural value for me simply because, well, I didn’t wear bindis and nobody I knew did. Henna, on the other hand, as well as bangles, did hold immense significance for me as did the shalwar kameez, which was what I lived in — and still do, just inside the house, not outside.

It was when I immigrated to Canada at age 11 that I realized white people don’t care much for the subtle nuances in South Asian cultures and religions and as long as you had darker skin, reeked of tarka, and brought highly fragrant food for lunch, you were lumped in the Brown subcategory in their mind. I remember wearing kurtis with jeans to school and feeling isolated and judged until I begged my mom to buy me tops for the next school year. I remember the principal of my elementary school calling me into her office and asking about my showering schedule (because I smelled like Brownness). I definitely remember using the ‘Black and White’ filters to make myself look whiter.

I rejected so much of my Brownness to fit in that when I see the very people who all but forced me to do it raving over the taste of “curry”, praising the beauty and intricacy of henna, and even incorrectly using yoga terms to seem cultured, it angers me. It angers me that they can embrace the beautiful parts of my culture and receive praise for being “cultured” and “open-minded,” but when I do it I am “backwards” and should “go back to my own country if I can’t assimilate.”

Gaya: Just reading these different experiences has shown me how we each have our own experiences with bindis and are far from a monolith. It goes some way to explain the varied responses that come forth when the issue of bindis and cultural sensitivity come to the fore.

What was your reaction when you saw Soyeon wearing that bindi?

Rimi: I think it’s clear that when I first saw the performance, I didn’t think anything of Soyeon’s bindi, and was surprised by the raging Twitter discussion on it. With a Korean idol wearing it for the purpose of that performance, I didn’t really think of it as a bindi per se, but more as a shiny thing on her forehead to accessorize the outfit. Looking again, however, it clearly is a bindi. It makes me wonder if Soyeon herself even realized she was wearing a bindi.

Aastha: My immediate response was an eye-roll and a mutter of “not again”.

I wasn’t angry; I was too tired of Indian accessories and themes being used aesthetically time and time again and repeated anger just felt futile. I was annoyed, though, because yet again the “pretty aspects” of my culture were being used to enhance their image, and they would get no flack for it. Had there been a reference to India, or perhaps there had been Bollywood-like beats being used, I could have closed one eye. But the fact that the attire was conscientiously paired with ululating just so it could all fall under “ethnic hip” shows a huge lack of awareness of the significance of the symbols they choose to use.

You could say that this is just K-pop, and the music is far removed for South Asian culture, but if the research can be done to understand African music, and to incorporate Indian motifs and mantras (Norazo‘s “Curry”, Lee Hyori’s “White Snake”), then why can’t it be done a step further to understand what these things mean?

Gaya: I think with both that conversation (G)I-dle had regarding their concept for the performance (“ethnic hip”) and the fact that the original “Fire” MV also featured Dara in a bindi, wearing a bindi was a deliberate choice. The whole point of the performance was to take on an “exotic” air, hence the uncomfortable mix of many influences. Also, the “whooping” gesture to emulate ululating is downright racist.

Whenever I see a bindi on a non-brown person, the Kill Bill siren starts to go off, everything takes on a red tinge, and in my mind’s eye I can see Gwen Stefani placing stick-on earrings on her forehead while wrapping a sari around her waist to wear as a sarong on a ’90s red carpet.

I don’t know if it’s worse when it’s just worn apropos of nothing with no relevance, or it is part of a wider “Indian” theme, because that never really works out well, either. Selena Gomez‘s “Come and Get It” was messy, and we all saw what WM Entertainment and Oh My Girl did with “Windy Day”. There is no actual need to wear a bindi, so why do it? Having the act of wearing a bindi become so stigmatised for me growing up, it’s very difficult for me to see it as just putting on another accessory.

Rimi: While I didn’t immediately think of much of Soyeon’s use of a bindi, Lee Hyori’s “White Snake” is a whole other thing. The incorporation of Indian motifs and chants, sexualizing the Gayatri Mantra, was indeed racist. Clearly no research was done into its meaning, or they just did not care. It forever stands in my mind as a mark against Lee Hyori, and I cannot be bothered to check out her more recent work. In the same way, I take offence with G(I)-dle emulating ululating.

The difference, in my mind, is that I don’t attach any significance to the bindi. But when I see Soyeon’s use of it in the context of your experiences and understanding the concept of the performance as “ethnic hip”, then it is no longer something removed from the Indian context and my initial disregard starts to crumble.

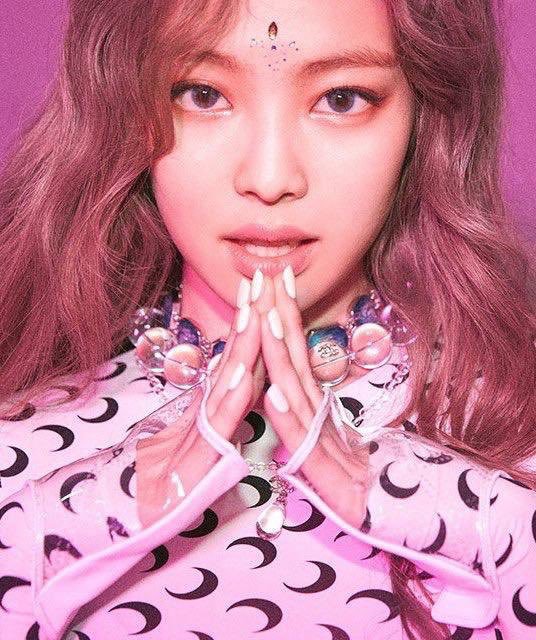

Zea: I think that is why (G)I-dle appropriating the bindi, as well as henna in “Latata”, and Black Pink‘s Jennie and Dara appropriating it before them, angered me enough to vent my emotions on Twitter; these idols are using aspects of brown culture to seem cultured and cool but unlike me, they can just take these accessories off while I cannot dissociate from my Brownness when it is uncool and embrace it when it becomes cool again.

I think my diasporic experiences definitely colour my emotions because South Asians living in South Asia don’t face the subtle xenophobia and racism that diaspora members do; this is why you’ll see comments like “I’m Indian/South Asian and I see nothing wrong with this,” and while I respect their opinion, they have not had the same lived-in experiences we do and cannot realize how deeply it cuts to see someone accessorizing the very aspects you were demonized for.

Anthea: I was not offended at all. It might be because I come from a non-Hindu family. As mentioned, I have worn bindis for various performances and stages. No one ever accused me because they knew I never meant it in an offensive way. As for idols, I am also sure that they won’t really know the actual seriousness of bindis and the customs. They wear it as a part of their costume but I think people take it way more seriously. It is not just Indian customs, we can also see many props of various religion used for aesthetic and fashion purpose but we hardly notice.

Gaya: How can we respect our own experiences and thoughts on bindis, while reconciling that with K-pop’s use of bindis? Is it always OK because the bindi is considered an accessory? Is it never OK because it is worn out of context? Or is it something we consider on a case-by-case basis?

Anthea: I will go with the case-by-case concept cause that is what it ultimately is. The ignorance can be accused but aren’t we all ignorant in one thing or another? I wouldn’t really call this ignorance; it’s just they are not aware of what we Indians do and believe. for example, we often have Korean exchange students in our college. They probably step in without any knowledge on what to wear, how to behave and so on. We along with our staff teach them the importance of certain traits and then let them explore for themselves. And, that’s exactly how it works everywhere. These points don’t mean that I want everyone to neglect the case but to look at in a broader way as they are just learning to socialize and move friendly with us as much as possible.

Gaya: I don’t view bindis as purely aesthetic, but it’s not a universal view. I would draw a distinction in that being in a majority-Hindu environment would make wearing bindis more a case of assimilation than it would be for Soyeon wearing a bindi during a performance in South Korea.

Aastha: I used to have a knee-jerk reaction: it was never okay to wear accessories out of context. I’ve come to loosen my stance over the past few months. An idol’s (or anyone’s, really) usage of bindis and other accessories should be analysed contextually, and therefore considered case-by-case. For example, Hyerim’s maang tikka-inspired jewellery for “Me & You” was iffy for many, but considering that they were all supposed to be brides I was okay with letting it go. But I’m also aware that not everyone feels the same.

(YouTube[1][2]. Images via: Mnet, Wild Thing, Sunsilk India, YG Entertainment. Shiva image: credit to owner)