The sex trade always seems to find its way into discussions on the Korean entertainment industry. Sponsorships — the act of having a sponsor who will help boost your career and and support your lifestyle in return for sexual acts — is certainly a big issue, but this site’s coverage of the sex trade has almost always focused on the entertainment industry, on the cases from idols and actresses, from the suicide of Jang Ja-yeon, to Se7en being caught red-handed going into a massage parlor when he should have been in his military camp. While these articles concentrated on these instances act as a starting point in the discussion, it should not be overlooked that these instances are just a drop in the bucket when compared to what is happening on the macro level. Sex work — be it voluntary or not — is present society-wide, and limiting the discussion to just the entertainment level does it no justice.

The sex trade always seems to find its way into discussions on the Korean entertainment industry. Sponsorships — the act of having a sponsor who will help boost your career and and support your lifestyle in return for sexual acts — is certainly a big issue, but this site’s coverage of the sex trade has almost always focused on the entertainment industry, on the cases from idols and actresses, from the suicide of Jang Ja-yeon, to Se7en being caught red-handed going into a massage parlor when he should have been in his military camp. While these articles concentrated on these instances act as a starting point in the discussion, it should not be overlooked that these instances are just a drop in the bucket when compared to what is happening on the macro level. Sex work — be it voluntary or not — is present society-wide, and limiting the discussion to just the entertainment level does it no justice.

This brings us to the documentary, Save My Seoul. This isn’t the first time I’ve ever heard of the documentary. When I was researching for my article on sponsorships and prostitution, I had heard of the project losing their investors and starting a Kickstarter for funding. Now, a year later, the documentary has premiered at the 33rd Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film festival, and it has won the Grand Jury Prize for Best Documentary. It is now available to rent and buy on iTunes, as well as on YouTube, Google Play, and Vudu.

Korean-Americans Jason Lee and Eddie Lee are the brothers behind the documentary. On the iTunes store page, the documentary is described as aiming to look at prostitution in Korea, stating that “this problem is rooted in issues far deeper than exploited girls and lustful men. Instead, it’s a consequence of a culture and government that condones and turns a blind eye to the biggest human injustices of our time.”

That is a heavy statement.

The documentary is anchored by the Lee brothers, whose visit to Korea is spent uncovering what they can about the Korean sex trade industry. This was sparked from a previous short film created by Jason Lee, the director and the founder of Jubilee Project. This short film, entitled “Back to Innocence” (featuring a young Megan Lee) depicts a situation wherein the young female is dragged into bed by a visibly older male. This was set as a work of fiction, but this also happens to be something that happens around the world, and to some women, is a daily occurrence. This is brought to their attention by a Korean pastor, and the notion to create a documentary focusing on prostitution and sex trafficking in South Korea began.

When South Korea is talked about in mainstream media, it is almost always in a positive and benevolent light. Their economy has risen to new heights within just one generation, the country has one of the best economies in Asia. K-pop is a soft power to be reckoned with, and K-dramas have only helped with that popularity.

Not talked about in the mainstream are the problems that South Korea faces, one of which are laws that are restrictive or do not allow proper justice to be served, especially if you are female. This problem goes further and is rooted far deeper than expected. According to Eddie Byun, a Senior Pastor who is an advocate in the fight against modern day slavery, the reason why this problem is not addressed, and in fact, is ignored, is because “we [Koreans] are very good at saving face and putting on the proper image of what looks good on the outside.”

This is also seen with the street interviews. When asked about the instance of prostitution, all the interviewees dodge the question, with one female even saying that the question is not appropriate. The sentiment is also reflected in the interview with Dr. Na-young Lee, a Professor of Sociology from Chung-Ang University. She speaks about the hypocrisy that is prevalent in Korean society — one which acts “so proper and ethical as if they don’t know or care about sex. But in private or certain places at night, they become totally different people.”

This is also seen with the street interviews. When asked about the instance of prostitution, all the interviewees dodge the question, with one female even saying that the question is not appropriate. The sentiment is also reflected in the interview with Dr. Na-young Lee, a Professor of Sociology from Chung-Ang University. She speaks about the hypocrisy that is prevalent in Korean society — one which acts “so proper and ethical as if they don’t know or care about sex. But in private or certain places at night, they become totally different people.”

This segues into another set of interviews, primarily men, who explain that prostitution is inevitable, it happens everywhere, and a necessary evil. In a later set of street interviews, these same men are also strong in their belief that prostitutes go in willingly every single time, and that they actually seduce the men and “that’s why men sexually harass them.”

What this documentary does so well is illustrate the problem by providing human faces — albeit blurred (and rightfully so), but still humanizes them in a way that normal recitation of facts and figures or interviews with experts cannot do. It strikes a balance between the data, which seek to give further emphasis to the issues the female victims are talking about, and weave the street interviews and expert interviews at an even pace. This is due to the excellent editing by their editor and producer, Jean Rheem.

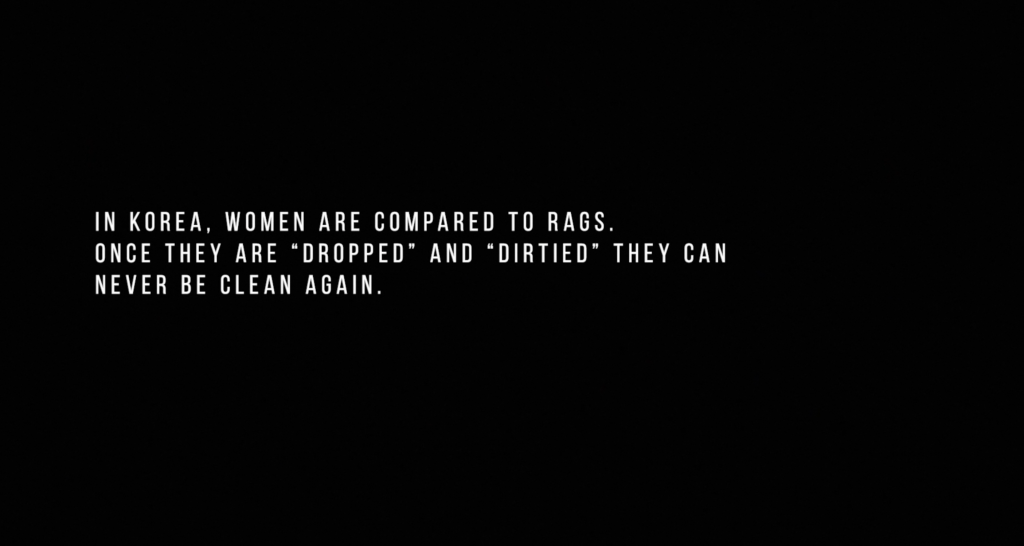

The main focus, and rightfully so, are the stories shared by the women. This humanization is often missing from the previous short documentaries about the sex industry in South Korea, mostly due to the difficulty in persuading women to come out with their story. Due to the stigma against prostitution, the women do not want to show their faces because revealing their face would not be seen as courage, but rather, as recklessness. This stems back to how Korean society is said to see women as rags, not as humans, but rags. Once a woman “is used,” they can never be “clean” again.

From the stories told by the women, there is a common theme noticed. It would be easy to proclaim that this is an instance of editing magic, but it is woven together with expert interviews who concentrate on these topics. The main theme is that these women ran away from difficult homes where they had lived with either an alcoholic parent, a parent who beat them or raped them, or a combination of both. There is one who was raped by a friend of her older brother, reflecting the worldwide data wherein 1 in 5 girls aged 15 to 19 experience violent or sexual abuse by someone they know.

In Korea, there are over 200,000 runaways from home every year. They are amongst the most vulnerable. Of the 200,000 runaways every year, the Seoul Metropolitan Government estimates that over 50% are taken in and become involved in the sex trade. Once they are taken in, they are given some money to “help” them get on their feet, and before these women know it, they become prostitutes. As Wol-Goo Kang, the Director of the Women’s Human Rights Commission of Korea, puts it: “Once they’re out [of their homes], they are surrounded by people waiting to prey on them.”

This wouldn’t be a problem if they did so willingly, and were able to leave easily. However, once they begin, they are again given money for their use. This piles up until they are in debt, and are unable to leave. The average debt that prostitutes usually have is anywhere from $21,000 to $32,000.

In the documentary, this is told by the experts while cutting to interviews with the victims. It, again, grounds these lofty facts and figures with very human stories. Once they are pushed into sexual service, sometimes unwillingly, it is difficult to get out. Even when they run away, and run far, far, far away, they are somehow followed and physically dragged back.

Going in, one of the questions I had was wondering if the documentary would address the differences between prostitution and sex trafficking — and it does, in a way. But it seems like the documentary instead focuses on the instance wherein voluntary prostitution, a form where the person can willingly leave sexual services, crosses with forced sexual labor, where the voluntary crosses the lines and becomes sex trafficking.

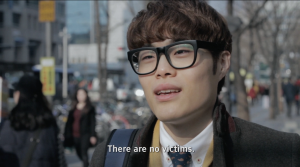

This brings us to the second portion of the statement to describe the documentary: the government condones the practice and turns a blind eye. The way in which the documentary illustrates this is through the experience of the brothers going to the police station to ask about prostitution; is it illegal and is it okay? The first station they go to avoids answering, telling them to go to the capital office for the Women and Adolescents Department. Upon arriving at this office, they are then told that the people of the department are unavailable as they are at an event. From there, they are pointed to another police station that also have a department. There, they are told to go to the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, emphasizing that the police are only there to crack down — but only if there are victims.

To this police person, he says he doesn’t see them as victims, even though the laws proclaim the prostitutes as such. This reflects the overall view of men interviewed — prostitutes are seducers, they deserve what sexual abuse they receive, and that they are worthless due to being “used.” Going to a prostitute is seen as being a rite of passage — a man becoming an adult — and as part of the “hosting culture” of the Koreans.

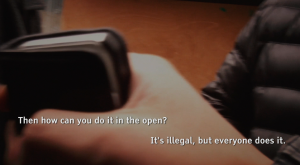

After being told that they have to go to the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, the brothers switch their tactic. Instead, they go to a police station just a short distance from the “588” red light district. There, they ask if it’s okay to go to a brothel. They are told “we don’t really go out of our way to regulate anymore,” adding that they only go in when there is a report. The visit is ended by the policeman telling the Lee brothers that prostitution is illegal and to “go have a good experience.” This illustrates that the police look the other way. The prostitutes interviewed also echo this sentiment, saying that the pimps and the police have a very close relationship.

If there is one criticism that I have, it is only several people were asked, which is not an indicator that the government actively turns a blind eye. There would need to be more visits done, in various districts, to indicate that there is even a trend of the police turning a blind eye. That being said, it is a starting point, and one that can be followed up upon for a bigger analysis.

If there is one criticism that I have, it is only several people were asked, which is not an indicator that the government actively turns a blind eye. There would need to be more visits done, in various districts, to indicate that there is even a trend of the police turning a blind eye. That being said, it is a starting point, and one that can be followed up upon for a bigger analysis.

Moreover, going to the red light district for sexual services is seen as part of company life; and it is estimated that Korean firms’ usage of the corporate credit card for sexual services amounted to $1 billion in 2013. As Dr. Na-young Lee puts it: “For the sake of the nation’s economic growth and safety, the government systematically exploited woman’s body.” This stems all the way back to the post-Japanese occupation, where the government set up “special districts” for the use of American troops. These “special districts” were composed of dance halls and brothels, and kept the then destitute Korean economy afloat, making up of at least 25% of the GNP.

The final portion of the documentary has the Lee brothers go to Miari armed with a pen camera. They visit at least 15 brothels. In a brief montage of these brothels, a common image was that upon entering and being presented the girls, they were, at least 80% of the time, sitting on the floor in a room that was lit low with a purple lighting, wearing white shirts or bride gown-like dresses. It was a short montage, but it is one that is memorable.

The documentary is only one hour long, but it is dense with material and stories, so much so that I have only touched upon less than half of the documentary. I do not talk about the harrowing stories shared by the women, of the words they use to talk about their experience. I do not talk about Crystal and Esther — a friendship seemingly borne from their experience as sex workers, and their journey together. I cannot properly express what they so excellently tell themselves. Instead, I hope you are curious enough to want to know more, to hear these women tell their stories themselves.

Save My Seoul is filled with the contrasting imagery of South Korea — the Korea that is publicized: pristine clean and a picture of economic might with the traditional culture — anchored by trips to “588,” a red light district, and Miari, the biggest red light district in Seoul. I’m admittedly jaded by this point, due to my studies and my normal research work on sexual and gender-based violence. However, the images presented stay with you days and maybe even weeks later. That is due to the excellent direction and editing by the people behind the documentary.

I highly encourage everyone to see it, if you are able.

(YouTube, Save My Seoul [1][2], UN Office on Drugs and Crime, UN Women, The Korea Observer, Al Jazeera, Images via Jubilee Project)