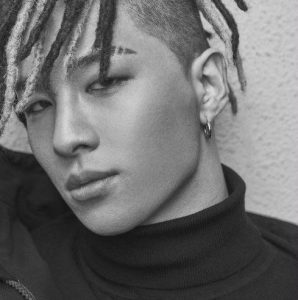

In a time when black bodies are still seen as dangerous creatures to be policed inhumanely; when segregation persists through discriminatory housing policies, and racial profiling chains African-Americans to lengthy prison sentences for possession of marijuana, Taeyang has revealed in Big Bang’s latest photobook:

In a time when black bodies are still seen as dangerous creatures to be policed inhumanely; when segregation persists through discriminatory housing policies, and racial profiling chains African-Americans to lengthy prison sentences for possession of marijuana, Taeyang has revealed in Big Bang’s latest photobook:

“I’m not black, so I’ll probably have to have more experience and go through more pain if I want to express the sentiments, emotions, and soul that black people have through my music. That’s why I believe that pain and suffering will make my music richer.”

The intention here is to be forward-thinking. The intention here is to be open-minded, welcoming of a different set of perspectives. Given that South Korea is a conservative Asian society where interracial dating – particularly with dark-skinned people – is looked down upon, and the bullying of mixed-race children commonplace, Taeyang intends to break with past precedent by publicly embracing the historical taboo of blackness.

But the goodwill and naivety propelling this statement are what makes it so insidious. While Taeyang hopes experiencing the pain of black people will bring new depths to his music, the end result benefits only one man, and points to the appropriation of a whole culture’s suffering for personal gain. It was bell hooks who first theorized this kind of self-righteous desire in consuming blackness as “eating the other,” an act in which a minor ethnicity is commoditized by a dominant power to perpetuate the racial status quo.

hooks attributes this to “the postmodern malaise of alienation,” a sickness that resonates with South Korean society, and K-pop in particular. When people live in a world where perfect images dictate everything – forcing plastic surgery to be the norm, mental health to be stigmatized, and alcoholism and suicide rates to skyrocket – what will jaded youth turn to for authenticity? If hope of redemption through one’s own culture is bankrupt, the new cache of cool shall be mined in the untouched, the foreign, the black. And so we have watched hip-hop be devalued to a mere concept that any group will try on, like a trendy sneaker: you can now listen to Zico rap about his “black soul,” and cringe as Taeyang contorts his paltry locks into a shadow of The Weeknd’s hairstyle.

K-pop isn’t the first to play this game. If anything, it’s followed in the footsteps of stars like Miley Cyrus and Post Malone – white people who momentarily clothe themselves in a costume of drugs, materialism and hypersexuality without facing the consequential discrimination. Given that American music has a long history of fetishizing African-American culture, of course it is white people hooks calls out first and foremost in her work. Where, then, does K-pop fall on a gradient with opposing poles of black and white? On a global scale, perhaps squarely in the middle, part of the East Asian “bourgeoisie” that does not quite have the prestige of the white West, nor the exoticness of developing black and brown countries.

K-pop isn’t the first to play this game. If anything, it’s followed in the footsteps of stars like Miley Cyrus and Post Malone – white people who momentarily clothe themselves in a costume of drugs, materialism and hypersexuality without facing the consequential discrimination. Given that American music has a long history of fetishizing African-American culture, of course it is white people hooks calls out first and foremost in her work. Where, then, does K-pop fall on a gradient with opposing poles of black and white? On a global scale, perhaps squarely in the middle, part of the East Asian “bourgeoisie” that does not quite have the prestige of the white West, nor the exoticness of developing black and brown countries.

But it is this central ground between white and black that can be the most toxic. As writer Mari J. Matsuda reminds us, the racial middle lives in danger of reinforcing white supremacy, of “deluding itself into thinking it can be just like the white if it tries hard enough.” Even as China becomes the largest market in the world, K-pop artists like Taeyang continue to talk about how badly they wish to “gain recognition in the United States” through eerily similar means of appropriation. Lee Soo-man speaks of finessing cultural technology to become the next cultural imperialist, a little brother emulating the elder United States first seen shoving its corporate products down the throats of developing nations.

But while K-pop looks up to American music by emulating its tendency to appropriate, the opposite cannot be said. The reality is that the American market remains vast, fickle, and notoriously difficult to enter. At only 5.6% of the American population, the Asian presence in the United States has generally been noted through the media’s use of yellow face, the stereotype of exotic yet submissive women, and the delegation of emasculated men as the butt of the joke.

For K-pop to mimic the white appropriation of black culture is thus for K-pop to turn a blind eye to its own position of inferiority under the gaze of white America. It is to glamorize the cruelty and carelessness of a nation that has relentlessly appropriated, and mocked, both African-American and Asian culture over the course of its history. It is to forget South Korea’s botched occupation by the United States before the Korean War, an erasure of national suffering that stands as a valid and fruitful source for artistry. Rather than taking cues from white supremacy, and romanticizing the pain of African-Americans to “make music that moves people’s hearts,” Taeyang can and should introspect on the trauma of South Korean history, which already includes the hardship of mixed black Koreans, such as fellow singers Insooni, Yoon Mi Rae and Michelle Lee.

For K-pop to mimic the white appropriation of black culture is thus for K-pop to turn a blind eye to its own position of inferiority under the gaze of white America. It is to glamorize the cruelty and carelessness of a nation that has relentlessly appropriated, and mocked, both African-American and Asian culture over the course of its history. It is to forget South Korea’s botched occupation by the United States before the Korean War, an erasure of national suffering that stands as a valid and fruitful source for artistry. Rather than taking cues from white supremacy, and romanticizing the pain of African-Americans to “make music that moves people’s hearts,” Taeyang can and should introspect on the trauma of South Korean history, which already includes the hardship of mixed black Koreans, such as fellow singers Insooni, Yoon Mi Rae and Michelle Lee.

But long before hip-hop was repackaged for mainstream consumption, there were already Korean rappers adopting rap to discuss contemporary social issues. From Seo Taeji’s early critique of the South Korean education system in “Class Idea,” to J’Kyun’s vicious attack on the Big Three in “If We Go” and San E’s diss at the Korean government in “Bad Year,” these artists have created respectfully, without masquerading in African-American culture. They understood the impetus at the heart of hip-hop to be an outside voice commenting on society – not a slave to the capitalist tendency to produce while perpetuating oppression.

In the end, to succeed in today’s global market is to stand out by acknowledging your place of origin and its effect on your art. Mainstream K-pop’s success thus far has been attributed to its catchy hooks, flashy fashion, and synchronized dances – elements of pop that were adopted from the West, but gleefully retailored to express South Korea’s own coming-of-age story in the ’90s. In contrast, K-pop’s donning of hip-hop today is often its sad mimicry of the American appropriation of African-American culture. It is ultimately an artistic failure to create or innovate.

In the end, to succeed in today’s global market is to stand out by acknowledging your place of origin and its effect on your art. Mainstream K-pop’s success thus far has been attributed to its catchy hooks, flashy fashion, and synchronized dances – elements of pop that were adopted from the West, but gleefully retailored to express South Korea’s own coming-of-age story in the ’90s. In contrast, K-pop’s donning of hip-hop today is often its sad mimicry of the American appropriation of African-American culture. It is ultimately an artistic failure to create or innovate.

As poet Mia You notes, “I like the idea that K-pop…at its origin was a way for the local culture to navigate, to make use of, a dominating external culture; a way for Korea to come to terms with America’s invasiveness and pervasiveness, and to try to set the terms. I have no interest in a K-pop that spits back a glitter-covered and auto-tuned echo of the Empire, just to please it.”

I, too, am nervous of this, but even more so of a K-pop that spits back cheap facsimiles of hip-hop – another satellite of racism, hypnotized by the white American pop empire.

(Huffington Post, The Atlantic, New York Times, bell hooks: “Eating the Other: Desire and Resistance,” Salon, The New Yorker, Youtube [1][2][3][4][5], Mari J. Matsuda: “We Will Not Be Used,” Graduate School of Stanford Business, Billboard, United States Census, Poetry Foundation, Black In Korea, Images via YG Entertainment, Romantic Factory Entertainment)