A few days ago, CéCi magazine announced that they would release a special photo spread of BTS in honor of the publication’s 20th anniversary. The preview pictures looked great, but the costs for the magazine were unreasonable, and adding onto that the costs for shipping … suffice to say I was thankful when the first pictures of the shoot started appearing on the internet. Well, I was at first.

A few days ago, CéCi magazine announced that they would release a special photo spread of BTS in honor of the publication’s 20th anniversary. The preview pictures looked great, but the costs for the magazine were unreasonable, and adding onto that the costs for shipping … suffice to say I was thankful when the first pictures of the shoot started appearing on the internet. Well, I was at first.

Then I decided to open up the pictures to their full size. I couldn’t believe my eyes when I enlarged Rap Monster‘s solo shot and was suddenly confronted with a hat that clearly bears the insignia of the SS (the swastika, eagle, and apparently even the skull below them). SS stands for Schutzstaffel (Protection Squadron), a paramilitary organization which played an essential part in bringing Adolf Hitler to power in 1933. Additionally, the SS was responsible for running the concentration camps all over Europe.

BTS had just recently released teaser pictures for their new tour in which they wore military clothing. Maybe BTS’ staff asked CéCi to include this theme in the photo shoot. Obviously someone at CéCi thought it was okay to use symbols associated with some of the most atrocious crimes committed in the 20th century for that. At first glance, it seems baffling.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RkaSnMdR0BI]This is actually not a completely new occurrence though. During SPEED‘s promotions for “Don’t Tease Me” earlier this year, member Se-joon wore an outfit alarmingly similar to outfits worn by National Socialists during the Forties, even down to the red armband on some occasions.

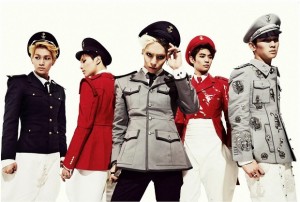

Let’s also not forget SHINee‘s outfits for “Everybody”. While the similarities here are more vague, many international fans still couldn’t shake off an uncomfortable feeling when seeing Jonghyun and Key in those grey suits.

Yet another example is that of singer Yim Jae-beom, known for his appearance on I Am a Singer, who performed in 2011 wearing a Nazi uniform (judging by the hat, it is once again an SS uniform). According to his own statements, the performance was meant to be understood as a criticism of war and dictatorial regimes. Why he couldn’t think of another way to display this criticism remains unknown.

Now, what are all these examples meant to prove? Do I think all the aforementioned performers are neo-Nazis, consciously glorifying the mass murder of Jewish people, Sinti and Roma, homosexuals, political dissidents and others? No, absolutely not. What it shows though is that there seems to be an acute lack of awareness regarding the amount of meaning affiliated with such symbols and uniforms.

Now, what are all these examples meant to prove? Do I think all the aforementioned performers are neo-Nazis, consciously glorifying the mass murder of Jewish people, Sinti and Roma, homosexuals, political dissidents and others? No, absolutely not. What it shows though is that there seems to be an acute lack of awareness regarding the amount of meaning affiliated with such symbols and uniforms.

In a way, that is completely understandable: The European part of the war had very little to do with South Korea. It was a war happening on another continent, while the Korean population had to endure the much more immediate oppression from the Japanese occupying forces. Maybe German National Socialist symbolism isn’t known in detail to younger Korean generations. A well-meaning observer will understand that singular slip-ups like that can happen.

But reports from South Korea seem to indicate that there is nothing singular about the careless use of Nazi insignia shown in CéCi’s case. “Nazi chic”, the aesthetic appreciation of Nazi fashion and paraphernalia, is an actual thing happening in the country: As just one of a few examples from the world of advertisement, there was a cosmetic company which alluded to World War II and once again the SS in particular in a TV ad in 2008. The slogan for their product before they were forced to change it? “Even Hitler didn’t unite the East and West.” But apparently their skin care product does.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wdbpb5IDEZU]Korean cosplayers also seem to embrace the perceived snazziness of the Nazi uniforms. Well, they were produced by the company which later would become famous under the name of Hugo Boss after all. A titillating mix of genocide and high fashion coming to a store near you. Who cares what happened seventy years ago, right? That’s so nineteenhundred-and-late.

By far the most popular way of indulging in this fascination with Nazism seem to be bars. A first account appears in an edition of the Korean Times in 1988, in which an expat is criticizing the existence of a bar called “Gestapo” in Itaewon, Seoul. In the early 2000s, other accounts talk of a “Hitler” bar in Busan and the “Fifth Reich” (formerly called “Third Reich”) bar in Seoul, among others. With pictures of Hitler and diverse Nazi-related items constituting the interior design, they offer an opportunity for a different night out for those who like the shock value. “[A]t least they dressed well”, one of the patrons tells the visiting reporter. That’s one way of looking at it.

Arguably, this is not a phenomenon exclusive to South Korea. Thailand and Japan have also seen a fascination of a certain part of their population with this so called “Nazi chic”. Prince Harry, a British royal, thought it would be fun to dress up as a Nazi for a party in 2005 — and he was born in a country terribly affected by the German military during World War II.

Arguably, this is not a phenomenon exclusive to South Korea. Thailand and Japan have also seen a fascination of a certain part of their population with this so called “Nazi chic”. Prince Harry, a British royal, thought it would be fun to dress up as a Nazi for a party in 2005 — and he was born in a country terribly affected by the German military during World War II.

People might argue that wearing National Socialist clothing, or collecting paraphernalia associated with it, due to an aesthetic interest is still better than doing so because of political conviction. But if there is an opportunity to convey to people the actual meaning attached to the clothing that they are wearing, I think it would be preferable if they stopped wearing and appreciating these items altogether.

SS uniforms are not a fashion statement or a thrilling transgression of societal borders. The swastika, in the context of its use in National Socialist Germany, represents genocide and unspeakable crimes against humanity. Furthermore, the Nazis were allies of the Japanese, whose rule is still a painful memory for many Korean people.

However it came to be made, let’s not use that hat anymore, CéCi. Let’s be careful with military concepts in the future, South-Korean entertainment industry. This German fan will appreciate it very much.

(YouTube[1][2][3][4], Wikipedia[1][2][3][4][5], Asia Obscura, The Korea Times, One Free Korea, Gusts of Popular Feeling, Pusan web, TIME. Images via CéCi magazine, SM Entertainment, Core Contents Media)