Neon skater skirts meet pale peach dresses. Benevolent Forever21 fights it out with snooty Gucci. Dandies of Gangnam brush shoulders with hipsters of Hongdae, while 2NE1 and SNSD create rigid codes of opposing femininities. Marketing this seemingly inclusive fashion scene to its domestic and international consumers is part of a billion dollar industry, and magazines are one of its most potent tools. Anyone who enjoys the For Your Viewing Pleasure posts has firsthand experience of its effect.

Neon skater skirts meet pale peach dresses. Benevolent Forever21 fights it out with snooty Gucci. Dandies of Gangnam brush shoulders with hipsters of Hongdae, while 2NE1 and SNSD create rigid codes of opposing femininities. Marketing this seemingly inclusive fashion scene to its domestic and international consumers is part of a billion dollar industry, and magazines are one of its most potent tools. Anyone who enjoys the For Your Viewing Pleasure posts has firsthand experience of its effect.

Vogue Girl, GQ Korea, Elle Korea — these magazines should strike more than a chord as they are recurring names in the fashion scene. Being more or less transnational, these magazines — with their centres in the West -– aim at creating and marketing “global” narratives to build a stronghold throughout international markets. However, one magazine deviates from the norm: CéCi.

K-pop and fan consumerism

Controlled by J Contentree Corporation, the largest media group in South Korea, CéCi, with the tagline “20s Best Friend,” is a fashion magazine with a target audience of upper middle class women in their 20s. A completely Korean enterprise with the highest circulation, it only recently expanded and branched into China (2008) and Thailand (2012). Clearly, CéCi is doing something right compared to its contemporaries, and a quick look at its covers reveals a difference in approach.

In the second half of 2013 alone, six covers featured either a Korean actress or a female K-pop idol; Lee Seung-gi was also the only male actor featured in their 19th anniversary edition. On the other hand, Vogue Girl – under Conde Nast — featured only female Caucasian models in the second half of 2013. CéCi does not need to pander to international markets; its only concern is Korean citizens, and, hence, their sole purpose is to make their covers relatable so that anyone who looks at it can feel that this magazine is only for them, and that the magazine takes care of their specific “Korean” needs. Having native citizens on the cover creates an illusion of ‘real’ and accessible beauty; in comparison to the light-haired, light-eyed, light-skinned models, it becomes less unreal. It’s almost like a national magazine.

However, an audience of 20-something women can’t possibly be the only driving force behind their massive sales. This brings into frame their major consumers: fans.

Featuring K-pop idols in almost rapid succession means that they’re advertising faces well-known to the domestic and international fandom. The cover exceeds the value of the magazine, becoming an artifact in its own right, gaining exclusive importance as part of a collection. While financially dependent, most fans are far more zealous than fashion consumers and hence, end up becoming a lucrative and unsuspecting market for CéCi. The magazine is not a flimsy leaflet but a 500-600 page matte finish monstrosity with around 45%-50% dedicated to advertisements that feature idols on occasion. The point is no one will buy such a magazine solely for entertainment purposes, or merely to flip through it. It’s an investment of time, money and space, and only fans are dedicated enough to make that investment.

Cover treatment

The cover page, as hinted to before, is arguably the most important part of any magazine. It’s the one that grabs attention and lures consumers, and therefore, it has to be meticulously chosen and carefully designed. CéCi tries to bridge the gap between infantilization and hyper-sexualization unlike, say, InStyle (J Contentree), which is more inclined to use “sexy” covers and spreads that are more unseemly than seductive to its target audience. Most CéCi covers do not have out of context or blatantly objectifying skin showing. Artists look straight at the camera instead of looking at it over their shoulder. While there aren’t many covers with the artists’ hands on their waist, the little that do also feature the women standing with their legs apart, maybe with a smile or with a brooding look — the pose doesn’t play in as a compulsory accessory for some “women’s empowerment” edition. This isn’t to say that their covers are conceptually flawless; it’s simply quite different from a host of international magazines.

The cover page, as hinted to before, is arguably the most important part of any magazine. It’s the one that grabs attention and lures consumers, and therefore, it has to be meticulously chosen and carefully designed. CéCi tries to bridge the gap between infantilization and hyper-sexualization unlike, say, InStyle (J Contentree), which is more inclined to use “sexy” covers and spreads that are more unseemly than seductive to its target audience. Most CéCi covers do not have out of context or blatantly objectifying skin showing. Artists look straight at the camera instead of looking at it over their shoulder. While there aren’t many covers with the artists’ hands on their waist, the little that do also feature the women standing with their legs apart, maybe with a smile or with a brooding look — the pose doesn’t play in as a compulsory accessory for some “women’s empowerment” edition. This isn’t to say that their covers are conceptually flawless; it’s simply quite different from a host of international magazines.

CéCi treats its cover boys differently, too. Lee Min-ho, Lee Seung-gi, Block B, etc. have been featured wearing suits against a white background. Lee Min-ho was also photographed against an aquamarine background, and all these images have been full body shots. All male covers have either been full body or head-to-torso shots — rather than zone in on a headshot, the subjects’ bodies have been featured at all costs. A consumer is then allowed to judge the face, the body frame, and the clothes for all they’re worth.

Compare this to men’s magazines like Gentleman (J Contentree) and GQ Korea (Conde Nast), and one finds a drastic difference. The covers are focused on the pensive or indifferent faces of hyper-masculine older men, always against dark tones, and more often than not, with facial hair. When they’re shown along with their bodies, they’re invariably given a context in the form of some obscure object or a room. They’re not models -– they are either portraits or men at work, and not subject to judgment, and most importantly, they need to be appealing to other men around the world. Maxim Korea is a horror show of its own — it looks more like a lingerie fashion magazine than a men’s publication — with its aggressive stance on heterosexuality.

Pictorials and spreads

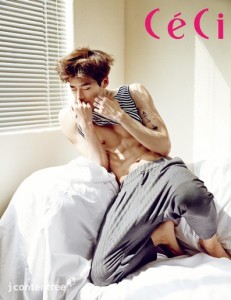

If CéCi plays safe with its covers, then it lets loose with its pictorials and spreads. CéCi has had more ‘concept’ spreads of men than women, and attempts quite consciously at redefining masculinity. It doesn’t go for a hyper-masculine approach, and it doesn’t feminize the male body completely, as was the case with Vogue Girl’s SHINee spread. Rather, it tries to blend in the two with an overt aggressive heterosexuality and implicit passive homosexuality. The spreads with Lee Jong-suk, EXO and Donghae are only few such examples.

Lee Jong-suk, in the April 2014 edition, is shown to have a chiseled body with a baby face and tousled hair, but he doesn’t look at the camera except once. The fact that he has woken up — that he is dazed and confused and hence vulnerable — makes the pictures seem candid. Here, the soft masculinity is sustained by his face and his “original” personality. There is nothing powerful or aggressive about this pictorial. Gentility is furthered by another semi-naked photo shoot of Donghae in the September 2012 edition titled “Stolen Afternoon.” Donghae is not shown as conscious of his nakedness; he is neither proud nor ashamed of it. The pictorial is supposed to show a man’s afternoon, but it has him loitering around, reading a comic, and eating junk food – nothing quite “manly,” everything quite boyish instead.

Lee Jong-suk, in the April 2014 edition, is shown to have a chiseled body with a baby face and tousled hair, but he doesn’t look at the camera except once. The fact that he has woken up — that he is dazed and confused and hence vulnerable — makes the pictures seem candid. Here, the soft masculinity is sustained by his face and his “original” personality. There is nothing powerful or aggressive about this pictorial. Gentility is furthered by another semi-naked photo shoot of Donghae in the September 2012 edition titled “Stolen Afternoon.” Donghae is not shown as conscious of his nakedness; he is neither proud nor ashamed of it. The pictorial is supposed to show a man’s afternoon, but it has him loitering around, reading a comic, and eating junk food – nothing quite “manly,” everything quite boyish instead.

Finally, EXO solidifies the image of the appealing heterosexual masculinity — a gentle and soft boyish man — with their “Wild and Mild” spread. The BTS video is actually more interesting than the magazine itself, for while the boys look frail holding stalks of flowers with the female photographer clicking away, the background song has the lyrics — “I want you to kiss me/Let your tongue, Let your mouth become” — sung in a husky voice. This reveals an aggressive heterosexuality in terms of sexual knowledge, but the difference is that the man will not take charge. He will seduce, allure, and insinuate ideas — just like the spreads do — but the final work has to be done by the consumers. He, therefore, functions both as the passive desiring subject and the desired object.

Heterosexuality and masculinity

Most of the world, including South Korea, still sanctions only heterosexuality, and by the way women seem to consume CéCi’s material so voraciously, one would be inclined to believe that these representations of masculinity are actually the ideal. However, as “duh!” as it may seem, it is not quite so when magazines for men come into the picture.

Welcome, brawny men on covers and few spreads which invariably have dark tones, random spreads on wines, cars, sports – lifestyle, and women, lots and lots of barely clothed women. There are a select number of spreads on men, muscular and seemingly sophisticated. No young boys can be found here. There is a certain degree of self-consciousness, as if it’s forbidden to play around except in spreads featuring women. Again, women are not given any context. CL’s photoshoot for GQ Korea is one such example. Looking at the picture won’t give us a sense as to why is CL doing whatever she is doing. The dripping coke, the boxing gloves (a traditionally masculine sport) all built into a hyper-sexualised image of her.

Minah’s pictorial (right) infantilizes her completely, representing her as an unaware girl with her legs spread on a bed surrounded by toys. Hyung-sik’s pictorial, on the other hand, has him lying on a red car. This represents a very different kind of masculinity; masculinity actively imbibed and endorsed by rich, urban, heterosexual men. It consciously excludes the population of homosexual men by constantly reiterating that the perfect man needs to like women, a certain kind -– fair, slim, sexually attractive. This brings the question as to who decides what’s masculine. If heterosexual femininity is based on male validation, heterosexual masculinity is also based on male validation.

Minah’s pictorial (right) infantilizes her completely, representing her as an unaware girl with her legs spread on a bed surrounded by toys. Hyung-sik’s pictorial, on the other hand, has him lying on a red car. This represents a very different kind of masculinity; masculinity actively imbibed and endorsed by rich, urban, heterosexual men. It consciously excludes the population of homosexual men by constantly reiterating that the perfect man needs to like women, a certain kind -– fair, slim, sexually attractive. This brings the question as to who decides what’s masculine. If heterosexual femininity is based on male validation, heterosexual masculinity is also based on male validation.

This is where CéCi’s implicit passive homosexuality plays in. CéCi’s version of masculinity is not the hegemonic masculinity of physical and sexual aggression, and emotional indifference. Neither does it claim to be the guide to ultimate manhood – something which men’s magazines do – instead it tries to show a variety of lesser known masculinities, not only in terms of physicality but also in terms of social marginality. Hence, a variety of men get represented in it with neither of them claiming to be the ultimate. Secondly, by showing the sexual availability of passive men it recognizes female sexuality but also implicitly makes way for the male homosexual consumer. Of course, CéCi doesn’t claim that these men are for homosexual consumption but it doesn’t actively deny it either.

The CéCi factor

This is not to say CéCi is a supporter of homosexuality or even understands it, but the magazine is a clever marketing tool that can be used to tap into any potential audience. If men’s magazines have cut out on their homosexual audience by featuring only semi-naked women, then CéCi redirects that audience and the immense financial profits with it towards its subversive masculinity spreads.

CéCi is not a revolutionary magazine. It still adopts tropes and strategies that sell unrealistic ideas of beauty and femininity, and it reinstates gender roles with equal ferocity as any other magazine. But it stands as an example of how local magazines, not expected to appease Western markets or ideologies, have enough power and capability in creating new definitions and new power structures, not necessarily with the intention of toppling the current head but rather warning it that it’s not the only norm, the only reality. People do have alternatives, and there is a massive market for these lesser known alternatives.

(YouTube; images via CéCi, GQ Korea, Vogue Girl)