Within the past few years, the word “Hallyu” has become a used and abused term, to the point where the word itself no longer has a standard definition, but has come to mean different things in different countries. At its most basic level, the Hallyu phenomenon represents the spread of Korean popular culture in countries other than Korea. From there on in, however, the specific definition of Hallyu changes depending on the country in question. In many East and Southeast Asian countries, Hallyu has become embedded within mainstream popular culture and music. On the other hand, Korean pop remains a niche interest in European and North American countries, with little widespread popularity to be seen.

Within the past few years, the word “Hallyu” has become a used and abused term, to the point where the word itself no longer has a standard definition, but has come to mean different things in different countries. At its most basic level, the Hallyu phenomenon represents the spread of Korean popular culture in countries other than Korea. From there on in, however, the specific definition of Hallyu changes depending on the country in question. In many East and Southeast Asian countries, Hallyu has become embedded within mainstream popular culture and music. On the other hand, Korean pop remains a niche interest in European and North American countries, with little widespread popularity to be seen.

The Hallyu effect in Japan, however, proves to be an interesting case. As evidenced by actors like Bae Yong-joon and Lee Byung-hun, as well as singers like BoA and DBSK — all who have become household names in Japan — it seems that Korean entertainment labels have always taken special care when promoting their artists in the Japanese market. While the Hallyu phenomenon was first identified in China and Taiwan in the late 90s (by Chinese scholars rather than Korean scholars, no less), it can be argued that Hallyu wasn’t a “big deal” to Korea until 2002, when Winter Sonata gained considerable popularity in Japan. From then on, it seemed as if Korean entertainment companies realized that they, too, had a shot at gaining a foothold in the prized Japanese market, but in order to do so, they had to proceed with caution.

The amount of detail and dedication required to maintain BoA and DBSK’s Japanese careers reflects this cautious attitude to a T. SM did not regard success in Japan as something to be conquered, but as something to be earned. BoA and DBSK debuted in a time when Hallyu was still a relatively new phenomenon and nothing was to be taken for granted. Generally speaking, Japan was (and still is) regarded with admiration and intimidation by many Asian countries in ways that spilled outside the realm of the entertainment industry. This fear has its roots in history, and to this day, many people in China and Korea regard Japan with a sense of both awe and loathing. It’s a complex phenomenon, but it does explain the intimidation and air of “untouchability” that Japan radiated, even after the success of Winter Sonata.

That said, BoA and DBSK could not rely on their popularity in Korea to propel themselves forward in Japan, because this was a time when the popularity of Korean pop culture wasn’t enough to do any “propelling” of any sort. SM knew this, and thus concluded that the only way that a Korean artist could make a name for themselves in Japan in that kind of environment is to play on the same field as all the other Japanese artists. And play they did; five years of hard work later, BoA was topping the Oricon charts and DBSK was performing at Tokyo Dome — but more importantly, both BoA and DBSK received the same level of respect from industry officials and the public as any other Japanese artist of equal caliber.

That said, BoA and DBSK could not rely on their popularity in Korea to propel themselves forward in Japan, because this was a time when the popularity of Korean pop culture wasn’t enough to do any “propelling” of any sort. SM knew this, and thus concluded that the only way that a Korean artist could make a name for themselves in Japan in that kind of environment is to play on the same field as all the other Japanese artists. And play they did; five years of hard work later, BoA was topping the Oricon charts and DBSK was performing at Tokyo Dome — but more importantly, both BoA and DBSK received the same level of respect from industry officials and the public as any other Japanese artist of equal caliber.

It’s easy to look at BoA and DBSK’s success and say that this is how all Japanese debuts should be done. In many ways, this claim is legitimate; BoA and DBSK not only put out some of their best material in Japan, but their harsh careers in Japan also helped them become better artists and performers in the long run. The results from BoA and DBSK’s hard work in Japan are undoubtedly positive, which is perhaps why BoA and DBSK have become the role models of almost every K-pop artist who is currently trying to make it in Japan. But though these new artists hold BoA and DBSK’s work in such high regard, why is it that nearly every K-pop artist is releasing cheap Japanese-language remakes of their old Korean singles in the Japanese market, and more importantly, why are these K-pop artists still respected in the Japanese music industry?

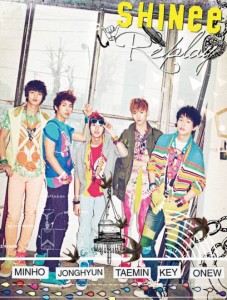

In the time between BoA and DBSK’s debut and now, a lot has changed about Hallyu and its level of influence across Asia. What started out as a mere cultural observation by a few Chinese journalists has since evolved into a huge cultural phenomenon that is prevalent in almost all parts of Asia and beyond. And Japan hasn’t been impervious to the change. While Japan still maintains a very strong and powerful entertainment industry of its own, there is a growing K-pop fanbase on Japan’s shores all the same, and this fanbase is oftentimes no different than the K-pop fan circles found in China or Singapore or the Philippines. Within the past few years, Japan has also become a customer of Hallyu, with a buyer demographic that is really no different than that of any other Asian country. K-pop has the same kind of appeal in Japan that it has in nearly every other Hallyuified Asian country — SHINee sold 24,000 tickets to their all-Korean material concert at Yoyogi National Gymnasium even before their official Japanese debut. Unlike before, where Korean artists had to fully integrate themselves in the Japanese music industry in order to have a chance at success, Japan has become a Hallyu-friendly region where K-pop artists can make a name for themselves simply by riding the Korean Wave. And there’s lots of money to be made in Japan, which is the reason why so many Korean entertainment companies have made Japan their target foreign market of choice and the reason why K-pop artists continue to debut in Japan and profit from the sale of Japanese-language singles that are no different from their Korean counterparts.

In the time between BoA and DBSK’s debut and now, a lot has changed about Hallyu and its level of influence across Asia. What started out as a mere cultural observation by a few Chinese journalists has since evolved into a huge cultural phenomenon that is prevalent in almost all parts of Asia and beyond. And Japan hasn’t been impervious to the change. While Japan still maintains a very strong and powerful entertainment industry of its own, there is a growing K-pop fanbase on Japan’s shores all the same, and this fanbase is oftentimes no different than the K-pop fan circles found in China or Singapore or the Philippines. Within the past few years, Japan has also become a customer of Hallyu, with a buyer demographic that is really no different than that of any other Asian country. K-pop has the same kind of appeal in Japan that it has in nearly every other Hallyuified Asian country — SHINee sold 24,000 tickets to their all-Korean material concert at Yoyogi National Gymnasium even before their official Japanese debut. Unlike before, where Korean artists had to fully integrate themselves in the Japanese music industry in order to have a chance at success, Japan has become a Hallyu-friendly region where K-pop artists can make a name for themselves simply by riding the Korean Wave. And there’s lots of money to be made in Japan, which is the reason why so many Korean entertainment companies have made Japan their target foreign market of choice and the reason why K-pop artists continue to debut in Japan and profit from the sale of Japanese-language singles that are no different from their Korean counterparts.

And there’s really nothing wrong with that.

Considering the climate of Hallyu in Japan today, there’s really no need for Korean artists to do a BoA/DBSK-styled debut anymore. In fact, to debut a la BoA/DBSK would be rather silly. The conventional route for Korean artists to debut in Japan has already been established, and it would be strange for a K-pop artists to deviate from that convention and make more trouble for themselves without any guarantee of success.

K-pop and J-pop fans alike seem to be disgruntled over the simplistic and ‘lazy’ approach that many K-pop artists have taken in Japan, but this disgruntlement seems to lie in the belief that the Japanese market deserves special treatment. This ‘special treatment’ might have been deserved and necessary back in the early-mid 2000s when Hallyu was still a budding phenomenon, but not anymore. There was once a time when Japan was held as an unattainable goal for Korean entertainers, but that is no longer the case. As far as Korean entertainment is concerned, Japan has been swept up by Korean fan culture all the same — and that is more than enough for K-pop to establish a solid footing in the Japanese market.

K-pop and J-pop fans alike seem to be disgruntled over the simplistic and ‘lazy’ approach that many K-pop artists have taken in Japan, but this disgruntlement seems to lie in the belief that the Japanese market deserves special treatment. This ‘special treatment’ might have been deserved and necessary back in the early-mid 2000s when Hallyu was still a budding phenomenon, but not anymore. There was once a time when Japan was held as an unattainable goal for Korean entertainers, but that is no longer the case. As far as Korean entertainment is concerned, Japan has been swept up by Korean fan culture all the same — and that is more than enough for K-pop to establish a solid footing in the Japanese market.

But with this phenomenon comes a certain loss. As aforementioned, the road for Korean entertainers in Japan has been established, and it is difficult (if not pointless) for a Korean artist to attempt to enter the Japanese market in any other way. Therefore, it has become virtually impossible for a Korean artist to debut in Japan in the same way as BoA and DBSK and enjoy the same level of success. Groups like DGNA the Boss and Supernova both tried to debut in Japan in the same way as DBSK and BoA, but they have been deemed ‘flops’ in comparison to the hordes of other K-pop artists in Japan who are surfing high on the Korean Wave. And that’s a real shame, because it’s almost indisputable that BoA and DBSK’s works in Japan are far less superfluous and far more substantial than the constant remakes and Hallyufied success that K-pop artists are now restricted to. As it currently stands, K-pop is locked into its own Hallyufied, fandomized niche of Japanese culture, where the hard work and detail put into BoA and DBSK’s careers wouldn’t only be unnecessary, but inefficient. The result? Korean idols will be penned into their own “Hallyu” box, with little hope of ever really meshing with the rest of the Japanese music industry.

But one should make the most of every situation, and Korean entertainment companies should take care in maximizing the quality of their products whenever possible. Unfortunately, this hasn’t been the case. When working in Japan, one should try to work with Japanese staff and produce songs written by Japanese composers to maximize the chances of achieving an aesthetic that is, at the least, reminiscent with the aesthetic of the current Japanese music scene. SNSD has done a relatively good job of this, as their Japanese album was produced by Japanese staff and their MVs are clearly shot in a very J-poppish style. But other groups such as SHINee and U-Kiss seem to be taking songs that would normally go on any other Korean record, creating Japanese lyrics, and slapping the tracks onto a Japanese album or single. The composition credits on SHINee’s first Japanese album are filled with the names of Swedish composers — the same composers that SM routinely employs for their artists’ Korean releases. Korean entertainment companies have complete control over their artists’ material, if nothing else. But the fact that there’s virtually no distinction between SHINee’s Korean material and Japanese material is very disheartening.

But one should make the most of every situation, and Korean entertainment companies should take care in maximizing the quality of their products whenever possible. Unfortunately, this hasn’t been the case. When working in Japan, one should try to work with Japanese staff and produce songs written by Japanese composers to maximize the chances of achieving an aesthetic that is, at the least, reminiscent with the aesthetic of the current Japanese music scene. SNSD has done a relatively good job of this, as their Japanese album was produced by Japanese staff and their MVs are clearly shot in a very J-poppish style. But other groups such as SHINee and U-Kiss seem to be taking songs that would normally go on any other Korean record, creating Japanese lyrics, and slapping the tracks onto a Japanese album or single. The composition credits on SHINee’s first Japanese album are filled with the names of Swedish composers — the same composers that SM routinely employs for their artists’ Korean releases. Korean entertainment companies have complete control over their artists’ material, if nothing else. But the fact that there’s virtually no distinction between SHINee’s Korean material and Japanese material is very disheartening.

Japan is a unique market for K-pop in many ways, but not because it’s deserving of any kind of special treatment or elevated respect above that of any other Asian market. It’s unique because it’s an extremely profitable market, and many Korean entertainment companies have chosen to release exclusive material in Japan in order to maximize this profit margin. But apart from that, the climate of Hallyu in Japan has changed, and while the thought of more Korean artists like BoA and DBSK making a respectable name for themselves in Japan is an appealing one, it’s not necessarily possible in this current day and age. Rather than berating Korean entertainment companies for their ‘cheapness,’ perhaps it would be wiser to consider Hallyu’s current flow in the Japanese market and the ways that are currently most efficient for Korean entertainment companies to make the best of their investments in Japan.