EXP Edition are rather infamous right now, in the way only a non-Korean Korean band can be. Formerly EXP, the creation of EXP Edition was documented as part of the “I’m Making A Boy Band” thesis project by Bora Kim, in conjunction with Karin Kuroda and Samantha Shao. The current lineup of EXP Edition consists of Hunter Kohl, Koki Tomlinson, Frankie Daponte Junior and Sime Kosta. But the question on everyone’s mind is: can a group of non-Koreans actually create K-pop?

EXP Edition are rather infamous right now, in the way only a non-Korean Korean band can be. Formerly EXP, the creation of EXP Edition was documented as part of the “I’m Making A Boy Band” thesis project by Bora Kim, in conjunction with Karin Kuroda and Samantha Shao. The current lineup of EXP Edition consists of Hunter Kohl, Koki Tomlinson, Frankie Daponte Junior and Sime Kosta. But the question on everyone’s mind is: can a group of non-Koreans actually create K-pop?

Fans who are against EXP Edition’s foray into K-pop make some good points; clearly, these men are not Korean. At the beginning of the project, they spoke little to no Korean, and while they have been studying and released “Feel like this” in Korean, their language use and pronunciation is stilted and unnatural. It’s unclear exactly how much cultural knowledge they have, but it ‘s unlikely to measure up to Korean-born idols, or foreign-born idols trained by Korean companies.

Furthermore, this group skips over some of the things that idols have the hardest; unlike our favourite groups, they haven’t lived through strict training regimes for years, and they aren’t locked into a “slave contract,” as some refer to it. By dint of being American and being formed in the US, EXP Edition simply doesn’t have the same cultural ideas around work, training and relationships. Their earlier videos were heavily criticised for their dancing and seen as not as cohesive and rehearsed as a “real” K-pop group. For obvious reasons, they don’t have the same ability and input that our “normal” K-pop groups do in regards to social media presence and participation in variety shows, due to their limited language skills.

When articulating the reasons for opposition, other common arguments arise: Why should “white” people be allowed a free pass to the Korean music industry when Korean idols have tried for so long to break into the US music scene? In the US and Western media, Asian actors and actresses are often passed over for roles or whitewashed, even in roles that should have been played by Asian characters. When they are given roles, they’re often minor and stereotypical.

When articulating the reasons for opposition, other common arguments arise: Why should “white” people be allowed a free pass to the Korean music industry when Korean idols have tried for so long to break into the US music scene? In the US and Western media, Asian actors and actresses are often passed over for roles or whitewashed, even in roles that should have been played by Asian characters. When they are given roles, they’re often minor and stereotypical.

Other fans were annoyed at seeing them jumping on the bandwagon, especially in their original incarnation as EXP, which was seen as copying Exo, despite the group stating their name came from the word “Experiment”. This prompted the name change to EXP Edition. Finally, while some are not offended per se, they simply do not, and will never, view the group as “K-Pop”.

This said, there are a number of reasons to counter these arguments. Accused of whitewashing K-pop, the group originally had two African-American members, Tarion and David, and current members have heritage including Japanese, Croatian and Chinese. It’s still not Korean, but is it whitewashing? And is appropriation a no-no? Some argue that since K-pop openly appropriates US culture, in particular African-American culture, it’s immensely hypocritical for people to object about appropriation of K-pop. Furthermore, as Korean media can be extremely racist and even still use blackface, these ideas about non-Koreans in K-pop become more complex and difficult to justify.

A number of critics of EXP Edition don’t actually realise that three Asian women — Kim, Kuroda and Shao — created this as an explicit project to explore cultural and social attitudes. Focusing on the central idea of Asian masculinity and masculinity in different cultures, they explore the effects of men wearing makeup, perceptions and objectification of idols, and idol types which fans are attracted to, as well as intercultural communication. Members had weekly practices and Korean language classes to prepare for their eventual debut, even moving to Korea to gain more knowledge of the culture and language they were performing in. Kim, Shao and Kuroda also held a “cuteness workshop” for the group and monitored their reactions — something quite different to what EXP Edition members had previously experienced.

“Here, as a default, you are supposed to present yourself as a strong person. But in Korea and in a lot of Asian countries, it’s better to be friendly. And acting cute is a way of putting yourself in a lower position, so you won’t appear to be too macho or threatening.”

In the meantime, Kim, Kuroda and Shao were discussing important issues around the creation of their band — what is K-pop? What is it about K-pop that makes it K-pop? Is it the language? The location? The cultural references? Is it the ethnic background of the band members? Is it the ethnic background of the producers? Interestingly, Kim points out that the things which cause some Koreans to look down on K-pop, the highly produced, commercial nature and the lack of traditional Korean material, are also some of the things which have made K-pop so popular internationally. When the project blew up in the media, they were surprised and taken aback to find 7000-8000 comments on Instagram, some quite offensive. It seemed that fans had very strong feelings about K-pop, and in Kim’s mind, wanted to keep it Korean, or Asian, at the very least.

We can see some similarities to EXP Edition with Chad Future, another notorious non-Korean trying to break into the K-pop industry. Originally trying to access the market through failed group Heart2Heart , Chad Future then adjusted his target. He created multiple English covers of famous Korean songs and befriended idols before collaborating, notably with VIXX’s Ravi, starting heated online debate about whether he had the right to a place in the industry. Duo CoCo Avenue, also non-Korean, began as part of a K-pop cover group, and progressed to releasing a song in Korean.

So who exactly gets to decide what cultural appropriation is, and whether it’s permitted? Does EXP Edition get a free pass because of Bora Kim’s Korean connections? There seems to be a lot of commentary by Western fans, but how do Koreans feel? It’s also worth noting fans are not asking “Have they made an effort?” so much as “Have they made enough of an effort?”

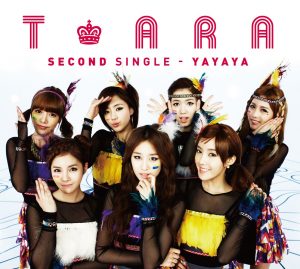

Before giving an opinion on cultural appropriation, fans should also consider whether they would fall into the category of “victims” of appropriation. For example, if a Native-American person has objections to T-ara’s “Yayaya”, before you disagree, ask yourself: “Am I Native-American?” If no, then ask yourself: “Did I actually listen in good faith to what Native-American people were saying about this?” Sadly, it’s common for those who are not actually affected to unthinkingly say “It’s fine!” without actually listening to those who are affected. On the one hand, we could ask ourselves “If this was me in a comparable situation, how would I feel?”, but often, if we’re steamrolling over others’ objections, we’re probably not doing much empathising anyway.

What makes it more complex is that even within groups of affected people, there won’t necessarily be agreement. Some Native-Americans may think it’s truly offensive, some may shrug and say it’s fine. On difficult issues, people don’t always agree, and one fan is not representative of an entire cultural background. Fans should also question whether they are coming from a position of expertise — for example, “Do I know anything about Native-American culture?”. If not, why comment? It’s a little like going to a doctor — everyone has an opinion on medicine, but the people whose opinions we value are those with expertise and credentials.

Ultimately, K-pop fans should ask themselves, “If I am angry at EXP Edition doing this, am I also angry when K-pop groups do this to others?” If not, why not? The questions can be difficult to answer, and even uncomfortable, but worthwhile. Whether you think this deliberate cultural appropriation is acceptable or not, if we’re having this conversation then Bora Kim has succeeded in her goal.

(Columbia University, NBC News [1] [2], Vice, Kore, YouTube [1] [2] [3], Images via MBK, Collab, Jellyfish Entertainment, CoCo Avenue Music)