A few of the members from Girl’s Generation recently proclaimed that they’d like to be regarded as artists. The K-pop universe reacted with a cold and cryptic “No!“– a “No!” that reverberated with overwhelming criticism, skepticism, and cynicism. The response was harsh, but in an effort to understand their artistic desire, SNSD made me think about how idols can transition to becoming artists.

A few of the members from Girl’s Generation recently proclaimed that they’d like to be regarded as artists. The K-pop universe reacted with a cold and cryptic “No!“– a “No!” that reverberated with overwhelming criticism, skepticism, and cynicism. The response was harsh, but in an effort to understand their artistic desire, SNSD made me think about how idols can transition to becoming artists.

Most idols are not considered artists because the term “artist,” in its musical definition, not only describes a person who works in the performing arts — but, more importantly, our interpretation of someone who creates and administers control over their music and image. “Artist” in its Western interpretation is not associated with the Eastern definition of “idol,” a term that unique to the common parlance of East Asian entertainment industries. K-pop fans have learned to separate the two terms based on how they perceive idols and categorize their music–always emphasizing the difference between idols and “real” artists in Korea and abroad. With a respected distinction reserved for artists, more idols are vocalizing that they’d like to be regarded as such, but with the odds against them, how is it possible for idols to make the transition? Why is it better to be labeled an artist than an idol? And why do idols need to become artists?

Based on research and a few years worth of experience with K-pop, there are certain criteria one must meet to be considered an “artist” including, but not limited to: becoming a soloist, composing, producing, and arranging music, getting older, and exercising control over your image.

One of the most famous examples of idol turned artist is Lee Hyori. A combination of image control, age, and becoming a solo artist after a successful run as a girl-group member has transformed Hyori’s place in K-pop. After her stint with popular idol group Fin.K.L. from 1998-2002, she became a successful solo artist, releasing four albums and becoming the highest paid female singer in Korea, with a 3 year contract worth over 2.2 billion won. Hyori has had a huge impact on the South Korean music industry with her brand of confident sex appeal and catchy music. For her undeniable contribution and for being a formidable force in the industry, she has been labeled a K-pop queen.

One of the most famous examples of idol turned artist is Lee Hyori. A combination of image control, age, and becoming a solo artist after a successful run as a girl-group member has transformed Hyori’s place in K-pop. After her stint with popular idol group Fin.K.L. from 1998-2002, she became a successful solo artist, releasing four albums and becoming the highest paid female singer in Korea, with a 3 year contract worth over 2.2 billion won. Hyori has had a huge impact on the South Korean music industry with her brand of confident sex appeal and catchy music. For her undeniable contribution and for being a formidable force in the industry, she has been labeled a K-pop queen.

The two most important factors that have propelled her transition—her exit from Fin.K.L. and exerting control over her image—showed that she took ownership of her career. She partakes in lyric composition occasionally, but she is not the mastermind behind its content, production, or arrangement, so she is not regarded as an artist in the creative sense. However, because she owns and sells her sexy image so convincingly as a performing artist and her influence in K-pop is so pervasive, people no longer classify her as an idol. They may refer to her as a former member of Fin.K.L., but her own legacy and influence has superseded or is at least on par with her former group’s.

Another factor that cemented her transition is age. Hyori is over 30 and most singers lose the idol label once they reach the 30 plus mark, especially if combined with the aforementioned factors. It is important to note that Hyori developed into a successful soloist while she was still in her 20s, but there was a big difference between her and other idols who were her age at the time—idols her age were mostly targeted towards a younger audience, but Hyori being a solo artist attracted a wider audience because of her image. Image is a huge part of what gives the “artist” label its prestige. The public and the Korean internet community have a history of castigating idols who tackle mature concepts or display a provocative image. Soloists, however, have less controversy selling sex appeal because they have an older audience and have more control over their image, so they can have a risqué and mature concept with less criticism directed towards them.

Hyori’s largest artistic setback is the plagiarism scandal that almost derailed her career. In April 2010, she released her 4th album “H-Logic.” Korean internet users soon started to make allegations that 7 of the 14 songs on the album written by up and coming composer Bahnus, were plagiarized. Hyori was forced to suspend all of her activities following the backlash and Mnet Media, Hyori’s agency, sued Bahnus for theft and deception. He was sentenced to a year and six months and ordered to pay a hefty fine. The scandal happened almost 3 years ago, but Hyori is just getting ready to return to the music industry with a new album this May. While most people would still consider Hyori a good performing artist and most acknowledge that she was never known as the creative force behind her music, her artistic integrity has still been jeopardized because of the controversy. Hyori’s scandal proves that in the quest to attain real artistry, an idol must remember that a true artist can try to be innovative, but he or she must always be honest. Nobody respects an artist without integrity because no one likes a fraud.

Many of today’s 2nd and 3rd generation idols are following examples set by Hyori and other 1st generation idols. Idols are blossoming into respected soloists—exercising more control over their image and music. G-Dragon is a respected idol because he treads the line between both labels. He produces, composes, and has some control over his image, but he is a member of idol group Big Bang. Big Bang is one of the few K-pop groups that have had a strong cultural impact on South Korea with their image and music. G-Dragon has played a sizable role in making Big Bang a huge success with his fashion forward image and penning most of their career defining hits. Starting with the composition of their breakout hit single “Lies,” his artistic input from the onset of Big Bang’s career made him standout. He has also been instrumental in laying the foundation for his own successful solo efforts, as well as collaborating with his bandmates and other YG Entertainment artists on their solo albums. It is too early to assume at this stage of his career he’ll be able to completely dissolve the idol label still associated with his moniker– but because he is such a vital asset to Big Bang’s artistry and image, he is probably more respected than any other idol when it comes to crossing the artist threshold.

Unfortunately, like Hyori, GD has encountered his fair share of setbacks with plagiarism controversy. In 2009, after the release of his first solo studio album “Heartbreaker” Sony Music complained to YG Entertainment that G-Dragon’s “Heartbreaker” was too similar to American rapper Flo-Rida‘s “Right ‘Round.” YG and Sony Music scuffled back and forth until YG contacted Flo-Rida and the two collaborated on a new version of the song together. G-Dragon has stated that the plagiarism scandal affected him in many ways, but he has bounced back resiliently, continuing to write and produce music after overcoming public humiliation and backlash.

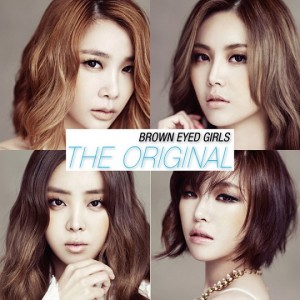

Age and image maturation is also a huge factor in how current idol groups and artists are labeled. Brown Eyed Girls treads the line between an idol group and artist because they tackle adult themes, play a role in producing and composing their music, have a mature image, and 3 out of 4 of their members are over 30. It has garnered them the “adult idols” moniker, especially their resident sex kitten, Narsha, the original “adult-idol.” Their embodiment as strong sexy women is as distinctive as their age and how the public perceives their representation of maturity.

Older idol groups like H.O.T and g.o.d have former members regarded as artists because their groups have disbanded and they’ve become too old to be labeled idols. Singers like Kim Tae-woo from million seller idol group g.o.d (1999-2006) have gotten married, had a child, and focus on solo activities. Kangta from 1st generation idol group H.O.T (1996-2001) is an executive at S.M. Entertainment, who plays an important role molding the company’s new generation of idols. Older idols who undergo an image change, may also switch music genres–transitioning from pop-oriented, upbeat dance music to songs that showcase their talent and growth, such as ballads, OSTs, or pop songs with adult themes.

One of the complications of converting the “idol” label to “artist” is how accurately each term defines what the job entails. The word “artist” only describes a fraction of what an idol’s career consists of—singing, dancing, and maybe acting. There isn’t another word that people use as an umbrella term to denote that in addition to music and acting, idols perform hosting, commercial modeling, variety show appearances, and dabbling in numerous other show business activities. Contrarily in the West, singers could do all these things and still be labeled artists because that is their main profession. While it is my personal belief that idols are mainly singers, a sizable part of their career and income stems from doing several different jobs as “idols.”

Many fans are probably wondering why idols want to be labeled as artists now, when the word has been a part of the K-pop lexicon for over 20 years. The idol surge of the past few years have led to the term “idol” taking on a negative connotation because increasing number of idol groups over-saturated the market. Being an idol still has its flashiness, but it’s not associated with creativity, authenticity, and the mature appeal of an “artist.” More than ever before, they are getting frustrated by insults criticizing their lack of vocal talent, performance skills, creativity, and their manufactured image. Some have voiced their desires to be seen as artists because many of them contribute more than just a performance aspect to their group. Idol-artists, a term I’ve dubbed for them, want to avoid being groups with other idols who have no artistic merit, image ownership, or performance prowess.

The word “artist” indicates a creative input lacked by idols. It is a more prestigious marker because it indicates music and image ownership. The desire to become an artist is an important career aspiration because the typical idol career is short. However, becoming a soloist is a natural progression because idol groups disband by the time members reach 30, so members transition to solo projects to remain relevant in the entertainment industry. If an idol wants to be labeled an artist while still in an idol group, it can be extremely difficult because the “artist” distinction may only be suitable for one or two persons in the group, and not all the members. Despite the criticism, more idols are being recognized for their artistic contributions to their groups, other groups, and soloists. The members of JYJ, JeA and Miryo from Brown Eyed Girls, as well as Zico from Block B are a few idol-artists, who challenge the notion that idols can’t be artists or developing artists—as they continue composing, producing, and arranging music, instrumental in their pursuit of artistic recognition.

There is no clear cut route for how an idol can transition to an artist. It has happened before and it will continue to happen as more idols play apart in the creation and execution of their image and music. Being regarded as an artist is something that takes time, but it is important to note that the term “artist” is not a static one. Music artists can be performers who exert influence over their image, but have songwriters, producers, stylists, and image consultants that polish them into artist ready perfection. This is how many “artists” in the West (and the East) operate behind-the-scenes. “Artists” like these aren’t considered artists in the innovative sense of the word, but rather “performing artists” because their artistic expression is based more on their output, rather than their musical input. There are different ways to move from idol to artist and it is an important transition to make because to idol-artists and even regular idols, it comes with the prestige, respect, and maturity they want to attain.

(images via SM Entertainment, B2M Entertainment, YG Entertainment, TS Entertainment)