For Korean drama in 2021, cults, violence, and the mixing of the two are a hot topic. From the grotesquery of the monsters in Netflix’s own Sweet Home and Kingdom, to Squid Game’s twisted brutality, and TvN’s religious zealots overseeing violent ends in Dark Hole and Hometown, these themes have been particularly popular this year. Given the, well, extreme ideologies cults lean towards, and their frequent entanglement with mysticism, it was inevitable that dramas would soon leap at the chance to combine them completely with the supernatural and the bloody.

Hellbound, from zombie masterpiece Train to Busan director Yeon Sang-ho, is Netflix taking this chance. Based on a webtoon of his own creation, the series boasts names as big as Yoo Ah-in and Kim Hyun-joo, in a world where avenging CGI ‘angels’ appear to certain individuals, whose death has been foretold, to take them to Hell. And boy, they do not take them gently. Weaving in an increasingly terrifying cult and their vigilantes, Hellbound is a story that questions the nature of justice, hysteria, groupthink, and the uncomfortable intersections of these ideas.

This review contains spoilers.

With an evocative name like Hellbound, there is an instant association with horror only furthered by the director’s most famous work. And yes, in essence, the core of this story is horrifying, at least in its concepts and incorporation of the supernatural. This program is set literally one year ahead from now (the opening scene is very pointedly set on November 10th, 2022 at 1:20pm), in a world where certain individuals receive terrifying prophecies from ‘angels’, giving the exact time and date they will be ‘taken to Hell’. The show’s opening scene demonstrates exactly what this means, when a man in a coffee shop is suddenly pursued by three huge, hulking figures, seemingly made of stone, who chase, beat, and ultimately burn said man to a crisp via a ball of light.

Why did this man meet this particular fate? Well, the main answer given in this world comes from the sinister New Truth cult, and their answer is simple: he was a sinner. This cult is led by Yoo Ah-in, hailed as a prophet who recognises these ‘demonstrations’ as evidence of God’s punishments for humanity’s sins. So far, so spooky. This set-up is given to the audience within the opening half of the first episode, setting up these key ideas of divine justice and retribution right from the off. The swiftness with which these ideas are established is efficient, enabling the ideas and set pieces time to unfurl as fully as possible over the series’ six episodes.

As well as the thematic set-up being quick, we are introduced, at least seemingly, to our core cast and core tone extremely effectively, with a tightness mirroring that in Train to Busan. There is weathered detective Jin Kyung-hun (Yang Ik-june) with a murdered wife (at this point I think that’s a job requirement for this particular profession), upstanding lawyer Min Hye-jin (Kim Hyun-joo) and an assortment of beleaguered cops and disturbing cult members to take in. The show works well to give us the glimpses of emotional complexity that create depth and investment, such as the flashback to Kyung-hun attending his murdered wife’s crime scene and breaking down. With a run time this short, these moments become all the more key, and they are not lost.

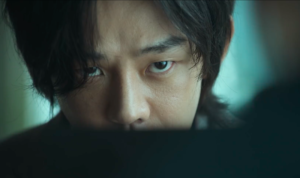

It’s worth giving particular praise to Yoo Ah-in’s performance as Chairman Jung Jin-soo in this regard. As the seemingly benign and gentle leader of a sinister new Christian ideology, Ah-in works well to convey this at the surface level, while giving just enough hints that something more sinister is underneath. This level of control comes through the mastering of the blank-yet-not-emotionless face, something that lesser dramas fail at, leaving us with bland rather than menacing.

His emotional complexity reaches its peak in episode three, an episode in which he both admits to murder to Kyung-hun, explains his own poignant upbringing and how it led him to his position in the present. Both Ah-in’s performance and the show’s writing never let this fall entirely into the pitiful or fully evil camp, and the character is all the more compelling for it.

This balancing between understandable motivation and the fall into full malevolence is itself a key theme that develops across the show. There is certainly a clunkiness to this development, as the show jumps forward three years after the end of episode three. It feels as though this is intended to demonstrate the starkness of the change in perceptions around what these bizarre events mean, and it does to an extent. It would, however, have been nice to see the encroachment of these viewpoints a little more gradually, if timing had allowed.

The difference in these perceptions is in their interpretations as just events. When they begin at the start of the show, the ferocity and inevitability of these creatures appearing and burning their victims to cinders stokes an obvious fear, confusion and panic. However, through Jin-soo’s words and the followers surrounding him, these events soon come to represent retribution finally being unleashed on the sinners of the world.

The problem that emerges in the later half of the series is: what exactly are the sins these people committed, and do they really deserve this fate? As the grip of New Truth becomes more powerful and all-encompassing on society, this question becomes the core of the show. With seemingly more and more people being selected for this fate, with increasingly small motivations, Hellbound turns its focus to the nature of justice, asking who defines it, and what role others play in it.

Exploring this via a cult that has no problems employing the services of ruthless vigilantes raises important questions about the motivations of these kinds of groups, encapsulated in wonderfully small details. In one delicate example, the new chairman of the cult politely asks a broadcaster what the ratings percentage of a ‘demonstration’ broadcast on live TV is. The supernatural justice of this world becomes slowly exposed as a tool for the power-hungry to achieve their goals, with the fantastical elements not being the true source of evil at all.

It is a good thing the story is able to unfold these ideas so well itself, as Hellbound’s biggest weakness is in its use of CGI effects to create its monsters. This problem emerges in part due to the translation that this medium went through, from its original form as a webtoon into a big budget streaming production. In the 2D world of illustration it is easier to blend the style of the monsters into the existing backdrop, whereas in live action, there will always be some kind of a loss of veracity. Unfortunately, in this case, it is in the decision to make the monsters seem almost made of rock, complete with the lumpiness, bulk, and lack of expression that entails.

Much like so many of the greatest live-action monsters, they are far more threatening before they appear, starting as booms and thunderous rumbles in the distance. The decision to make them bulky rather than, for example, spindly or serpentine, stops them from being as frightening as the scenario that they present.

This is made up for in part by the brutality of the violence we see inflicted on the victims. Whilst the monsters we see are so clearly from a computer, the blood, crunch and splat of the bodies they take is far more effectively rendered. As is the aftermath of each ‘demonstration’, where all that remains is a horrifically charred half skeleton. These moments are all the more horrifying because they are presented in so much more realistic way than giant rock creatures.

The sense of harkening to reality is also echoed through the cinematography. Whilst generally hitting the rich, filmic tone that one has come to expect from Netflix productions (and, of course, a film director), the more interesting moments came in the choice to briefly switch to point-of-view. Whilst this approach can sometimes seem low cinema, it worked well here, used in moments of high action and tension, to almost literally increase the viewer’s heartbeat. In combination with scenes presented as though we are watching livestreams or adverts on a screen, these choices from cinematographer Byun Bong-sun put the audience very directly in the action that we are watching.

In a show that concerns itself with how the group interprets justice in contrast to the individual, this move is especially pertinent. As the New Truth cult of this world increasingly forces a nonsensical yet dogmatic view on Hellbound’s world, these camera angles subtly remind us of the importance of individual interpretation and thought. As the victims of the demonstrations increase across the series’ run (and, very significantly, not always with sin to their name), we remember to keep our minds open to what it could all mean, and not to fall into the groupthink traps of the cult leaders.

These intriguing questions around justice and retribution do not get answered in Hellbound, mostly in a very deliberate way. The final scenes of the last episode strongly hint at a second series, so, as yet, this open-endedness is not a fault. The construction of the central conceit (CGI aside), the solid character set-up and confident narrative structure allow enough enjoyment in pondering these questions for the time being. This universe where Hell pops up to visit Earth, with a God different in everyone’s eyes, is so far an intriguing one. If Yeon Sang-ho can expand and develop it further in the same way, then Hell on Earth could end up being a pretty exciting prospect.

Images via Netflix.