Note: this article discusses sensitive topics such as mental health and suicide. Please read with caution.

Earlier in October two idols announced that they would be halting activities due to mental health issues. Both Nam Taehyun and Soyul from WINNER and Crayon Pop, respectively, have halted work with their groups in order to focus on improving their mental health. Both announced they are suffering from an anxiety disorder, which is the most commonly diagnosed mental illness in the United States according to the National Institute of Mental Health.

Earlier in October two idols announced that they would be halting activities due to mental health issues. Both Nam Taehyun and Soyul from WINNER and Crayon Pop, respectively, have halted work with their groups in order to focus on improving their mental health. Both announced they are suffering from an anxiety disorder, which is the most commonly diagnosed mental illness in the United States according to the National Institute of Mental Health.

This isn’t the first time — and unfortunately probably won’t be the last time — idols will need to stop working in order to take care of their mental health. However, it feels like it’s become more common for these events to occur.

Mental illness is defined by the Mayo Clinic as:

a wide range of mental health conditions–disorders that affect your mood, thinking and behavior. Examples of mental illness include depression, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, eating disorders and addictive behaviors.

Many people have mental health concerns from time to time. But a mental health concern becomes a mental illness when ongoing signs and symptoms cause frequent stress and affect your ability to function.

It’s a broad term and, as stated, it is common for people to experience it from time to time. That said, the frequency that it seems idols have to take breaks because of their mental health is more than a little concerning. The list of idols who have publicly admitted to suffering from some sort of mental illness is long and comprehensive. It spans from first generation idols like Junjin from Shinhwa, to second generation idols like Heechul and Leetuek (Super Junior), G-Dragon and T.O.P from Big Bang.

It’s a broad term and, as stated, it is common for people to experience it from time to time. That said, the frequency that it seems idols have to take breaks because of their mental health is more than a little concerning. The list of idols who have publicly admitted to suffering from some sort of mental illness is long and comprehensive. It spans from first generation idols like Junjin from Shinhwa, to second generation idols like Heechul and Leetuek (Super Junior), G-Dragon and T.O.P from Big Bang.

Even newer idols have opened up about their struggles with mental illness: Suga went in depth about his struggle on his mixtape, and JinE from Oh My Girl recently had to stop promotions to receive treatment for an eating disorder. Just last year, trainee and idol hopeful Ahn Sojin committed suicide, apparently in part because she did not make it into KARA, and her contract with DSP was terminated.

Being any kind of public figure is stressful enough as it is, but when you add the already harsh environment many K-pop idols face on a day to day basis, it is easy to see why some develop or show signs of mental illness. What is not okay is the apparent lack of support from the system that they have dedicated their lives to. It is difficult as an outsider to tell exactly what kind of support idols get to help ensure their mental health, but with how common mental illness has become in idols, one can assume it’s not enough.

Before we go any further, let me issue this disclaimer: I can only speak as an observer and an outsider to Korean society. I cannot pass judgement on how to change the system, only acknowledge that the system needs to change in some way. The status quo is not working and something needs to change.

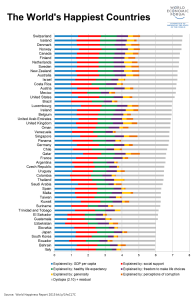

South Korea has had the highest rate of suicide among all developed countries for the past 10 years according to the OECD. This comes from a variety of factors, including playing catch-up with their welfare system and immense emphasis on material wealth; but one thing that seems to influence this most is the social stigma surrounding mental illness. There’s a stigma in most countries surrounding mental illness, but many studies and reports on the subject show that in many Asian countries this stigma is significantly higher than other countries.

South Korea has had the highest rate of suicide among all developed countries for the past 10 years according to the OECD. This comes from a variety of factors, including playing catch-up with their welfare system and immense emphasis on material wealth; but one thing that seems to influence this most is the social stigma surrounding mental illness. There’s a stigma in most countries surrounding mental illness, but many studies and reports on the subject show that in many Asian countries this stigma is significantly higher than other countries.

Frequently, those who are diagnosed with a mental illness face difficulty getting a job or even keeping their jobs. On top of these fears, the traditional “family first, individual second” society can sometimes make people feel like they need to push aside their individual needs in order to maintain the pride of their family. It’s also still very taboo to discuss feeling depressed, or anxious, even among friends and family members.

All these factors could influence why people internalize this stigma and don’t seek help. Studies on this topic have found that because of the stigma many people don’t trust Western-style psychiatrists or psychoanalysis and there is not as much of an emphasis on talk therapy. Many times patients are referred to inpatient treatment. Some even — when they do receive treatment — may not adhere to their treatment plan, thus inhibiting their recovery.

It’s important to understand what kind of environment idols are in to try and make sense of why it seems like more and more idols are being treated for mental illnesses. In a society where the negativity surrounding one’s mental health is so prevalent, you can’t blame people for wanting to keep quiet, to try and just get through it without asking for help. But with the pressure idols are under to be perfect, to always reach perfection, it really is not surprising that idols sometimes crack. They’re only human after all. It doesn’t make the silence okay or right, but it is an understandable response to their mental illness.

It’s important to understand what kind of environment idols are in to try and make sense of why it seems like more and more idols are being treated for mental illnesses. In a society where the negativity surrounding one’s mental health is so prevalent, you can’t blame people for wanting to keep quiet, to try and just get through it without asking for help. But with the pressure idols are under to be perfect, to always reach perfection, it really is not surprising that idols sometimes crack. They’re only human after all. It doesn’t make the silence okay or right, but it is an understandable response to their mental illness.

For some, the pressure is too much and they feel so helpless that they end their lives. Four popular idols have committed suicide over the years, with the most recent being the aforementioned Ahn So-jin and one of the older cases being U;Nee in 2007. While not nearly as many idols have committed suicide as actors, the fact there have been so many and this unfortunate trend shifting to idols is concerning.

However, there is also a positive shift. Yes, it feels like idols are constantly taking breaks because of one aspect of their health, but the fact that we are seeing more artists opening up about struggling with anxiety, depression, eating disorders and other mental illnesses signals a positive change. Suga’s whole mixtape references his past struggles with mental illness, as well as Rap Monster’s mixtape. Amber opened up about her experiences with depression and discrimination because of her looks in “Borders” and in subsequent interviews. Even worldwide stars Big Bang have opened up about struggling with depression during “Happy Together” in 2015. Back in 2013, a few high profile female idols discussed their own experiences: Sojung from Ladies’ Code opened up about her struggle with anorexia, Taeyeon and Suzy both alluded to dealing with depression.

Having these high profile idols speak out helps lessen the stigma and forces South Korea to grapple with its mental health issues. It also lets young people who might be going through the same thing know that they’re not alone; that someone else has struggled and made it through. A mental illness can affect anyone, no matter how rich or poor, even if they have everything in the world. It’s a good thing to have these idols be honest about their problems. It shows that, however slowly, it is becoming more and more acceptable to be open about these topics.

There’s no real right or wrong answer to this problem. The only thing that’s obvious is that there’s clearly a problem with how idols’ mental health is being handled. Only a few entertainment companies have openly talked about providing mental health checks and services. Until it’s more widespread and expected that companies provide these services, it’ll be difficult to ensure the health of idols and even trainees. Those who have spoken out publicly are helping normalize mental illness in the long run, but for now the ever present issue is still making it minimally acceptable for people to discuss their mental health.

There’s no real right or wrong answer to this problem. The only thing that’s obvious is that there’s clearly a problem with how idols’ mental health is being handled. Only a few entertainment companies have openly talked about providing mental health checks and services. Until it’s more widespread and expected that companies provide these services, it’ll be difficult to ensure the health of idols and even trainees. Those who have spoken out publicly are helping normalize mental illness in the long run, but for now the ever present issue is still making it minimally acceptable for people to discuss their mental health.

The culture and stigma surrounding mental illness needs to be addressed and companies should perhaps consider providing better support. Fans can send messages of support and respect the idols’ privacy. But what’s needed most for anyone who is suffering is compassion from the society they live in. Once steps are taken in a more compassionate and understanding direction for those who have a mental illness, maybe less people will feel the need to hide their struggles and we will see less idols suffering from mental illness to the point they can’t do what they love.

(Sources: Critical KPOP, Mayo Clinic, NIMH, OECD, The Hankyoreh, “Internalized stigma and its psychosocial correlates in Korean patients with serious mental illness,” Woo, Youn, et. al, New York Times)