Last month, CL did an interview with Paper Magazine where she and Jeremy Scott discussed a variety of topics including pop culture, K-pop and Asian girls. The interview was fairly standard until the last paragraph where CL calls out Asian girls as basic.

Last month, CL did an interview with Paper Magazine where she and Jeremy Scott discussed a variety of topics including pop culture, K-pop and Asian girls. The interview was fairly standard until the last paragraph where CL calls out Asian girls as basic.

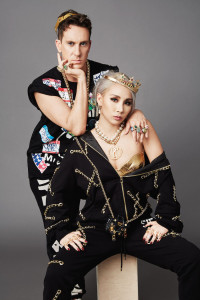

To give some background on the Paper Magazine interview, it read as primarily concerned with giving detail on CL and Jeremy Scott’s relationship. The pair go over how they became socialite friends and surprise partners in a stage performance. The rapport, beyond simply designer and artist, is illustrated through their anecdotes of their first interactions.

The interview goes into more details regarding style, since CL and Jeremy Scott’s ties intersected when she adopted his fashion from the start of her career. It is something that CL’s group 2NE1 has built upon — an image of eccentricity that not only runs through their music but also through their dress. In K-pop, elaborate costumes often define periods of an artist’s career as much as a song does.

2NE1’s CL came at a time when being a female idol rapper in Korea was not synonymous with being a good rapper. She and 2NE1 faced a lot of hurdles during debut — especially going against the types of femininity that are usually looked positively upon. They played against those typical forms with their streetwear dress, display of ownership over their feminine sexuality, strong charisma as female performers and unashamed claim to power as women who didn’t feel the need to follow the traditional ideals of what is considered feminine.

While her story in Korea is complex, her expansion into the Western market comes with a different type of culture that understands Asian stories differently. Her statements can be especially apprehensive when she expands simplistic terms to comprise of women in all of Asia.

Though CL does hold responsibility for her cavalier statements, there also exists a responsibility in the audience for understanding that one person does not represent the whole. From the perspective of an Asian American, her statements are disparaging. (Note: her statements can also be examined from the perspective of an Asian woman, for whom CL’s statements may have a different weight culturally and historically.)

It is important to not be dismissive of CL’s voice at the start. CL likely had honest intentions of implying that she wanted to be a positive role model to girls and show them that it is okay to be different. Where her message gets lobbed into the wind and susceptible to criticism is when she says:

It is important to not be dismissive of CL’s voice at the start. CL likely had honest intentions of implying that she wanted to be a positive role model to girls and show them that it is okay to be different. Where her message gets lobbed into the wind and susceptible to criticism is when she says:

“A lot of Asian girls love being basic because it’s safe.”

She continues with:

“Girls in Asia are very obedient, shy, timid, quiet…”

It’s fairly easy to see how many people would take umbrage with CL’s statement. She paints Asian women as not much more than a stereotype. CL wants to separate herself from this typification, and she uses the term ‘basic’ to relegate Asian females as ‘timid’ and ‘shy.’ The problem is that CL, as a figure on a public platform, is assumed as an expert representative who speaks on behalf of all Asian women. To speak on behalf of one ethnic group alone would be a tough task as there are a lot of sides to consider including cultural notions of respectability, historical hierarchies and modern feminist movements in Asia.

By couching Asian women into a limiting stereotype, thereby reaffirming preconceived notions of this complicated racial grouping, she finds herself in a spot of trouble. Were she to acknowledge that a culture of this ‘basic’ style exists is one matter, but to play to these preconceptions of the Asian woman and positioning herself as the harbinger of change ignores and almost subtly invalidates other voices. It isn’t just a basic issue, but one of more cultural complication. Instead of pigeonholing Asian women in these traditional stereotypes, CL probably could benefit from attacking mainstream representations of the Asian woman.

However, to be completely dismissive of CL’s statements is to not acknowledge that in Paper Magazine, she is speaking to an audience as a minority. In Negotiating Power From The Margins, Manju Kurian suggests:

“Women of color use various autobiographical forms to negotiate what power they have from the margins at which they are placed.”

In the US, CL would be categorized as a minority, whose story is at odds with representing all of a culture. Kurian quotes Gayatri Spivak when she goes on to relay how minorities face an odd catch 22 when discussing their culture.

“(We) have to be careful to not become ‘native informants’ of our cultures, the singular representatives for lands riddled and enriched with difference(s). If we do not define ourselves, then we are defined, labeled, and categorized.”

For CL to not be able to speak of her culture opens up her story to being susceptible to preconceptions of her race, and for her to speak up relegates her to the pitfalls of being a singular representative for a very diverse and large population of people. As an Asian and a female trying to make it in the Western market, she occupies this space where she is expected to speak for Asians because of the limited visibility of Asians in popular media. CL holds this burden of representation on her shoulders because regardless of what she says, she represents all Asians — especially as someone with a larger public profile.

CL needs to be careful to not give creed to media stereotypes and instead realize that she is at the intersection of various cultures. She hails from Korea and the K-pop sphere while also occupying a role as an Asian in the Western market. Her style and music also involves a lot of aesthetic borrowed from hip hop culture. She has a lot to learn of the histories of all these different representative groups that she belongs to in the US. Whether she speaks about it or not, her words as a member in these groups and as someone of an elevated public profile should be conscious of the broader reach and societal issues that exist.

CL needs to be careful to not give creed to media stereotypes and instead realize that she is at the intersection of various cultures. She hails from Korea and the K-pop sphere while also occupying a role as an Asian in the Western market. Her style and music also involves a lot of aesthetic borrowed from hip hop culture. She has a lot to learn of the histories of all these different representative groups that she belongs to in the US. Whether she speaks about it or not, her words as a member in these groups and as someone of an elevated public profile should be conscious of the broader reach and societal issues that exist.

Should CL have been more wary of categorizing Asian women as ‘basic’? Sure, but this situation has opened up an opportunity to discuss the role of race and gender, especially when left to stereotypes, in determining acceptance into national identity and how belonging to these categories can incur questioning and function as social barring from citizenship.

Women of color have historically been shut out of gaining the same rights as other citizens even as they are called upon to answer for their race and ethnicity as experts simply because they belong to that categorical group. Even as CL tries to distance herself from these stereotypes, it does not stop race from affecting how she is received in the US. Even as someone that can speak English, she’s always going to come under fire for her racial background — something that wouldn’t necessarily happen to foreigners of the US market that are white, like Justin Bieber or One Direction.

It becomes easy for us to forget how historical representations of Asian women have placed CL in a tricky spot. With it comes an unfair weight to shoulder how Asian women are perceived. The burden to represent Asian women against the stereotype. The burden of being accepted by US media. The burden of trying to represent herself.

We need to realize that a person can belong to a race and ethnic group but still not be representative of all peoples in those groups. CL is not an expert of all things relating to Asian women and maybe when popular media stops expecting her to be so, her statements will not feel the need to embody such broad categories of people.

(Papermag, Kurian, Manju S. “Negotiating power from the margins: lessons from years of racial memory.” Women and Language 19.1 (1996): 27+, images via Papermag, Harper’s Bazaar, Twitter, and YouTube)