South Korea is a country full of seasonal traditions, and summer is no exception: Sambok is celebrated by eating samgyetang and other traditional dishes, misutgaru is plentiful, DEUX’s “In Summer” makes it’s way back to the airwaves, and of course, audiences flock to the cinema to have their wits scared out of them with the latest horror flicks.

South Korea is a country full of seasonal traditions, and summer is no exception: Sambok is celebrated by eating samgyetang and other traditional dishes, misutgaru is plentiful, DEUX’s “In Summer” makes it’s way back to the airwaves, and of course, audiences flock to the cinema to have their wits scared out of them with the latest horror flicks.

While many in the West celebrate the horrors of Halloween in October, South Korea has a strong horror film trend in the summer. Why? Because there’s nothing like a chillingly creepy film to cool you down in the summer heat. Even Shinee’s recent Married to the Music MV used the campy tropes of the horror genre — though in a slightly less scary way — to entertain audiences just this past month. It seems in the dog days of summer, there’s no better way to cool down than to break out in a cold sweat, and many idols and film production companies rise to the occasion every year.

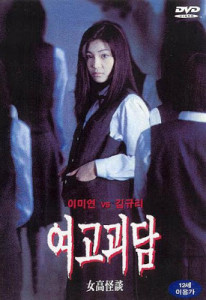

Keeping in mind that South Korea has a smaller film industry than many other countries, it’s not like horror films come out in droves during the summer season. However, every year a couple new films make their way to theaters to induce chills in moviegoers. Most of South Korea’s “classic” horror films were released during the dog days of summer, including the classics Whispering Corridors, A Tale of Two Sisters, The Host and The Red Shoes. This year, the films The Piper, The Chosen: Forbidden Cave, and The Silenced hit theaters, in addition to several other horror film showings at the Bucheon Film Festival.

So now that we know the reason behind the trend, it seems seasonally appropriate to explore a bit of the history and tropes that make the Korean Horror Genre successful.

The (Quick) History of Korean Horror

Aside from being a method of fighting the summer heat, horror films have had a presence in Korean cinema dating back to the 1960s, when directors like Lee Yong-min and Kim Ki-duk first used elements of the supernatural and monsters to explore traditional lore and national anxieties on the screen. Unfortunately, as government censorship began to crack down more heavily on the film industry under the Park Chung-hee dictatorship, directors’ creativity was routinely restricted and censored.

Aside from being a method of fighting the summer heat, horror films have had a presence in Korean cinema dating back to the 1960s, when directors like Lee Yong-min and Kim Ki-duk first used elements of the supernatural and monsters to explore traditional lore and national anxieties on the screen. Unfortunately, as government censorship began to crack down more heavily on the film industry under the Park Chung-hee dictatorship, directors’ creativity was routinely restricted and censored.

However, during this time, directors like Kim Ki-young rose to prominence and (re-)popularized many of the horror tropes that are still prevalent in contemporary Korean Horror. Kim Ki-young worked under the guise of melodrama to craft some of the most influential South Korean horror films including The Housemaid (remade in 2010), Killer Butterfly and Iodo. All these films revolved around malevolent women and introduced camp and cult style cinema while serving as a somewhat well-received critique of society. South Korean horror also made it’s first international appearance at the Venice film festival in 1979 with Death Cottage.

Following the assassination of Park Chung-hee and Seoul Spring, the political turmoil of the 1980s caused a major lull in not only horror films, but Korean cinema in general. By 1980, the fictional horrors of the cinema began to “[pale] before [the] reality” the nation was experiencing. Genre films all but died out publicly and relocated to underground student movements (which was the catalyst for Independent Korean cinema).

It wasn’t until the 1990s when Korea’s film industry was re-invigorated. Not only was the country more politically stable, but for the first time, the film industry was booming with young, foreign educated directors who slowly revolutionized Korean cinema. In addition to the fresh blood, came the government’s delayed interest in exporting Korean cinema globally and the lifting of many censorship bans that had previously limited filmmakers.

It wasn’t until the 1990s when Korea’s film industry was re-invigorated. Not only was the country more politically stable, but for the first time, the film industry was booming with young, foreign educated directors who slowly revolutionized Korean cinema. In addition to the fresh blood, came the government’s delayed interest in exporting Korean cinema globally and the lifting of many censorship bans that had previously limited filmmakers.

The Korean Blockbuster

It’s no surprise that Korea, with its much smaller film industry, had been importing blockbusters for decades by the time the cinema boom of the 1990s took place. With the revival of the film industry in the early 1990s came the increase of corporate and government interest and investment in the industry. Korean cinema had the potential to be a source of national pride — and a lucrative cultural export — if Korean production companies could compete with the imported blockbusters of Hollywood.

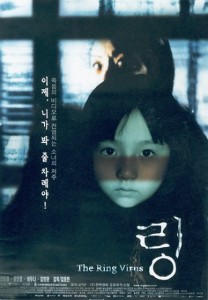

And although Japan also had a thriving horror industry in the late 1990s that a few Korean remakes were born of — and the two genres share many tropes — up until 2004, Japanese films were only allowed to show in South Korea if they had received some kind of award previously. This means that Korean audiences encountered the Korean the Ring Virus six months before the Japanese original, Ringu, made it’s way to cinema screens.

And although Japan also had a thriving horror industry in the late 1990s that a few Korean remakes were born of — and the two genres share many tropes — up until 2004, Japanese films were only allowed to show in South Korea if they had received some kind of award previously. This means that Korean audiences encountered the Korean the Ring Virus six months before the Japanese original, Ringu, made it’s way to cinema screens.

With a little financial push — and the pressures of globalization — Korean cinema began to shift away from imported blockbusters, and instead focused on the creation of South Korea’s own blockbuster film industry. Alongside the increased investment in film production came the first Cineplex in the late 1990s, and audience draws were increasing exponentially with the growing amount of screens available in the country.

With increased investment also came increased production costs, which was bad news for independent and small production companies. It became ever more difficult for production companies to compete with the growing blockbuster trend. Horror genre films became the answer for smaller studios like Cine 2000 to produce cheaply made films that could still draw and audience. The film Whispering Corridors, produced by Cine 2000, became the cheaply made horror film that would re-invigorate the genre and kick off the wave of Korean horror that audiences world-wide are now familiar with.

Korean Horror Tropes: Folklore and Femininity

The use of females — and their sexuality — has been at the cornerstone of Korean horror for decades. One of the very first Korean films, Ch’unhyang-jon, revolves around a wife who is all but tortured in an attempt to stay loyal to her absentee husband. At the time, in the wake of the Korean War, many Koreans identified with such motifs and the film was “likened by some to a symbolic retelling of divided Korea and its rape by foreign powers.” The female trope also carried on through all of Kim Ki-young’s films, but in that time the young woman shifted from the heroine to the villain.

Korean horror stories — whether they be monster flicks like The Host and Thirst or ghost stories like Whispering Corridors — often also take from traditional folklore and combine a bit of the everyday to tap into the anxiety of audiences (and provide a little critique while they’re at it). It makes sense that Korean horror relies less on blood and gore and leans more towards psychological horror, given the years of censorship that shaped the genre — but who said everyday life couldn’t be terrifying? As one of the characters in Whispering Corridors states, “School can be a horrific experience for both students and teachers.”

Korean horror stories — whether they be monster flicks like The Host and Thirst or ghost stories like Whispering Corridors — often also take from traditional folklore and combine a bit of the everyday to tap into the anxiety of audiences (and provide a little critique while they’re at it). It makes sense that Korean horror relies less on blood and gore and leans more towards psychological horror, given the years of censorship that shaped the genre — but who said everyday life couldn’t be terrifying? As one of the characters in Whispering Corridors states, “School can be a horrific experience for both students and teachers.”

Both Whispering Corridors and it’s groundbreaking follow-up Memento Mori took place in all-girls high schools and centered around the relationship between female students. Whispering Corridors played on the traditional Korean of genre kuel-dam, in which the spirit of someone who died a particularly violent death is trapped on earth and unable to pass into the afterlife. But, Whispering Corridors updated the tale with a “thoroughly contemporary setting” and modernized concerns — like the authoritarian school system and evil teachers.

The success of Whispering Corridors also hints at a prominent trend of contemporary and traditional Korean horror: most of the stories revolve around young women. These stories also draw from Korean folk lore: the wronged virgin ghost (gwishin), the nine-tailed fox (gumiho). One has to look no further than the numerous movie posters to see that Korea’s horror cinema is fascinated with femininity, in both its innocence and its benevolence.

The success of Whispering Corridors also hints at a prominent trend of contemporary and traditional Korean horror: most of the stories revolve around young women. These stories also draw from Korean folk lore: the wronged virgin ghost (gwishin), the nine-tailed fox (gumiho). One has to look no further than the numerous movie posters to see that Korea’s horror cinema is fascinated with femininity, in both its innocence and its benevolence.

With the resurgence of the Korean horror genre in the late ’90s and early 2000s came the prominence of not only the female ghost, but specifically the young girl as companies focused their marketing efforts on the teen demographic.

The commercial success of the recent Korean horror cycle demonstrates the case of a niche marketing strategy adopted by the Korean film industry. More importantly, the attempts by the makers of these films to appeal to adolescents and portray their social circumstances not only bring to the fore the consequences of the Korean education system but also seemingly authorize a culture of adolescent sensibility. (Choi, 2009).

Late ’90s and early 2000s horror flicks were successful with teen audiences because they combined the traditional fixation on the female, added the anxieties of modern life, and gave the teenage characters some sense of vindicated agency. This is what Jinhee Choi refers to as a “seonyeo sensibility” that is able to tap into the “emotional predilection, psychological dispositions and behavioral tendencies” that are oftentimes associated with the young female demographic.

Of course, to say that the Korean horror genre centers solely around females would be a lie; especially if films like The Host, Oldboy and I Saw the Devil are any indication. Nor are women in horror films exclusive to South Korea (the “Final Girl” seems to be a world-wide phenomenon.) But, the use of female characters in both South Korean folklore and cinema is unique in that, while the women are victims of terror, it’s oftentimes another women or simply circumstances that antagonize them — not some crazy man with a phallic chainsaw.

Of course, to say that the Korean horror genre centers solely around females would be a lie; especially if films like The Host, Oldboy and I Saw the Devil are any indication. Nor are women in horror films exclusive to South Korea (the “Final Girl” seems to be a world-wide phenomenon.) But, the use of female characters in both South Korean folklore and cinema is unique in that, while the women are victims of terror, it’s oftentimes another women or simply circumstances that antagonize them — not some crazy man with a phallic chainsaw.

In the years following the horror genre boom of the late ’90s, South Korean horror continues to impress and push the boundaries of traditional horror cinema. What began as a campy low-budget genre transitioned into a genre that is able to not only combine tradition and contemporary stress — but appeal to audiences world-wide. In South Korea, however, horror films remain the go-to summer cool-down tradition. It’s not just the theatre’s ridiculously high powered air conditioning that’s causing Korean audiences to break out in a cold sweat each summer, after all.

Readers, what Korean horror flicks keep you chilly in the summer? What’s your favorite Korean horror film?

(KoreanFilm, Korea Herald, KorMore, Gordsellar. Art Black, ‘Coming of Age: the South Korean Horror Film’, in Steven Jay Schneider, ed., Fear Without Frontiers: Horror Cinema Across the Globe (Godalming: FAB Press, 2003), pages 185-203. Peirse, Alison. Korean Horror Cinema. Edinburgh University Press, 2013. Byrne, James. Jinhee, Choi. “A Cinema of Girlhood: Sonyeo Sensibility and the Decorative Impulse of Korean Horror Cinema.” In Horror to The Extreme: Changing Boundaries in Asian Cinema, 39-56. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2009. Howard, Chris. “Contemporary South Korean Cinema: ‘National Conjunction’ and ‘Diversity'” In East Asian Cinemas: Exploring Transnational Connections on Film, edited by Leon Hunt, 88-102. New York: I.B. Tauris & Co, 2008. Images via: The Criterion Collection, Cine 2000, B.O.M. Film Productions Co., Mirovision.)