If you’re on TikTok (as many of us are), you’d realise that it’s almost impossible to escape music. Regardless of the type of content you consume on on TikTok, TikTok creators rely heavily on music of all genres to generate videos of less than a minute.

Other than trending music — both new and old — TikTok is a heaven for music discovery. With a catchy riff or a segment of relatable lyrics, small artists can rise to fame overnight. Global pandemic-induced lockdowns have only aided this process, as more users turn to TikTok to entertain themselves. Take Avenue Beat’s “F2020” or Em Beihold’s “Groundhog Day” as examples. These artists started out by simply sharing informal clips of their songs on TikTok, and the clicks generated on their TikTok videos eventually led to them producing official MVs and uploading them on formal streaming channels. It also helps that the global audience yields to shared experiences globally, even if to different extents, and tracks sharing similar sentiments to one’s own will undeniably be popular.

The same is happening for K-pop. It’s difficult to ignore the influence that K-pop songs have on TikTok trends. TXT’s “Anti-Romantic” steadily increased in stream count on TikTok and music streaming platforms after content creator Zuki uploaded a simple but addictive choreography to the b-side track. Without any promotions by TXT themselves, this electronic pop track has become one of TXT’s most streamed songs on TikTok, Apple Music, iTunes, and Spotify.

When “Anti-romantic”’s trend evolved from a dance to other avenues — such as song covers, and background tracks for romantic anecdotes — it got even the members of TXT themselves jumping on the trend. Like the aforementioned tracks, the relatability of the English-led chorus (“Sorry, I’m an anti-romantic”) makes it more receptible to a larger audience. “Anti-romantic” is not the only popular song on the platform; Zico’s “Any Song”, Black Pink’s “How You Like That”, Hwasa’s “Maria”, and a plethora of others come to mind.

The internet is full of think-pieces of how TikTok is changing the music industry. Artists are releasing single after single in hopes that a particular riff becomes viral. Songs are shorter, and pop music has started sounding more and more similar. When the algorithm recognises a certain element, it will undoubtedly push out similar sounding songs; in a demand-led music industry reliant on social media, this inevitably leads to little variation in title singles. Mainstream songs have already been getting shorter in the streaming age, and TikTok’s tendency for short videos doesn’t help this.

Largely though, K-pop has been immune to these TikTok-led industry changes. It’s more accurate to say that K-pop’s overall sound was already adept for TikTok creators to lean towards catchy verses and fast-paced beats. Block B’s “NalinA”, released in 2012, went viral on TikTok because it had an instrumental beat that was perfect for quick, short cuts that many TikTok creators need. “After School” by Weeekly features a chorus with upbeat instrumentals that makes it apt for light-hearted TikToks.

Whereas many Western artists are curating their songs to be the next viral hit, mainstream K-pop has often been produced with the idea of exportability since its beginning. For K-pop fans, TikTok is the perfect platform to make their favourite song the next viral hit.

That’s not to say that K-pop hasn’t lost out in one way or another. While K-pop is used as instrumental music for many videos, it is also promoted via dance challenges. Wanting to capitalise on this, many companies have simplified choreographies to ensure that they can be copied by the average individual — all for a dance challenge on TikTok to be successful. After all, even if K-pop is composed with a structure apt for TikTok, it wouldn’t hurt to make it even more adaptable for reception, right? (Well, it does hurt. Please let complex choreographies be the norm again.)

More than that, we have to remember that K-pop’s reception will not escape xenophobia. The idea of K-pop being too commercialised, impossible to understand (to a monolingual audience), or just “too Asian” hasn’t been defeated by its popularity on TikTok. Often times, the most “palatable” parts of the songs are taken, and then edited and shared so many times that there’s no way to tell these had Asian — let alone Korean — origins, as was the case in the above-mentioned “NalinA”, Red Velvet’s “Russian Roulette”, or APink‘s “Dumhdurum“.

With “NalinA”, what went viral was the instrumental beat, and it was used so much to the point that other than long-time K-pop fans, no one knew that the beat was produced by three artists sitting in a small studio in Seoul nearly a decade ago. What happens more blatantly is the removal of audio from popular K-pop choreographies and fitting them over English songs. There are many songs this has happened to, but “Russian Roulette” and Twice‘s “I Can’t Stop Me” are some of the more notable examples. “Russian Roulette”, in particular, went viral outside of Asia after dancers on TikTok copied the choreography and used it to dance to Migos’ “YRN”.

On one hand, the adaptability of K-pop elements can look like harmless fun. It’s easy to learn, easy to adjust, and easy to go viral, and people can do whatever they please with media they consume. On the other hand, however, seeing that K-pop has always been met with xenophobic sentiments and reviews by Western media, it’s difficult to see the adaptation of K-pop songs and dances — with no credit given — as simple fun. By removing the small element of credit, TikTok creators remove all roots of media to K-pop, sometimes even getting credited for dances and remixes by people who don’t know any better. With the additional fact that this often happens amongst non-Asian creators and consumers on TikTok, it’s challenging to see it as just harmless engagement.

That being said, it’s not all bad. A lot of K-pop’s marketability comes from the way idols interact with fans. Covid-19 lockdowns and pandemic restrictions have caused an even greater reliance on social media and technology to keep idols and fans connected. Fan meetings have turned to exclusive video-calls, instant messaging mobile applications have grown in popularity, and fancafe platforms have evolved to be more than simple messaging boards. TikTok’s quick, curated content thrives amongst this increased dependence on virtual communication.

Other than TXT, groups like NCT, Enhypen, Aespa, Loona, and many more have turned to TikTok as another platform to engage with fans, and it’s definitely more fun than the text-based communication that Twitter is used for or the image-driven communication on Instagram. On TikTok, these artists duet with fans, engage with viral memes, and participate in challenges that are started by themselves or by fans. Unlike other platforms, the chances of an idol stumbling upon a fan’s content is high, and this makes TikTok a much more exciting communicative channel than its social medium counterparts.

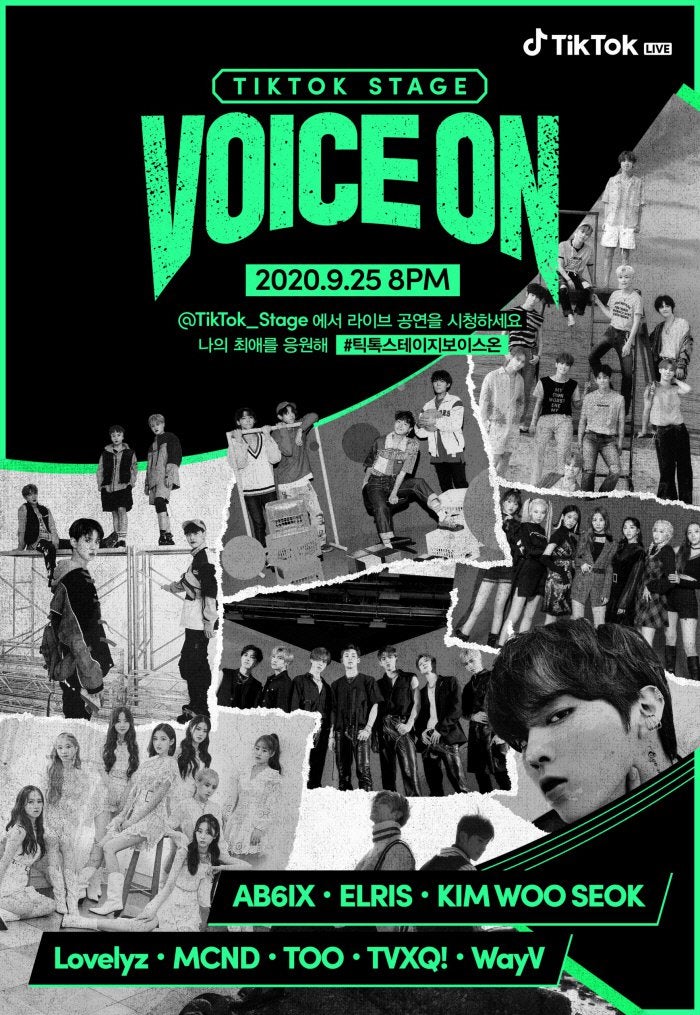

K-pop entertainment companies have recognised this, and have undoubtedly jumped on this chance to promote K-pop on such a large scale. TikTok Stage occasionally hosts K-pop concerts for free for anyone to attend by tuning in. Why free? Because TikTok ensures that the concerts are best viewed on the application itself — and that requires fans to sign up for the platform. If there’s anything TikTok can count on when hosting K-pop concerts, it’s that there will always be a turnout, big or small. Ads and engagement provide the revenue they would need. Additionally, virtual concerts viewed in portrait mode don’t give much room for a fancy stage or effects, allowing concerts to be held on a much smaller budget.

As K-pop becomes more global, and as the world shifts to more non-contact platforms, be it for K-pop consumption or not, it wouldn’t be surprising to see TikTok become an increasingly powerful tool in promoting K-pop. Conversely, as K-pop continues to evolve, TikTok is likely to progressively realise the purchasing and consumption power that comes with K-pop trends and fans. This symbiotic relationship creates much opportunity for both the TikTok creator and TikTok consumer, and we can only imagine where the possibilities will take us in the future.

(YouTube: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5], TikTok: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7]. Business Insider. Tech Radar. Rolling Stones. Teen Vogue. Images via: TikTok, Hybe Entertainment, SM Entertainment.)