On January 31, 2013, weekly Japanese tabloid Shukan Bunshun featured pictures of AKB48 member Minegishi Minami leaving the apartment of Generations member Shirahama Alan. Almost immediately AKB48’s management announced that they would be demoting Minami, one of the few remaining original members of the sprawling girl group. Minami is now relegated to trainee (kenkyuusei) status, stripping her of most opportunities for performance and press. (Shirahama’s agency, by contrast, released a press release stating “We leave his private life up to him,” and plan to pursue no punitive action.)

On January 31, 2013, weekly Japanese tabloid Shukan Bunshun featured pictures of AKB48 member Minegishi Minami leaving the apartment of Generations member Shirahama Alan. Almost immediately AKB48’s management announced that they would be demoting Minami, one of the few remaining original members of the sprawling girl group. Minami is now relegated to trainee (kenkyuusei) status, stripping her of most opportunities for performance and press. (Shirahama’s agency, by contrast, released a press release stating “We leave his private life up to him,” and plan to pursue no punitive action.)

A few hours later, Minami shocked the world by releasing a now-removed YouTube video where she begged her fans for forgiveness…with her head completely shaved. Both Minami and her agency claim that this act of contrition was entirely self-motivated, a point which I am not going to debate with speculation. However, regardless of the impetus behind it, the severity of her decision has fans in Japan and beyond questioning the state of the J-pop idol industry.

Minami’s situation is far from an anomaly. Just 6 months ago, an ex-acquaintance of another AKB48 front girl, Sashihara Rino, approached Shukan Bunshun with nude pictures, earning Sashihara a demotion to lesser known sister-group HKT48. After being caught spending the night at the house of Da Pump member Issa Hentona, Masuda Yuka resigned from the group entirely this November. NMB48, another AKB48 sister group, saw the graduation or resignation of 4 members in 2011 over (never confirmed) scandals.

Minami’s punishment, while extreme, also fits within the J-pop construction of the idol-fan relationship. When idols fail to meet explicit or implicit goals, they frequently impose a punishment on themselves, to demonstrate their undying devotion to their fans. Tamai Shiori, a member of fast-rising idol group Momoiro Clover Z, pledged to her fans that she would cut her hair short in penance if the group’s first album could not reach the #1 spot on Japan’s Oricon Chart. When “Battle and Romance” failed to upset rock duo B’z ‘s “C’mon,” Shiori cut her long hair down to a short bob. In March 2010, the same group’s agency invited fans to a public weigh-in to make sure all members were of ‘Idol Weight’ before their debut. Takagi Reni, the member who fell .8 kg above the cut-off subsequently lost so much weight that fans feared she had developed an eating disorder. When KAT-TUN member Akanashi Jin decided to get married without telling his agency, his concert tour was canceled and he was expected to pay the difference in fees.

Minami’s punishment, while extreme, also fits within the J-pop construction of the idol-fan relationship. When idols fail to meet explicit or implicit goals, they frequently impose a punishment on themselves, to demonstrate their undying devotion to their fans. Tamai Shiori, a member of fast-rising idol group Momoiro Clover Z, pledged to her fans that she would cut her hair short in penance if the group’s first album could not reach the #1 spot on Japan’s Oricon Chart. When “Battle and Romance” failed to upset rock duo B’z ‘s “C’mon,” Shiori cut her long hair down to a short bob. In March 2010, the same group’s agency invited fans to a public weigh-in to make sure all members were of ‘Idol Weight’ before their debut. Takagi Reni, the member who fell .8 kg above the cut-off subsequently lost so much weight that fans feared she had developed an eating disorder. When KAT-TUN member Akanashi Jin decided to get married without telling his agency, his concert tour was canceled and he was expected to pay the difference in fees.

Scandals, of course, occur in music industries around the world. In K-pop there have been scandals about idol contracts, bullying, and car accidents over the past few years, and these have all received as much or more media attention than the average J-pop scandal. The difference, however, lies in the ways in which idols react to the scandals and the types of information that becomes public. The fan-idol relationship, carefully maintained by J-pop agencies, requires idols to appear powerless in the face of fans, and scandals serve to both engage and distance fans.

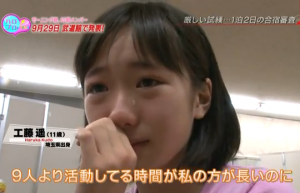

Demographically, K-pop stars tend to be older than their J-pop contemporaries. Though some AKB48 members still perform into their 20s, the average age of the group tends to fluctuate between 16 and 17. Two other major J-pop groups, Morning Musume and S/mileage, have average ages of 16.2 and 15.5 respectively. All these groups keep the average age down by an audition-graduation system that has been in use since Onyanko Club in the 1980s. Most idols debut before they reach 16 and are retired by 24. However, the fan-idol relationship in Japan starts even younger. While agencies in Korea and the West tend to hide their trainees away until they can at least carry a tune and speak on stage without crying, J-pop idols face cameras that capture every false note and frustrated tear from the moment they audition. The trainee system used by Hello!Project, AKB48 and Johnny’s Entertainment (among others) also allow fans to get to know future idols in their raw, nascent stage. In a CNN interview with Anna Coren,  AKB48 producer Yasushi Akimoto affirmed “Usually talented people compete at auditions and those people grow to become stars through a series of hard lessons. When they make their debut, it’s time to show them to the world. But in the case of AKB48, we reveal them prior to that process.” Debuting girl early means that fans become invested not only in the product represented by the polished idol and her releases, but the process of the idol working to fulfill her goals.

AKB48 producer Yasushi Akimoto affirmed “Usually talented people compete at auditions and those people grow to become stars through a series of hard lessons. When they make their debut, it’s time to show them to the world. But in the case of AKB48, we reveal them prior to that process.” Debuting girl early means that fans become invested not only in the product represented by the polished idol and her releases, but the process of the idol working to fulfill her goals.

Japan doesn’t have the reality television that exists in the US. Instead, idol tarento and seasoned comic performers participate in interviews, discuss current events and compete in inane, often painful competitions. While a Western reality television participant may overemphasize a few of her defining traits while on camera, a J-pop idol is expected to embody her particular character both in promotional activities and in everyday life. Of utmost importance is being pure — obeying curfew, not smoking or drinking and abstaining from dating, rules that are written into the contract of most female idols. (Male idols, the vast majority of which are managed by entertainment mogul Johnny’s Entertainment, are marketed under a very different strategy, and rarely face the same constraints). With the rise of cell phone cameras and twitter, more than ever an idol is expected to maintain her purity in all aspects of her life.

Most coverage of Minami’s scandal has dismissed the no-dating rule as a way for idols to remain available sexual fodder for adoring fans. While this is undoubtedly one function of the restriction, it oversimplifies the idol-fan relationship into that typified by porn actors and viewers. Many idol fans are significantly older, and thus view idols both sexually and paternally. Idols dating give agency to the idol that complicates both the fan’s sexual and paternal feelings; the sexual by creating the possibility of affection being actually returned and the paternal by corroding the image of the pure idol.

Most coverage of Minami’s scandal has dismissed the no-dating rule as a way for idols to remain available sexual fodder for adoring fans. While this is undoubtedly one function of the restriction, it oversimplifies the idol-fan relationship into that typified by porn actors and viewers. Many idol fans are significantly older, and thus view idols both sexually and paternally. Idols dating give agency to the idol that complicates both the fan’s sexual and paternal feelings; the sexual by creating the possibility of affection being actually returned and the paternal by corroding the image of the pure idol.

While sexual appeal may spark the fan’s initial interest, ultimately it is the paternal that brings in the most money for agencies. The paternal instinct drives interest in the process of idol development that keeps fans investing in idol success. Supporting an idol is not cheap, and agencies have learned to exploit the idol-fan relationship to maximize their own profits. Key to this relationship is making sure that the idols appear powerless, unable to progress in the system without the help of kind supporters. Thus, in public, agencies aim to exercise complete control over their idols. In reality, however, K-pop stars are more tightly managed by their industries. Most J-Pop stars live at home with their families, attend normal school, and even participate in after-school activities unrelated to their idol training. While J-pop agencies do have a great deal of actual power over their idols’ lives, they appear to exaggerate their actual power in public to make the idol seem powerless. They set difficult obstacles, offer piercing public criticism, and make sure that all the idol’s most powerless moments are captured and distributed on film.

The agencies also actively construct a narrative where the fans who own the most merchandise and buy the most singles are the biggest supporters of the idol, encouraging fans to actively compete to empty their pockets into the agency’s coffers. One of the best examples of this comes from AKB48’s yearly senbatsu election, a contest held to determine the most popular members that will be featured in upcoming releases and promotional activities. By buying a copy of the group’s previous single, idol fans earn one vote in the senbatsu tournament to vote for the idol of his or her choice; multiple copies of the CD mean multiple tickets. The most dedicated fans will spend upwards of a month’s salary to purchase hundreds of copies in support of their oshimen. After months of campaigning, the results are announced with great spectacle on a televised show. There the winners thank their fans and promise to do their best, the losers apologize for letting their supporters down, and the cameras capture every tear and jealous pang for an annual documentary release. (The most recent, “No Flower without Rain” opened in theaters on February 2nd and has already managed over 1 million USD in sales).

Scandals like Minami’s, however show the cracks in the candy-coated reality all idol agencies try to carefully construct. The ensuing shock can cause fans to turn from the idol, focusing their attentions on someone deemed more deserving instead. Of course, for mega-groups like AKB48, there are always dozens of girls with slightly different personalities ready to become a fan’s oshimen, meaning that the agency itself rarely loses money over scandals. Punishment of idols is rarely motivated by the prospect of financial loss, but instead reflects maintenance of order over fan-idol relationships. While scandals frequently ruin an individual member, they keep the idol group in the news and other fans engaged with the spectacle.

Thus, for agencies, most scandals fall under the broader category of spectacle that ends up promoting the group. Agencies actively try to create spectacle to keep fans returning to concerts when the core content varies little. According to an article in The Nikkei Weekly, Japan has been hit hard by the rise of digital media and now depend more on para-release activities than singles and albums themselves. Concert and merchandise earnings accounted for more than 65% of total revenues for management companies in 2011 and probably exceeded 75% in 2012. Big announcements tend to come unexpectedly during concerts, such as the formation of a new group (made from 5/6 former trainees) at the February 3rd Hello! Project concert. Every twist that can keep fans engaged and in attendance is more money for the agency.

Ultimately, the person with the least to gain from this exploitation is the idol herself. Even financially there is little benefit, as idols are hired as fixed salary employees and rarely reap greater profit from greater exposure (There are some notable exceptions in AKB48, however). Legitimately, it’s unclear how much insight into the power dynamics of the idol industry the average trainee has when she joins at 10 or 11. However, painting idols as helpless victims both ignores that the idol is complicit in her decision to sign with an agency, and further reinforces the ‘damsel-in-distress’ narrative that drives profits in the first place. Any change thus has to come from the idols themselves, those deepest within the system. I would argue that within AKB48, there’s growing evidence of this change coming about.

In early 2012, AKB48 sister group SKE48 released a b-side entitled “Koe ga Kasureru Kurai” (Almost until my voice grows hoarse) with a video that depicts the girls as soda choices in a vending machine. The narrative presents a perfect microcosm of the idol-fan relationship: girls beg to be chosen by passing visitors, one girl remains unpopular because she refuses to adapt, then finally changes her mind with the help of an average, everyday guy. The prostitution metaphor is extremely apparent and in viewing it, one is struck by the the bluntness used to deconstruct the idol-fan relationship. Is it tone-deaf exploitation? Pitch-perfect parody? A desperate cry for help? I’ve watched the video dozens of times and I still cannot figure out which.

In early 2012, AKB48 sister group SKE48 released a b-side entitled “Koe ga Kasureru Kurai” (Almost until my voice grows hoarse) with a video that depicts the girls as soda choices in a vending machine. The narrative presents a perfect microcosm of the idol-fan relationship: girls beg to be chosen by passing visitors, one girl remains unpopular because she refuses to adapt, then finally changes her mind with the help of an average, everyday guy. The prostitution metaphor is extremely apparent and in viewing it, one is struck by the the bluntness used to deconstruct the idol-fan relationship. Is it tone-deaf exploitation? Pitch-perfect parody? A desperate cry for help? I’ve watched the video dozens of times and I still cannot figure out which.

Ultimately, I feel the same way about Minegishi Minami. Fans are quick to dismiss Minami’s actions as horrific, contextualizing them within historical contexts ranging from samurais to French spies in Nazi Germany. Minami’s self-imposed punishment seems so outrageous that it is almost performance art, and I want to suggest that maybe that’s the point. By acting in a way that’s ultimately extreme yet consistent with rules governing the idol framework, Minami has both taken control of her own narrative and questioned the dynamics of the idol industry. It’s not a feminist approach, nor is it particularly liberating, but it’s catching the attention and the criticism, however misinformed, of a worldwide audience. If Minami wanted to start a revolution — and it isn’t clear she did — she certainly has set the groundwork with her polarizing video.

(Nikkei Weekly, tokyohive.com, wired.com, japan-now.livejournal.com, cnn.com, boxofficemojo.com , http://happyxgoxlucky.wordpress.com/ ani-culture.net)