So much time, energy, and ink (proverbial or otherwise) is spent covering the Korean Wave, also known as Hallyu. K-pop enthusiasts are quick to report the effects of Hallyu in nearly every nook and cranny of the globe, and some have gone as far as to declare that K-pop is South Korea’s newest “soft power” tool. However, with all of the flash mobs and overhyped local accolades that K-pop has earned for itself outside of both South Korea and Asia, many forget that K-pop’s far-reaching influence can sometimes have an effect of much greater consequence. The latest people to benefit from Hallyu? None other than the citizens of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, more commonly known to us as North Korea.

So much time, energy, and ink (proverbial or otherwise) is spent covering the Korean Wave, also known as Hallyu. K-pop enthusiasts are quick to report the effects of Hallyu in nearly every nook and cranny of the globe, and some have gone as far as to declare that K-pop is South Korea’s newest “soft power” tool. However, with all of the flash mobs and overhyped local accolades that K-pop has earned for itself outside of both South Korea and Asia, many forget that K-pop’s far-reaching influence can sometimes have an effect of much greater consequence. The latest people to benefit from Hallyu? None other than the citizens of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, more commonly known to us as North Korea.

Just about a year ago, the Korea Institute for National Unification published a book called Hallyu, Shaking North Korea — and as the name implies, it outlines the various ways in which Hallyu is having some serious  implications on the decisions of many North Korean citizens to defect with the ultimate goal of arriving in South Korea. Essentially, North Korea is no longer an airtight authoritarian regime whose citizens’ exposure to the world around them comes exclusively from official government publications; smuggling and illegal cross-border trade operations with China have introduced South Korean movies and drama DVDs to the northern half of the peninsula, while (illegal) construction of satellites for state-issued televisions (which are normally programmed to receive only official state channels) has produced access to South Korean channels and news programs. Exposure to South Korean programming — particularly dramas that are intended to portray daily South Korean life (okay, so they’re a little exaggerated, but you get the general idea) — are starting to overturn the official government narrative about South Korea. North Koreans are beginning to realize that, contrary to popular belief, South Koreans are not miserable, wretched slaves who have for decades suffered under the thumb of the imperialist American bastards; rather, they are people who eat white rice on a daily basis and enjoy private ownership of automobiles, among other things. They are people who enjoy freedom.

implications on the decisions of many North Korean citizens to defect with the ultimate goal of arriving in South Korea. Essentially, North Korea is no longer an airtight authoritarian regime whose citizens’ exposure to the world around them comes exclusively from official government publications; smuggling and illegal cross-border trade operations with China have introduced South Korean movies and drama DVDs to the northern half of the peninsula, while (illegal) construction of satellites for state-issued televisions (which are normally programmed to receive only official state channels) has produced access to South Korean channels and news programs. Exposure to South Korean programming — particularly dramas that are intended to portray daily South Korean life (okay, so they’re a little exaggerated, but you get the general idea) — are starting to overturn the official government narrative about South Korea. North Koreans are beginning to realize that, contrary to popular belief, South Koreans are not miserable, wretched slaves who have for decades suffered under the thumb of the imperialist American bastards; rather, they are people who eat white rice on a daily basis and enjoy private ownership of automobiles, among other things. They are people who enjoy freedom.

It wouldn’t do well to overstate the impact of Hallyu on North Koreans’ decision to defect, but it is important to recognize that social media can and does have a noticeable impact on an individual’s perceptions. One defector identified as Mrs. Song (whose story can be read in full in Barbara Demick’s Nothing to Envy) admitted that watching Korean dramas and the televised 2002 South Korea-Japan World Cup during a stay in China ultimately pushed her to defect to South Korea; seeing South Korean citizens — Koreans, just like her — reveling in a city of modernity, a city of freedom, led her to the understanding that life could be better. The Korea Herald echoes this, reporting that 41% of 33 defectors interviewed said that they had watched Korean programming once or twice a month, with a third of these defectors reporting that they had watched Korean programming on a daily basis.

The Korean Defense Ministry, too, has realized that Hallyu might hold more power than do guns and artillery. In 2010, they proposed using girl groups such as SNSD, After School, KARA, Wonder Girls, and 4Minute in a psychological warfare campaign that would broadcast music videos and songs across the DMZ with the goal of influencing North Korean soldiers stationed there. Though a generalization, North Korea is, on the whole, far more conservative (at least officially) than is South Korea, and it is thought that the provocative outfits, colors, and overall style of girl groups would have a significant impact on the conscripted young soldiers (North Korean soldiers serve for about ten years — a huge chunk of their youth and much more time than their South Korean counterparts are asked to give to their country).

The Korean Defense Ministry, too, has realized that Hallyu might hold more power than do guns and artillery. In 2010, they proposed using girl groups such as SNSD, After School, KARA, Wonder Girls, and 4Minute in a psychological warfare campaign that would broadcast music videos and songs across the DMZ with the goal of influencing North Korean soldiers stationed there. Though a generalization, North Korea is, on the whole, far more conservative (at least officially) than is South Korea, and it is thought that the provocative outfits, colors, and overall style of girl groups would have a significant impact on the conscripted young soldiers (North Korean soldiers serve for about ten years — a huge chunk of their youth and much more time than their South Korean counterparts are asked to give to their country).

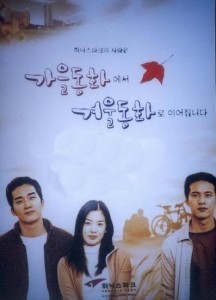

Given recent defector testimony and the ever-changing penetrability of North Korea, it is likely that South Korea will continue to devise new strategies by which to make use of Hallyu in reaching out to North Koreans. Targeting a new, up-and-coming young generation who have grown up in a less sheltered world than did their parents would likely be a worthwhile investment. As a starting point, they can keep in mind that the defectors’ most favored drama was the the 2000 hit Autumn Fairy Tale starring Won Bin and Moon Geun-young. Who better to inspire dreams of freedom?

(One Korea, The Korea Herald, Chosun Ilbo English Edition, Barbara Demick, Nothing to Envy (New York: Speigel & Grau, 2010))